This was instigated by Simon Vaughan, who is the Archivist of the Alexandra Palace Television Society. Simon asked on the tech1 email list –

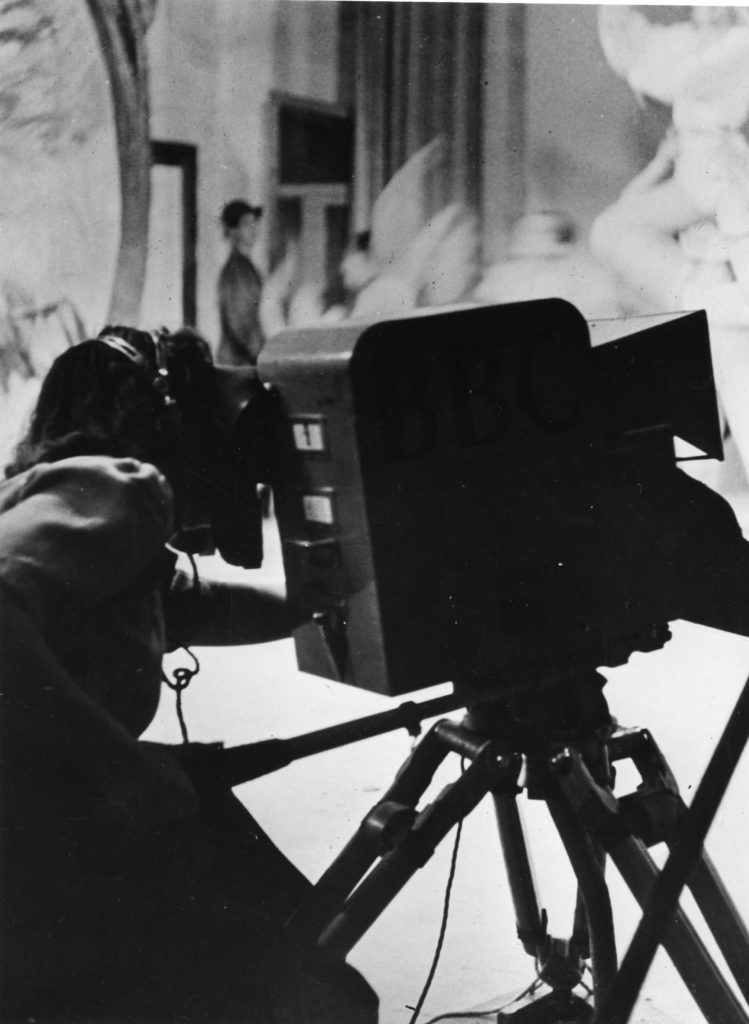

“I wonder if members of Tech-Ops could help in identifying the female floor manager in this photograph. It’s from our Desmond Campbell collection and is from a production of “Coppelia: Act 2” – 30 Jun 1947, featuring The Metropolitan Ballet. The producer was Christian Simpson, design and sets by Stephen Bundy, with Eric Robinson conducted the orchestra.

Any help would be gratefully received.”

A long email thread has followed, with the lady variously identified, including suggestions that she is Joan Marsden, which she definitely isn’t. Eventually Simon found her himself, still alive at 101 in 2021 and living in Australia –

My apologies for not replying sooner to this thread, but I have been waiting for an email from Australia where I have tracked down the lady featured in the photograph I shared a couple of weeks ago.

