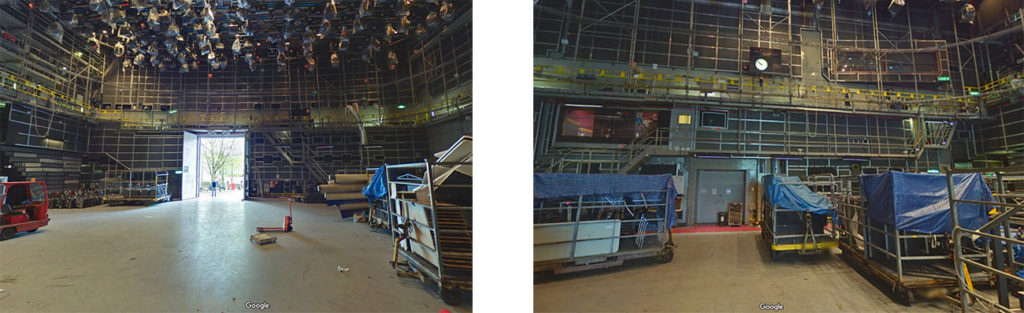

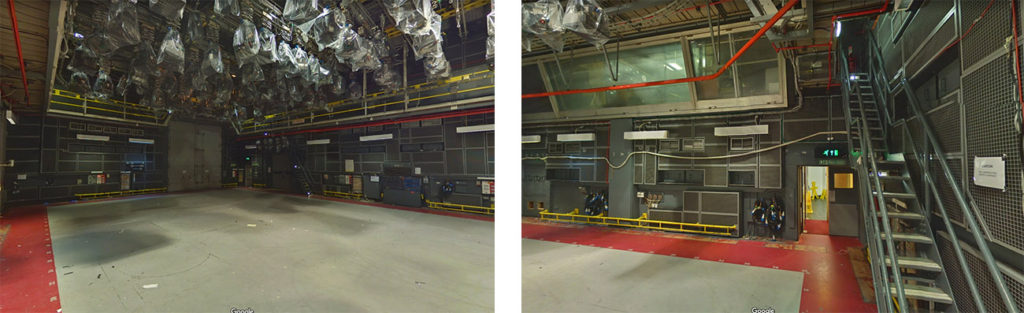

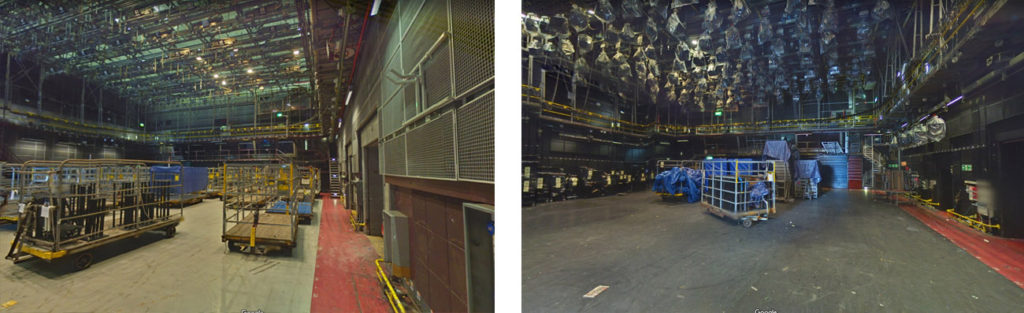

David Newbitt drew attention to a 2013 Google tour of Television Centre, before an incompetent management sold it off.

Go here – https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@51.5099449,-0.2265976,18.5z?hl=en-GB for the tour, they’re the fainter lines inside the building.

