Developing camerawork, sound perspective, live or “as-live” transmission: here is a glimpse of what Technical Operations were like in those days before digital cameras, CGI and CSO (Colour Separation Overlay), personal mics, weeks of post-production…

This page reports some contributions for Tim Heath (University of Southampton) as part of the ADAPT project by BBC “Technical Operators”, “Technical Assistants” and other people who operated technical equipment. The ADAPT project (2013-2018) was funded by an advanced grant from the European Research Council (grant no. 323626) and based in the Department of Media Arts at Royal Holloway, University of London. The ADAPT Research Team researched the history of British broadcast television technology between 1960 and the near-present. Former television staff were invited to demonstrate the tools and techniques that defined their working lives.

Unfortunately, BBC Technical Operators were under pain of (more or less) instant dismissal if they brought photographic equipment into the studios, so there is relatively little in the way of pictorial evidence. Photographs which exist were either taken by BBC approved photographers (for example on “Top Of The Pops” (TOTP)), taken with the connivance of the programme producer/director, or taken totally against regulations.

Essentially, BBC Technical Operations were the set of technical services, including the equipment and operators needed, to provide the means to transmit live or record television and radio programmes for all BBC television and radio broadcasts. As such, any person or group of persons who “operated” any piece of equipment used in broadcast television or radio are described and their work methods, organisation and management are allowably described here. Vision Mixers were originally part of the Tech Ops crew, but got moved into production. Telecine (always abbreviated in the BBC to “TK”) was operated by technical assistants (on the engineering side of the BBC)(although originally by Technical Operators), and although there were quite a few “who does what” or demarcation disputes within the BBC, studio managers or producers could be found operating equipment.

The term “Tech Ops”, however, is generally taken to refer to the group of people, designated “Technical Operators” or “TOs” by the BBC, who had specific job roles and were responsible for the operation of any of the equipment needed to deliver television pictures and sound, or radio sound, from a suitable location as part of a scheduled or unscheduled programme.

Day-to-day maintenance of the equipment was undertaken by Technical Assistants(TAs) or Engineers.

Telecine (TK)

Author:

Telecine machines were always referred to as “TKx” (e.g. TK1) in the BBC – perhaps so that there would be no confusion with Television Centre Studios, always referred to as “TCx” (e.g TC1).

In the early 1960s, Telecine (TK) was operating from Lime Grove, plus a Mechau at Riverside Studios. Following a big recruitment drive in 1960, there were mainly Technical Operators (TOs) manning the machines. Some recruits had previously been cinema projectionists. TK worked in a two-shift arrangement , working 12 hours a day on Monday, Wednesday, Friday one week, then Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday the next (similar to the AP shift pattern).

It was clearly intended to train all new recruits to a reasonable technical standard. For this they attended a course at the Engineering Training Department at Wood Norton. A few TOs were not so keen to get technical; so there was a short period of high staff turnover. One comedian put a whimsical notice up in the TK control room. ”Yesterday I coudnt evun spel injuneer, now I are one”.

Those who had already attained some technical knowledge were keen to take up this opportunity, so by 1962 all TK operational staff had become technical assistants (TAs) who were then encouraged to progress on to grade C engineer. Two assistant shift supervisors were B1- grade and the supervisor B1. Once one qualified as grade C, by attending another course at ETD, there were frequent opportunities to take on acting B1- grade. This became increasingly relevant as the number of broadcasting hours grew and was a most welcome boost to one’s salary.

At Lime Grove, machines were located in rooms containing either a single 16mm machine or a pair of 35mm for feature film transmission. The ancient Mechaus, although 35mm, were never used for anything other than opening titles or fillers. They were not equipped for film change overs, besides which, the picture quality was noticeably poorer than the EMI or Cintel machines. Each room, or “suite” as referred to now, contained a fairly substantial monitor loudspeaker, a floor-standing 17” monitor, a wall-mounted intercom able to connect to all the studios and Central Apparatus Room (CAR). A video jackfield, also wall mounted, was provided so that the 17” could monitor studio output or other sources. The TK output video was monitored on one of the ubiquitous PYE 14” units.