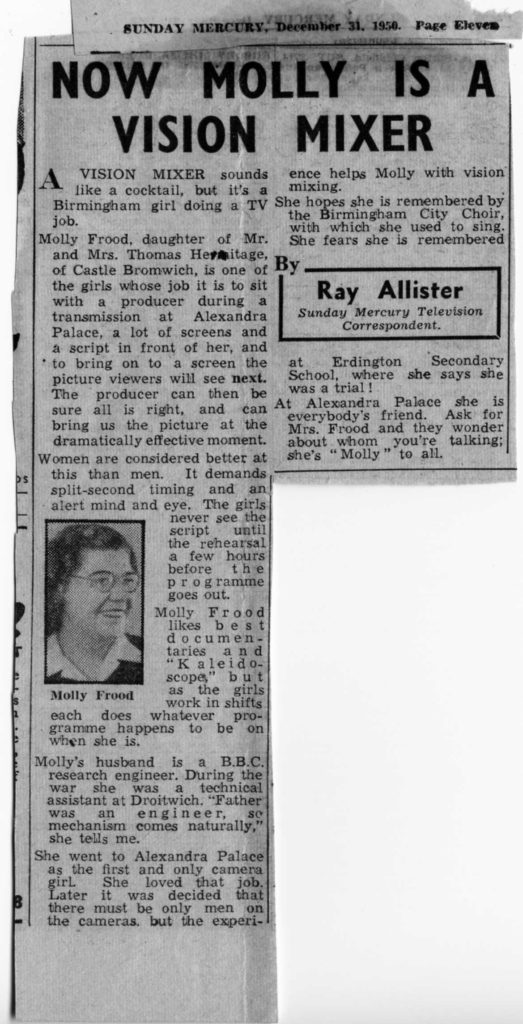

The lady in question is Molly Brownless, (nee Heritage, then Frood), and she was operating the camera in the original photograph! She was at AP from April 1946 and was operating an Emitron on the re-opening day! I’ve been corresponding with Eileen, Molly’s daughter, who was with her the day she received my email – Molly remembers working on the ballet and has a great recall of her days working at AP. Molly is now 101, loving life and is constantly busy. After emigrating to Australia in 1951 she was a pioneer with Australian television when it was established and went on to have an important career within the industry.

Dr Jeannine Baker (who I give total credit for identifying Molly) has recorded a long interview with her, over three consecutive days. Jeannine has recently given a talk to an Australian conference on Molly’s career and it will be featured on a new website for the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. She is also working on a book about women and technology in television covering the UK and Australia.

So, it would appear the first female camera operator was Molly Brownless – she was at AP on re-opening day in June 1946 and was on her camera during the afternoon transmission.

Molly has recorded her memories of AP –

It was the beginning of April when we went to Alexandra Palace. From them on we spent all our time trying to pick up whatever we could from people who were around, who were far too frantic to be doing much about our training. And the girls were looked at somewhat aghast by those who were supposed to be giving what information they could. I suppose we more or less gravitated towards the things that seemed to interest us mostly. Audrey and Joan were happy enough on GRAMS, Isobel hung around Studio B watching whatever was going on in, as well us on the upstairs desk to see what she could pick up there. Rachel was, as far as I remember, from the beginning in Studio A

Before we actually reopened Alexandra Palace, in June 1946, there were seven girls on each shift. First of all, when we started off, everyone was on days, and I didn’t really get to know the people then. Everyone was working, or not working (as the case may be), hanging around the place trying to pick up what information they could. I knew them by name, and you obviously got to know them properly later on when the shifts were changed around and so forth, but all the time I was there, there were just two shifts and we worked alternate days and even when one arranged a shift-swap, one didn’t see the person one swapped with because, well, they weren’t there when you were there – even though you could do that arranging.

The thing I seem to remember that made our life rather tedious at times was operating the switchboard. It was up a little wooden ladder, going out of Maintenance at the back of A RACKS. I think they put us up there to get us out from under their feet. This little switchboard had very little capability – just two lines and Studio A, Studio B, RACKS, and I’ve forgotten who else was on that switchboard, but only a few. If more than two people wanted to be connected at a time, it was not possible. Anyway, we all had to cover it and I seemed to be on it whenever I wasn’t on the camera in the early days. We also covered CCR at times and writing up the Log Book with timings. I think I only did GRAMS about two or three times in all the years I was there. I wasn’t very good at it; I somehow didn’t have the feel for it that some of the girls who came from recording did. I’d been used to dealing with big pieces of equipment at Droitwich. Somehow, I don’t know, those small pieces of equipment didn’t come easily to me. I was fascinated by the cameras right from the beginning.