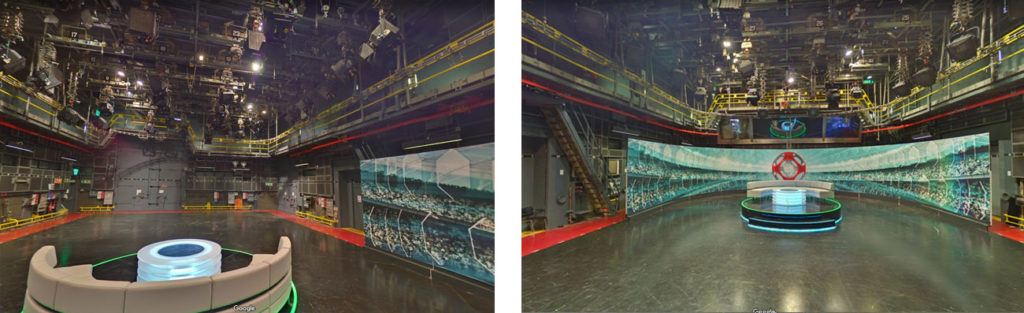

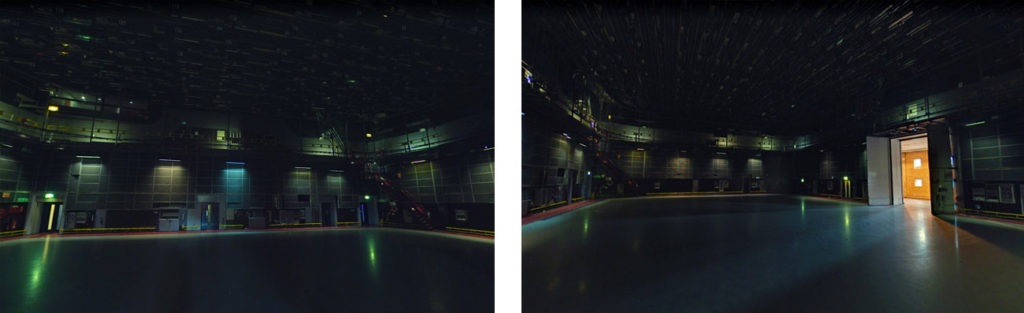

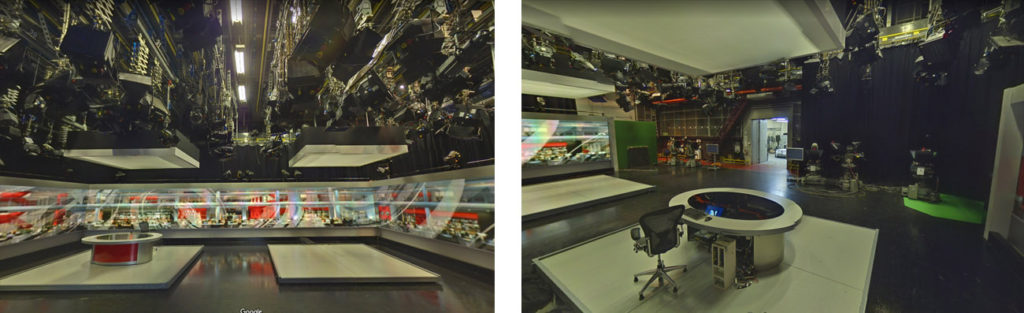

I’ve done the tour and lifted some stills. Underneath each set of studio pics are stories related to that particular studio

Links – TC2 TC3 TC4 TC5 TC6 TC7 TC8

TC1

David Newbitt: One of the joys of life on a sound crew was the occasional requirement for flying the boom/s. If you were lucky, a cable run from the gantry via a convenient scene hoist was all that was required. Sometimes of course it required a drop all the way down from the grid. We all got quite adept at judging where the cable would hit the floor – sort of variation of parallax error so familiar to us boom operators. In TC1 of course this was a fair climb but how fascinating it was looking down from this height at the spectacle of such a vast studio and all its technical magic. That aside there was, for a time at least, another diversion:- In the far corner of the grid at the ring road end was a short extra run of steel steps leading to an emergency exit. At some point this notice had been fixed to the door – “IN CASE OF FIRE, KEY IS AVAILABLE FROM RECEPTION”. Don’t know how long it stayed there but, safety implications aside, it was amusing.

Roger Bunce: My primary memories of TC1 concern the epic scale of the productions mounted there.