After reporting for duty on arrival, one would check the daily schedule. This was an A2 sheet on a large clipboard showing each machine assignment. It was the duty of an assistant shift supervisor to allocate each operator to one machine for the day. In the event of a sick operator, some juggling was performed to enable the cover of two machines by one person.

All film material was previewed to check its integrity and note the vision and sound settings. 16mm film was mainly supplied already head-out on spools. Following its preview it would be carefully rewound and returned to its tin to keep it clean and safe. Nitrate stock was not permitted due to its inflammable nature. 35mm film arrived in a tin can, on a plastic centre and tail-out. At Lime Grove it was always in 2k (20 minute) lengths. Spools with de-mountable cheeks were used to enable winding onto a regular spool head-out. It was advisable to verify that the film was wound ‘emulsion side in’. Films having a changeover required both operators so that the cue dots could be verified and their timing mentally noted. After rewinding, the spools were stood on edge in a rack. There could be up to five such reels for a feature film, so it was important to keep them in order. Chinagraph pencils were available for such duties. Any dust would fall on a small area of leader, which was always plenty long enough to protect the images.

Prior to a broadcast, there would be a 30 minute line-up. Initially a check that the TK was appropriately routed, and that video, audio, talkback and cues were all functioning. Cues were usually verbal from the presentation suite, studio director or assistant but there was a buzzer as well. TK worked in a quiet environment, well removed from studio mikes, so headphones were not required. Following those basic checks, the scanner CRT, gate and any accessible lenses were cleaned with a soft lens tissue aided by a solvent called ‘Inhibisol’. The 16mm Cintels were of the polygonal prism type, that had most of the critical optics hermetically sealed, making cleaning very simple. The EMI machines, TK1 and TK2, needed a good deal of painstaking tweaking to achieve optimum performance before the Saturday “match of the day” negative film could be run. For all TKs, a loop of test card C film would be run, to adjust focus, scan geometry and afterglow correction. This loop also carried an optical soundtrack recorded with zero-level 1kHz tone. Video and audio level controls were set and noted. For feature film or film recorded dramas, test card would be run in the pair of 35mm machines simultaneously; making rapid changeovers to get the pictures and sound as near identical as possible. In the Cintels TK3 and TK4, an almost imperceptible switch could be achieved.

The film to be broadcast was now threaded into the mechanism and checked by an assistant supervisor. It would be wound, usually by hand, to the start position on the leader (usually “10” on the leader), so that an 8 second run-up time was available. All interlocked doors were checked so that a clean start was assured. The previously noted video and sound control settings were checked and TK was ready to roll.

Some BBC film productions and film recordings in 16mm were accompanied by a separate 16mm magnetic tape. This was run on Westrex rack-mounted players that had to be brought to a starting point to match the film, then locked into a synchronous system using selsyns. There were a few occasions when locking failed and the Westrex would run independently at a terrifying speed. This tendency had been eliminated by the time the new equipment at Television Centre (TC) was in operation. There was a loop of 1kHz tape to check levels during line-up

Due to a rigorous maintenance schedule, equipment failure on air very rarely happened and performance levels were kept at the highest level possible. TK, VTR and FR (Film Recording) shared electrical and mechanical maintenance workshops for any complex requirements.

TC had a similar number of machines – Cintel except for one Philips – although of later design. They were gathered in two large rooms separated only by their own cabinets. When the 16mm “Lone Ranger” was being previewed, the theme tune carried throughout the whole room. Initially some 35mm machines were not very comfortable to operate due to the picture monitors being set at standing eye level, so one sat on a high stool. It would appear that the planners/installers didn’t understand the requirement for continuous monitoring and fine adjustments as film density variations occurred. When they were replaced by colour machines, the operating position had been greatly improved.

Remote starting of all the TC TKs was now possible. Verbal cues were still used when inserts to studio productions were required; although it was possible for the director to start the TK if he/she wanted.

Broadcasting hours became extended so that the shift pattern had to be slightly altered, bringing in staff at different times. Even so, overtime was often required and a taxi provided for commuting staff after midnight.