I remember a chap called George Rose who had been a pre-war vision mixer – when it was all blokes. He was the only one who told any of us anything about vision mixing, as such. Otherwise, we just picked it up by watching whatever went on. When more of the girls came (and I can’t remember how long it was after the service reopened), but it was probably getting on for a year afterwards – we had somebody allocated to telecine. You had to clean all those mirrors on the Mechau projectors – thirty-two, if I remember rightly – (but I am not absolutely certain about that). Occasionally, I remember having to operate the projector in the film unit downstairs. This was where the new telecine was installed when it came, which Gordon Waters took over – that was not long before I left. I occasionally did Sound Floor, you know, shoving in a microphone either above or below on a stand – above or below the camera – but, mostly, I did camerawork to begin with and, of course, that was my delight.

I started on cameras right from the first day – the first day we put out a programme which was the day before the Victory Parade, which was a Friday, and it was the afternoon session in Studio B. I was on Camera 3 (I was mostly on three whichever studio I was in) and so I didn’t, at that time, know very much about Ted Langley who was senior cameraman in Studio A, as Frank Cresswell was the senior camera man in Studio B. The “iron man” was not really moveable except when your camera was not “on air”. You could move the camera around obviously, but it was fairly heavy to move whilst you were actually on air. You could push it with one foot as long as you kept your balance with the other one. But the distance was only a matter of how far your legs would stretch and still keep your balance and keep control.

I was on that “iron man” the day the service reopened. I didn’t realise (in my naïve way), that I was actually going to do the transmission. I’d being doing the rehearsal, but I hadn’t sort of twigged that having done the rehearsal, I would necessarily do the transmission. I thought that all these chaps that were dashing around being very, very, important were going to take over the camera and do it on the transmission and I was absolutely vapped when I found that I was doing it! The next day it was the Outside Broadcast of the Victory Parade, while I was in the studio working on “The Squadronnaires” (featuring Harry Lewis, Dame Vera Lynn’s husband). That was a great time.

Now, lining up cameras – that was a daily chore. Each camera operator took it in turns to line-up their camera, starting with camera 1. I was usually on either camera 3 or 4, so usually it was after morning tea before I got to line up my camera. We pointed the camera at a chart, and it went on from there. RACKS guided you as to what they saw on their screen, and you marked on your glass screen exactly where the picture limits were for that particular camera. You went slightly beyond this limit, so you could see the boom microphone coming in from the top or something coming in from the sides before it got in shot. We also had to watch out for getting a beam from one of the studio lights light in picture – it used to kill the camera. There used to be a burning smell and the camera had to have a new tube.

We used to see a direct picture in the viewfinder. The camera had two lenses, a lens which went straight to the camera and a lens to the side of it which gave the camera operator the same picture but, being a lens, it inverted it – it was upside down and back to front. You quickly learned to look at the picture and quickly balance it and go with the movement in the opposite direction to where you would expect to be going looking at the picture! There was something else we had to worry about too and that was the power lags on the two lenses. The one that went through to the camera was dead straight on, but the one on the side, of course, to keep on the same picture, had to come at a slight angle from the other one so your picture composition might not be exactly the same as the main camera. So, you had to do a little bit of adjustment on that one too.

At the end of transmission, we had to wheel our cameras to the side of the studio and coil up the cables so that the floor of the studio was left clear, ready to build the sets for the next day’s programme. It was a matter of honour that you didn’t leave the place looking a mess. Ted Langley and Ben Blooman were very keen on this, so we had to watch ourselves and make sure everything was just so.

Now it was after Bimbi Harris came and I’d being doing camerawork for quite some time, and she wanted to do that – I’m not surprised, I thoroughly enjoyed it and didn’t see why she wouldn’t want too! One day a reporter came from a television magazine and found out about there being a “cameraman” who was female or maybe he found out about two, I’m not quite sure. Henry Whiting told me that they wanted to do a publicity picture of me on a camera and I was rather tickled at the idea, as you can imagine. I was actually in Studio A the day the reporter arrived – working on a show. At the end of the programme, I tried to find this photographer only to discover that Bimbi had already been photographed on Camera 2, which was the Crab! I can understand why he would have taken her because she would certainly have taken a better picture than I would have done. But, because she was photographed on a tracking camera and because she wasn’t the first female operator, the blokes were a bit peeved. Bimbi hadn’t been at the Palace very long and I had been there for a few years at that point, they didn’t think she should have appeared on the tracking camera which, of course, is not one she would have operated, and they thought it should have been me.