In 1965, as a very junior Trainee, I was cable-bashing on Buddy Bregman’s musical spectacular, “Songs of the American Civil War”. The whole studio floor was converted into a stylised battlefield, with reconstructions of historical events, including the execution of John Brown (cue the song). The following year, when I was still a trainee, there was more spectacle with Benjamin Britain’s opera “Billy Budd”. The entire studio was filled with a life-sized Napoleonic man-of-war, with masts and rigging extending high into the lighting grid. Our largest camera crane looked like a toy beside it. Bill Jenkin and I found ourselves singing sea shanties as we coiled up camera cables, pretending we were jolly Jack Tars coiling ropes. I have dim memories of other spectaculars of the time, including a dramatic ballet, called “Corporal Jan” (1968), and a dark, dry-ice shrouded Opera called “The Mines of Sulphur” In 1969/70, “Doctor Who” converted TC1 into a vast, subterranean cavern, with an impressive array of stalactites and stalagmites. It was inhabited by the reptiloid Silurians, who, with a red flashing light on their foreheads and large, flat, rectangular ears, were probably the most ludicrous-looking species ever to confront the Doctor. Their guard-dog was a therapod dinosaur: a nine-foot-tall latex creation, inhabited by a small, bald, white-whiskered man named Bertram, who wore ballet pumps and tights.

Also, in 1970, fictional cops had a close encounter with real-life robbers. We were working in Studio One and I had a Trainee attached to me (who prefers to remain anonymous). He was a smoker, and finding himself underemployed on a particular scene, he went into Tech. Stores for a smoke. Whilst there, he heard loud and disturbing noises coming from outside. Leaving the Stores via the back door, he went to investigate. In those days, the Cashiers, where BBC Staff collected their pay packets, cashed their expenses, etc., was located nearby. Advancing along the corridor, my Trainee found himself confronted by a large man, wearing a stocking over his face and holding a pick-axe handle. Their eyes met (as well as eyes can meet through a stocking). My friend reversed back into Tech. Stores. The first person he told was an Electrician, who immediately reached for the phone. “Are you calling the Police?” “No! The Sun. They’ll pay a few quid for this!” My Trainee spread the news to everyone he could think of but, by the time the authorities had mobilised, the robbers had made their escape. Ironically, the programme we were working on was “Z Cars”: a studio full of policemen, but no one who could actually arrest anyone. My former Trainee still prefers to remain anonymous. He reasons that, somewhere out there, there may be an eighty-year-old bank robber, who might remember him.

The drama serial “The Girls of Slender Means” (1974) was completed in TC1. The larger studio was needed to stage some of the more dramatic effects sequences. With the aid of smoke guns; multiple bendy gas jets, and dollops of inflammable gel, the Special Effects team converted the main, two-storey set into a blazing inferno: complete with falling roof timbers. The heat was intense, and the EMI 2001 cameras could barely cope with the brilliance of the flames. Normally such a scene would have been shot on film, well away from human habitation. It is unlikely that today’s Health and Safety ethos would permit such a major fire in a studio centre. The following year, in an episode of “Churchill’s People” called “The Coming of the Cross”, Studio One managed to accommodate both the interior of Whitby Abbey and an entire Anglo-Saxon battlefield. The 1977 drama “Danton Death”, directed by Alan Clarke, re-enacted the French Revolution, in front of stylised scenery. TC1, surrounded by a white cyc, became La Place de la Révolution, with large crowds of costumed extras cheering the rise and fall of Madame Guillotine. On another occasion, I remember TC1 being converted into a zoo, for a single music number. The studio was filled with all manner of exotic live animals, and Ken Dodd, dressed as Dr. Dolittle, wandered amongst them, singing “Talk to the Animals”. At one point, an elephant swung its trunk and walloped him somewhere uncomfortable. (I think that incident appeared on a Christmas tape.) De-rigging cables, after the studio has been full of animals, is never a pleasant experience. “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” (1981) also used TCI for its more monumental scenes. The interior of the Vogon spaceship used scenery recycled from the film “Alien”, but the cavernous wide shot of the hold was augmented using an old filmic technique: some of the peripheral scenery was painted on a sheet of glass, placed in front of the camera. Later in the series, similar wide shots (e.g. the infinitely-improbable vision of Southend Pier) were created using overlay. However, the vast interior of the Restaurant at the End of the Universe was full-size solid scenery.