With the advent of colour, films were increasingly made in Cinemascope© or similar wide screen format. TK Shift One supervisor was tasked with exploring the means to letterbox, pan and zoom on our new machines. A series of experiments were demonstrated. Zooming was rapidly rejected as the viewing panel reported feeling disorientated. A system of switching vertical formats was settled on. Although panning was now possible it was not used for two main reasons. Firstly it required special training for the operator who now effectively became an unqualified editor. Secondly the movement of the patch on the scanning CRT exposed phosphor areas that had not been brought to operating temperature. This meant that afterglow correction was not optimised and there was a slight change in brightness of the previously unburnt area. (After some hours of use, this burning of the phosphor was visible even when the CRT was not scanning.)

Sound Boom Operation

Author: Tony Crake

1962 HF Transmitters, Skelton, Cumberland:

1966 TVC Sound Crew:

1978 OBs Sound Crew 2002

Many Sound men (a divisive word if ever there was one) will have lots of information. Here is just one little facet of TV Tech Production that may have been ignored.

I started ‘BBC life’ as a trainee engineer in HF Transmitters in 1962. I stayed for 4 years interspersed with many courses and exams at Evesham (Wood Norton Hall, the BBC Engineering Training Department), and then escaped to Television Centre (TVC) in 1966 in answer to a general callto transfer there as a great expansion was taking place!As a total change to the wilds of Cumberland one would say! I thought I might be a cameraman butno! After disastrous attempts to track “Moles” and “Herons”, I and the management thought I would be better suited to Sound and there I stayed. I became a Boom Operator…Now this is a skill which has entirely disappeared. Once upon a time each studio would have had 4 Fisher Booms with operators and a tracker. At this time, VT editing on the 2” Tape system had yet to evolve (what was done was expensive and involved physically cutting the tape).

There was a LIVE “30 Minute Theatre” as I recall, which was done LIVE – believe it or not! Whole scenes were done in “one go”, the only edits were done as planned breaks. There were something like 9 of these allowed per tape, even on long complex dramas!We had to work very close to the actors with a moving coil mic called a D25, no doubt of impeccablequality, but very little “suck”. Quite often a scene would be “split” with two booms overlapping coverage or on big sets even three booms interleaving. The lighting would be a BIG problem. Some of the Lighting Directors (then called TM1 (Technical Manager 1)) had a good grasp of what caused a shadow and others Did Not. Heated arguments would sometime ensue: some were very skilled and others were not! Some would come and discuss it with you or on several rare occasions ask how you would like it “lit”!You could be plagued by actors who could not “hit their marks” though it has to be said the regulars ona Series like “Z Cars” or “Softly Softly” (two other live programmes) would hit them to an inch whilst “Big Stage Names” did not ! Some cameramen could produce highly repeatable shots without effort in terms of framing and headroom, whilst others were totally awry !We had a full script screwed to a metal holder on the top of the Boom “Arm” It was full of detailed scribbled notes by the time we lined up for the final take! Most of the Big Drama programmes took three days in the Studio, finishing with three hours of recording time from 1900-2200. It was really quite intense!

A really BIG Production would be a “4 Day Play” with linked studios. TC1 and TC2, or perhaps TC3 and TC4 for an opera with the Stage in one and the orchestra in another.

Gradually the VT operation became more polished with as many edits as you like. One of the “Softly Softly” directors invented the Recording Pause. A set up for, say, a Wide Angle would be established. VT would run to record, actors would be cued, dialogue cued, and after 15 seconds or so the cameras and booms etc would move into position for the rest of the scene in close up and cross shots or whatever WITHOUT STOPPING THE VT! A lot of the older Engineering Managers could not get their heads round this and would shout “Cameras in Shot …Stop Recording VT!”, to the intense annoyance of said Director: it was now so easy just edit it out rather then stop and start up all the recording gear again.After 12 years I found I had enough of TVC. The studios were becoming empty, the Drama stuff was going elsewhere so no boom operating. So I transferred to OBs for the next 23 years or so but thatis an entirely different story.

Vision control outline

Author: Alec Bray

Whether it was because I had expressed some idea of moving into Engineering (“Racks”) as a Technical Assistant, or whether it was part of the normal rotation, I spent some months in Vision Control as a Vision Operator (started on 25th September 1965). This mean sitting in the Lighting and Vision Control Gallery with the Lighting Supervisor, later TM1 (Technical Manager 1).

In the Television Centre (TVC), the Lighting Gallery was the other side of the Production Gallery to the Sound Gallery, so that the TM1 and Vision Control Operator saw the backs of the production team.