Despite being a relatively low-budget Children’s Programme, “Blue Peter” often used Studio One. In the days before ‘Producer Choice’, when Producers could genuinely choose things, Biddy Baxter was very effective at getting the studio she wanted for her programme. On at least two occasions, I was working on “Blue Peter” in TC1 when those massive, three-storey-high, scene-dock doors swung open, and a double-decker bus was driven into the studio. For one of these I was on the front of the Mole, at maximum height, tracking back in front of the bus as it entered. On air, the driver wildly overshot his intended end position. Fortunately, my tracker had the wit to overshoot his marks, in compensation, and the shot was held, but we came perilously close to running out of studio. On the other occasion, a bus had been fitted out as a mobile medical centre, for use overseas. I was providing a hand-held tour of the interior. My first shot was a wobbly-vision look at the upper deck; followed by a wobbly walk backwards down the stairs; then a wobbly look at the lower deck, and a wobbly step backwards onto the studio floor. After the briefest of cutaways, my second shot was a straight walk backwards to show the whole bus. On the live transmission, the first shot worked reasonably well. On the second shot, I took my first step backwards, when the Blue Peter dog (was it Goldie?) decided to amble between my legs. I tripped. The dog hastily retreated, in the same direction I was trying to walk, tripping me at every step. Against all the laws of physics, I swear that the camera continued moving back, in a straight line, despite the fact that I was completely off balance. My feet were no longer under my centre-of-gravity. They were making only fleeting contact with the floor, as they flailed about, trying to find any surface which wasn’t covered in fur and didn’t yelp when I stood on it! Each year “Blue Peter”’s Christmas edition came from TC1, and always ended with a spectacular display of marching bands and choirs singing Christmas carols. Meanwhile, the regular Camera Crew brought in tinsel, fairy-lights, etc. for our annual ‘Decorate a Camera’ competition. The Production team awarded a bottle of champagne to the winner. My entry, one year, included a cardboard head of Rudolf the Reindeer, with the camera cue light as his red nose.

After a refurbishment, some new wall boxes were fitted in TC1, behind the audience rostrum. They had a design flaw. The tying-off bars were too close to the box, such that it was impossible to pass a 13-amp plug through the gap. Confronted with this problem, for the first time, and in a hurry to plug-up a monitor, I improvised: passing a loop of wire behind the bar, and then threading the plug through the loop. It wasn’t the regulation clove-hitch, but it seemed to do the job. I forgot about it until the derig, when I found half the crew gathered around that wall box, totally baffled by my knot. They were unable to untie it, and were convincing themselves that it was impossible to have tied such a knot in the first place – without disconnecting the plug and reattaching it. Given this rare opportunity to show off, I brushed them aside and effortlessly demonstrated my superior understanding of topology.

Chris Eames: In July 1963 I was on crew 11, with Colin Reid as Senior Cameraman. TC 1 had only just opened, and the crew had the series of ‘Best of both Worlds’, specifically designed, I think to show of the large studio, with a full orchestra and celebrated conductors. It used the Chapman Crane – much too big, even for that studio. The first show with the crew I duly cable bashed. The following week, I was due to do the same task, however a pool cameraman, Colin Widgery, if I remember correctly, was sick, and as I was the only spare body, I seem to remember Colin saying to me, “I think you will have to do Camera 3, I hope I am not throwing you in at the deep end”. Camera 3 was the conductor’s camera, complete with Autocue for the conductor, in this case Nelson Riddle, to introduce the next item. It only had about 6 shots in the entire programme. The catch was that each ending shot on an item was usually a high wide shot on the crane, cut to me on a tighter shot just out of his shot, then fast track in, on shot, to get close enough for the man to read his next link. I think that the longest track I had done in my previous 3 months on cameras was about 3 feet! The show was, of course live, the director was Brian Sears, not a sympathetic director, oh, and the ped was a tiller device, not a ring steer. I’m afraid that the show was a blur, I didn’t get shouted at, so I can’t have been too bad, but as a baptism of fire for a 19 year old, it left a lasting memory.

Roger Bunce (again): In 1981, TC1 was encircled with blue cycs (see Overlay Epics) for “David Bellamy’s Back-Yard Safari’, in which the miniaturised zoologist had encounters with earthworms and insects. The mini-beasts had been shot by Oxford Scientific Films, and the studio output had to be ‘film-looked’ to match. Our extremely imaginative Director, Paul Kriwaczek, was experimenting with a number of new techniques and devices. Some of his inventions had a pleasingly Heath-Robinson quality, e.g. a caption stand attached to a telescopic panning handle. This is the first and only time that I have mastered a double-sided-rotating-mirror shot (even if I had to run upstairs and ask the Paul to stop directing, while I sorted it out!) And it was the first time that the whole Camera Crew were given a credit, both on screen and in the book of the series. It was followed by a sequel, “David Bellamy’s Seaside Safari” in 1985 “Alice in Wonderland” (1985) was also shot in Studio One against a blue cyc, which meant that Alice had to wear an unfamiliar yellow dress. Some of the backgrounds were derived, in the conventional manner, from 2-D graphics, but most used exquisitely detailed twelfth-scale models, which had been created by BBC Special Effect Department. The Director, Barry Letts, had developed a new means of matching perspective. He had made two cube-shaped frames. One was six feet tall; the other was six inches. The six-foot cube was placed in the live-action area, in front of blue, and a six-inch cube to be placed in the model. Provided the cameras could match the two cubes, everything else should look right. Barry was constantly on the studio floor, making arithmetic calculations before each shot. He would regularly call to the Cameraman, “What lens angle are you on?” The truthful answer would have been, “I’m not sure.” But the necessary answer, on this occasion, was a quick and confident, “Thirty-Five Degrees!”. O.K. we had no way of being certain, but any hesitation, or attempt at honestly, was likely to cause delay and confusion. As all Cameramen know, lens angle does not affect perspective! Some of my favourite overlay productions came from the imaginations of Ian Keill and Andrew Gosling: a uniquely inventive production team. With TC1 and a blue cyc, they created a range of completely original and often fantastical programmes. Memorably, they brought ’Jane’, the saucy wartime comic strip, to life, in two daily serials: “Jane at War” (1982) and “Jane in the Desert” (1984). Most of their projects were humorous, but “The Ghost Downstairs” (1982) was a dark, sinister tale, set in fog-bound Victorian London. A dodgy lawyer sells his soul, believing that he can evade the consequences by inserting artfully ambiguous smallprint into the contract. But the purchaser is not the Devil – It’s the other one! – and the lawyer’s own deviousness leads to his doom. The weird storyline was complimented by equally weird, surreal visuals. Those distorted, dreamlike images must be some of the strangest pictures I’ve ever helped to compose. My last project with Ian and Andrew was “Pyrates”: a rollicking, swashbuckling saga of buccaneers and buxom wenches (and buxom buccaneers); which voyaged from 17th Century London, to the Spanish Main, via desert islands and battling brigantines, without leaving TC1 – and the wide blue sea was a wide blue cyc. There was swinging on ropes; walking on planks; cutlasses clenched in teeth; mutinies, maroonings, treasure chests and even a giant octopus. Here I learned that if you have a problem with an actor underplaying, it can be instantly cured by dressing him as a pirate! This was probably the most prolonged period I had spent entirely surrounded by primary blue. After working a 12-hour day, your eyes became accustomed to the colour imbalance, but when you stepped outside, the world seemed to have turned a strange shade of orange! Also, after spending a week or more staring at pictures, trying to make the perspective look convincing, when you finally escape, you find yourself doubting the perspective of reality!