Vision Control (VC) by the Vision Operator was a very useful job, The idea was to make sure that the images from each of the studio cameras matched – and in particular, to make sure that the facial tones from each camera matched. The modern day equivalent is, I believe, the “Colour Timer”, defined as a process which adjusts the final “print” or submission to server so that colours match from shot to shot, regardless of the film stock (or video) and camera used to shoot the scene.

On the “Stagger Through” (nowadays called “blocking” I believe), the VC operator did absolutely nothing. In fact, this was in the Job Description (not simply dossing about). All the controls were put into the middle of their travel at the start of the Stagger, and then left completely alone. The idea was that the senior lighting engineer, Lighting Director (or TM1 as they later became during my time) should light the scene such that the images from each camera matched – a shot from one camera angle was not hopelessly in shadow, for example.

Then, on the first run through, the Vision Control operator could start tweaking the controls a little – but again, the main emphasis was that the lighting engineer should balance the lighting. Most programmes allowed for a stagger and two run throughs, so on the second run through the Vision Control Operator would start to tweak a bit more.

Then came Transmission! The Vision Control Operator had a control for each camera (and the spare) so that was six controls in TC3 and TC4. Each control was on a quadrant, forward and back, which opened or closed the iris on the lens – this iris was driven from a motor mounted in the centre of the lens turret on all the Image Orthicons of the time (Marconi Mk III and Marconi Mk IV, EMI 203 and Pye Mk Vs.). The controls could be rotated – this adjusted the black level. And by pressing on the knob, the picture of that camera was sent to a preview monitor. As all the monitors had slightly different characteristics, this preview monitor was used to “eyeball” the picture match from camera to camera. Anyway, the Vision Control operator had a monitor for each camera, next to which was mounted a vertical oscilloscope on which was displayed a compressed trace of the picture waveform. The idea was that the operator checked the waveform for the black level – black in the picture should be at, or just above, sync level:, and then check for gain – make sure that there was no clipping of the whites in the picture. These controls were very roughly analogous to “brightness” and “contrast” in the picture. Above each quadrant control on the desk was a rotary control for the gamma correction – change the relative amplification of parts of the waveform – stretch the blacks, compress the whites, that sort of thing. The idea was to check the picture for waveform “quality” and then preview the picture on the standard preview monitor to check that the perceived picture quality from camera 1 (let’s say) matched the picture quality from camera 2 (let’s say). Of course, picture quality on the preview monitor was most essential, so part of line up was to put the test image (white and black rectangles – generated by PLUGE!) on the monitors and check the peak white output using a light meter (can’t remember any settings!).

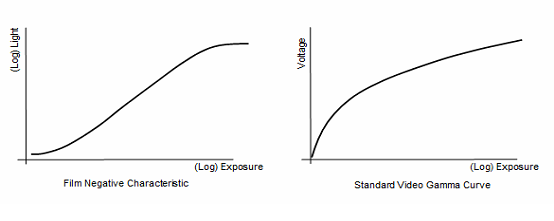

Note at this point that the gamma – the output (here, the electronic waveform) from the camera whose amplitude depended on the light falling on the pickup tube (in other words, the relative differentiation between the shadows, midtones and highlights) – differs for television cameras and for film cameras and film stock.

On the Vision Control desk there were also similar quadrant controls for 2 VT machines and 2 TK machines (although picture matching to a film insert was a losing bet – the gamma characteristics and so on made it just about impossible ever to match Black and White film inserts to the studio pictures. This in spite of the fact that the telecine operators set up the TK machines to a PLUGE during line up – the gamma of the film stock was just different to that of the TV cameras.

So, 6 cameras, 2 VTs, 2 TKs – 10 main quadrant controls each with additional gamma correction control – and two hands, constantly matching outputs.

I used to finish a programme absolutely drenched with sweat, trying to match these disparate sources to make sure that there was no obvious technical difference in picture quality as the Vision Mixer cut the shots.

One day I was on Vision Control in the Theatre (TVT). The Lighting and Vision Control Gallery was located on the Circle, by the Proscenium arch , to the left as you looked at the stage (we never used “Stage Left”, “Stage Right”, “Prompt” or “Off Prompt” in the TVT (in my time) as we viewed everything from the camera viewpoint). Racks were well hidden away in old dressing rooms well behind the rear of the stage.