And it was on the floor of TC1 that I had my epiphany – my moment of revelation – when suddenly I understood, with great clarity, the nature of my workaday existence. To set the scene . . . It is Thursday, 7th September 1995. I am lying on a mattress. Beside me lies a charming young lady wearing short shorts. It’s all perfectly respectable. We are on the floor of Studio One, at Television Centre. We are exhausted to the point of collapse. The rest of the Camera Crew, equally exhausted, lie collapsed on other mattresses nearby. All around us, between us and beneath us, the studio floor is splattered with copious puddles of green, purple and orange slime. Just in case the reason for this isn’t immediately obvious . . . I will explain. We are working on a series called ‘Run the Risk’. It is a children’s games show. The contestants are racing around a complex, elevated obstacle course. Below them are large tanks full of colourful slime, into which they are in danger of plunging. Overhead are dump-tanks, full of similar slime, threatening to drench them from above. As the Children race, the Camera Crew race with them, up and down stairs, along perilous gantries, following their every move. By the end of the game, the Children are breathless and exhausted. So, are the Camera Crew. The Children collect their prizes, and go home for was well-earned rest. The Camera Crew set up for the next show, when they will have to do it all again. We have been doing four or five shows each day, for a fortnight. We are now beyond exhaustion. We are physically and mentally shattered. We no longer know what day it is, or what planet we are on. We can barely stand upright. Fortunately, there are a number of mattresses scattered around the studio floor. They are crash-mats, positioned to catch any child who falls off the race track. At the end of each game, I attempt to position my camera immediately in front of one of these mattresses. Then, when there is a break for a reset and tidy-up, I can simply topple backwards – crash – onto the crash-mat – and lie there, brain empty, until I am called to start again. So, this is how I come to be lying, semi-conscious on a mattress, beside a charming young lady in short shorts; in the middle of Studio One; surrounded by puddles of colourful slime. But the Camera Crew are are not entirely inactive. What we are doing is – sipping champagne from BBC paper cups . . . This, too, may need some explanation. My charming companion, wearing short shorts, is a talented baker. Whenever we do a series, she bakes a cake, for the cast and crew. This time her cake is a particular masterpiece: an edible, scale replica of the ‘Run the Risk’ set, including its three pyramids and central volcano. The Presenter, Peter Simon, is so impressed that he has bought the Crew a bottle of champagne. So, this is how I come to be lying, semi-conscious on a mattress, beside a charming young lady in short shorts; in the middle of TC1; surrounded by puddles of slime; sipping champagne out of a BBC paper cup. Oh, and there’s one other thing I should mention. Bombs are falling all around us. Not high-explosive bombs, obviously! These are water bombs, plummeting from the darkness high above and bursting on the floor, with a repetitive – “Whee – Splat” – “Whee – Splosh”. Yet another explanation may be needed. The Visual Effects Crew are working overhead. They have been refilling the dump-tanks with slime. Less physically exhausted than the Camera Crew, but equally brain-damaged, they are now amusing themselves by throwing water bombs at one another. But, since gravity tends to act downwards, most of the bombs are missing their targets and tumbling towards the studio floor, where the Camera Crew lie collapsed. We are taking no notice of this aerial bombardment. We have learned to ignore such things. But then I am splashed by a near miss, and I hear myself saying, in my best upper-class-twit accent, “I say. Careful Old Bean. That nearly went in my cham-pine!” Then I get the giggles, because it is at that moment that it came to me – The Revelation. It dawned like a shaft of clear light, penetrating my dark and fuddled brain. Suddenly, I realised . . . This is what I do for a living! This is my ‘Day at the Office’: my equivalent of the humdrum, nine-to-five, daily grind! And someone is actually paying me to do it! Over the past 30 years, the sheer bonkers absurdity of my working life has crept up on me so slowly, so incrementally, that it is not until I find myself lying semi-conscious on a mattress; beside a charming young lady in short shorts; in the middle of TC1; surrounded by puddles of purple, green and orange slime; sipping champagne from a BBC paper cup; ignoring the water bombs that are bursting all around, that it suddenly dawns on me . . . It’s a funny way to earn a crust!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

TC2

Alec Bray: It’s the mid 1960s – and TC2 hosts “Juke Box Jury” on alternate Saturdays: one show is live, the other prerecorded for the following week. Later, the studio is used for “That Was The Week That Was”. Both shows are un- or under-rehearsed. On JBJ, the cameramen offered shots of the audience for the director to pick: some were lovely shots, as for example two boys, one behind the other,swaying in time to the music, with the cameraman focussing on each one as they swayed into view… On TW3, the script was changing almost moment by moment, so although some of the sketches were rehearsed, there was always an element of jeopardy about the whole production. Further, the whole script could not be contained on one roller of the AutoCue (AutoCue, not Telepromt!) and so each camera’s AutoCue roller had to be swapped out halfway through the programme.

Another show done in TC2 was the twice weekly soap opera “Compact”. Sets ranged down the two long sides of the studio, with the cameras and mic booms set down the middle between the sets. Live, wasn’t it? The last shot of the last programme was of Carmen Silvera packing up her bag …

Then “Top Of The Pops” moved down from Manchester, and landed in TC2 (until the Musician’s Union insisted on live music and the show then moved into Studio G, Lime Grove – a bigger studio). Sonny and Cher’s first performance on British Television was “I’ve Got You Babe” from TC2 – after a half-hour row with the director, whose parting line was “You are in the UK now, and in the UK the director calls the shots”.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

TC3

Pat Heigham: A big music show in 1967, a version of The Mikado called Titipu, required links between the orchestra in TC3, with the action set in TC4. We had spent the best part of two days setting up the tie lines, via CAR, and were ready to record as soon as we got in on the third day. Horror! None of the linking circuits were there! Overnight, the CAR shift had changed and no-one had thought to gather and label all the double-enders on the jackfield, so the incoming shift had cleared it and broken down all the connections. In TC4 sound gallery, we struggled to remember what had been set up – all the comms lines/talkback/music feeds etc. We managed somehow, and prevented the director from blowing his top, but David Croft was always pretty calm.

TC4

Alec Bray: TC4 monochrome days with the green EMI Image Orthicon cameras – and lots of light.

Michael Bentine always dreamed up something spectacular for the end of each the series of “It’s a Square World”. So, for the – I think – last series in 1964, there was going to be mayhem in a public house.

The basic idea was that a pub was going to explode.During the morning of rehearsal, the props guys came in with boxes and boxes of wax beer bottles. The bottles were to be put on the pub shelves, and behind each bottle was a modified mousetrap (one of the old-fashioned spring type mousetraps) which, when primed with the trap held open by catches which on cue would be fired by a small explosive charge wired back to a control panel.

After some time fiddling with the wax bottles, props and special effects decided that the wax bottles, as produced, were not going to break, as the heat from the studio lighting was softening the wax to the extent that the wax would not and could not crack. So, the props and scene crew set to work and cut large V cuts through the bottles. For each bottle, the point of the V was at the front, and was masked by the beer bottle label. The large gap at the back was supported by a long matchstick. Altogether there were more than three hundred of these bottles.

There were also two large mirrors in the pub set. The mirrors were to be smashed by the scene crew, on cue, hitting bolts on the other side of the scene flats, the big fat bolt heads located between the scene side of the flat and the mirrors.

There were open magnesium flares dotted around towards the audience side of the set, and two large fog machines. In those days, the fog machines were tubes in which there was a heating element onto which was dropped oil, the resultant smoke being blown onto the studio floor by fans mounted at the machine end of the tube. These machines were relative large and unwieldy, and if care was not taken, they would spill oil onto the studio floor (which they did more often than not).

At transmission (recorded as live onto VT), all was set. On the shelves were the three-hundred or so wax bottles, each propped up in position by a matchstick, sitting in front of an explosive detonated sprung mousetrap. Two pristine mirrors behind which were large headed bolts through to the rear of the set. The sparks filled up the open flare boxes, the fog machines started up, and off we went. The flares went off, the fog machines poured smoke into the pub (and dripped oil on the floor), the bottles flew round the set and the mirrors smashed.