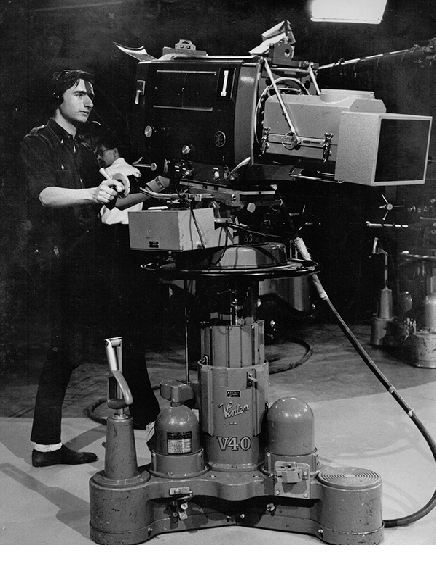

We were on Transmission (I think to VT, but “as live”). I closed the iris a little on the camera to the left of the proscenium arch. This camera was a Pye Mk 5 4.5 inch image orthicon, which was carrying an Angenieux zoom lens in place of the lenses on the turret. (This picture shows the set up, although this is in R1).

The picture quality needed adjusting to match the other cameras – I tried to open up the iris. But nothing happened! This was a music show with a then famous singer – high profile. Gently I tried closing the iris: the picture darkened – but when I tried to open up the iris, nothing happened. Call to racks – but nothing could be done as we were recording.

Every time I touched the iris control, the lens stopped down and would not open up. The performer’s face was gradually darkening on this one camera! I fiddled with the black level and the gamma control to try to get a semblance of normality – but even if I got reasonable facial tones, because of the gamma correction, the background looked wrongly exposed.

Finally we had a break. The engineers (Racks) came out to look at the camera.. The problem was quickly identified: the iris drive motor pinion (cogwheel) in the centre of the lens turret was not engaging correctly with the iris drive on the zoom lens: it was only partially engaging and in one direction only. Remount the zoom lens – and all was fine.

Vision Control had an important part to play when it came to showing captions or animations. The camera would be framed up on a caption, ready, for example, for superimposition over a scene, The camera, as set up normally, would “see” the black card background as well as the white caption itself (a standard caption was a 12 x 9 inch black card with white lettering). Vision Control would have to manipulate the black level (sit down the picture) so that the black background was “below” that standard black level (witch was slightly above top sync level on the waveform monitor).

It was very important to get this right for the animated captions that were used. Many of the animations were produced by Alfred Wurmser (although not exclusively). Because of the complexity of the animations, these were much larger “captions” and often had to be mounted securely.

The lighting had to be correct. So that there were no shadows thrown by the various layers of card as they moved into position (the shadow would give a wrong “reading”. The camera had to be positioned squarely onto the caption, again so that the edges of the animated elements did not throw shadows or were conspicuously visible. Vision control had to sit the picture down so that the black areas were truly black, and then had to adjust the iris so that the whites were at peak level without clipping. The gamma also probably needed manipulation as well to get the grey scale “correct”.

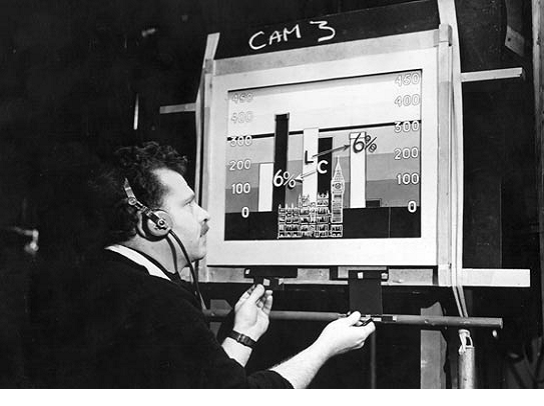

Below is a still from “Late Night Line UP – Z Cars” – see in full below – with an unknown TO working in Vision Control.

Late Night Line Up – Z Cars

“Late Night Line Up” looked behind the scenes at “Z-Cars”. Technical Operations in action!

(use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)