And then the director said “retake!”

All the bottles had to be re-assembled, the mousetraps reset and reprimed, the mirrors replaced. All this was done remarkably quickly. The sparks refilled the open flares – but I have a feeling that they wanted to get in on the act, because I am as sure as I can be that they put additional powder into the flare boxes. By now, the studio floor was covered in oil from the fog machines, so it was getting tricky to get the pedestals into position (they were sliding around). So we went for the retake … more fog, more oil, there was certainly more flare from the flare boxes – the cameras could not actually see one another! The bottles smashed, the mirrors smashed – there was smoke and debris everywhere.

If you knew where to look, you could see the scars in TC4 for years following …

Roger Bunce: My first encounter with the ‘Overlay Epic’ came in TC4 in 1974, with “The Great Glass Hive”.

‘Overlay Epics’ were usually spectacular and visually imaginative productions. Actors performed in an apparently empty studio, against a plain blue backcloth. The scenery, which would appear behind them on screen, was generated from other sources: artwork, photos, scale miniatures or pre-recorded locations. The foreground actors were combined with the background scenery using Colour Separation Overlay, or C.S.O. (known outside the BBC as Chromakey, Blue-Screen, Green-Screen, etc.) Studio One, with its size and height allowed vast blue cycloramas to be flooded with uniform light, and provided enough space for artists to stand well away from them, to minimise shadowing and reflected colour.

TC5

Alec Bray: In the mid 1960s, TC5 was almost exclusively the studio for Schools’ Programmes. Often the programmes involved captions, which we were expected to enlarge by tracking in. Now, although the Vinten HP pedestals were lovely to work with in general, moving them just a few inches forward whilst keeping frame and focussing on the caption was quite tricky.

Nearly every crew had a Schools Programme somewhere in their schedule, whether thye wer usually light entertainment or heavy drama crews.

Sometimes there was something different – “Captain Pugwash”! Yes, “captain Pugwash” was an animation done “as live” with television cameras. 4 Cranes, craned up tot he maximum and panned down onto large drawing boards with four animators – two at the top and two at the bottom – who manipulated the arm and face card levels.

TC6

Graeme Wall: I remember on working on several light music shows in TC6 with Crew 15 and Ian Gibb. I was the resident Nike swinger at the time. We did a series wih a singer, who’s name escapes me, which involved a massive set with the Nike running round the outside. On one occasion we had a fast track along the long wall and as we got to the end realised we were being chased by a BBC fireman with an extiguisher in his hand and smoke coming out from under the swinger’s platform. A couple of pages of script had slipped down onto the charger and had caught alight. Had great difficulty persuading the fireman that discharging a water extinguisher onto mains electrics wasn’t a good idea.

On a Black and White Minstrels I did the equivalent of hitting my funnybone in my knee trying to stop the bucket on a sideways move. The TM2 got the nurse to come down to look at it in the make-up room. Obviously it involved me taking my trousers off and I never realised so many make-up girls “worked” on that show and all had to come into the room during the procedings.

TC7

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

TC8

Paul Thackray: Having gone home leaving a ‘Flying by Wire’ contractor building a winching mechanism for a large box (to be flown full of children) as part of a Paul Daniels Magic trick, I arrived at next morning at 0700 to find the contractor sat looking worried. “How is it going?” I asked. He said “I finished about 0600 , filled it with stage weights to simulate the children , winched it off the floor and went to up to the grid. I’d bent all the yellow beams in the roof out of shape.” “What did you do then?” I asked. The reply was “I went to breakfast”. It was going to be a long day!

Bernard Newnham: For The Violent Universe they blacked up one end of TC8, including the roof, and hung small lights down to match the local stars. I was either tracking or swinging the Nike with Peter Ward on the front. We crabbed around Magnus Magnusson to see the constellations, then past him to show that they only work if you are here on Earth, as the stars’ distances are very different. You can see a version of this on YouTube, but Carl Sagan is doing the Magnusson bit.