Now the next thing that happened which was why I and Bimbi came off cameras was due to the fact that the camera men wanted to get themselves a higher grade and they were trying to upgrade their pay in relation to the other operators around – it was a very specialised job! All the cameramen, as far as I know, including me, belonged to the Association of Senior Technicians, and they were expecting this Association to back their claim. The Association didn’t like me being one of the camera crew because if I could do it then, obviously, it wasn’t such a very skilled job after all. Henry, to avoid any splitting up of the blokes in the studio I presume, told me that I wouldn’t be able to do camerawork anymore.

I think everybody was a TA1 when went to Alexandra Palace, but I can’t remember it being stated as a requisite. However, when we had been there some time a lot of chaps came out of the Forces, they had not necessarily been in the BBC before the War. The BBC insisted those who were TA1’s would be B Grade. Up until that time, the difference between operators and engineers had been an exam to get the status of B Grade, but they shifted it up a peg to C, so the exam was between D Grade and C, and that was the start of what became qualified “Engineers” as opposed to us “Operators”. We were all still in the Engineering Division, but on different grades. It meant an increase in salary, but not, if I remember correctly very much, and certainly not backdated so it wasn’t quite so startling.

I remember that somebody on the other shift was actually working quite hard to take the exam. Bertie Baker, stated quite categorically that no female, even if they passed the exam, would be given a C Grade job, so we could pass the exam if we wanted too but we would still be B Grade. And so, somewhat to my relief and certainly to the disgust of a number of people, who felt they should have had the same opportunity as the rest did, simmer down. I stayed on B Grade until I left. Well, as you can imagine, I was pretty peeved about that, not just peeved, I was downright sick about the whole thing. I don’t know who told Bimbi, it might have been Henry – but, like me, she just wasn’t rostered on cameras again. Anyway, that was my end of women operating cameras. Henry decided that because I had been so disappointed about coming off cameras – he thought well, okay she can do some vision mixing and I went virtually from the floor on cameras to vision mixing most of the time.

When I got round to Vision Mixing we weren’t able to cut, we were only able to fade up and fade out. A mix was achieved by bringing the fader up onto the first stop, waiting, and then turning it full up whenever we wanted it. Because of the delay on the picture coming up, we couldn’t just bring one in and take one out as quickly as that without a bit of wind-up to begin with! They were beautiful knobs, you know, you grasped them, and they filled your hand – you knew you’d got hold of them. Underneath each fader was a little pushbutton which queued up the next picture that RACKS was supposed to put on the preview channel for us in the Gallery. In those days there were only two screens in the studio galleries – one was the transmitted picture and the one that RACKS put up on preview whichever that happened to be. When you had a quick sequence, you had to yell down to RACKS to be able to bring the preview channel up quickly for you, otherwise, you’d be fading up channels without actually having seen them first!

For gardening programmes when we used to run a cable from Studio A, out over the balcony, down the front of the building and through a channel underneath the road to the garden on the other side of the road where Fred Streeter would do his programme. We were always wondering if there was something he was going to hold that would have to be bought back in the studio. This was always left until the last minute, someone would start taking it back, only to find it was needed back with Fred, and they had to bring it back quickly. I didn’t do the camera work on the gardening programmes, but I did a lot of cable hauling. On those days they used to stop the buses using anywhere in the park. We had to have our badges to get through Alexandra Park and everybody else was kept out except for the buses – but the buses weren’t allowed to stop on their way through.

I remember we were bored a lot of the time, but somehow or other the whole thing seemed to be absolutely joyous. We were all enthusiastic, we were all keen on doing the thing we were doing – we didn’t care what we did particularly, as long as we were involved, and involved we certainly got ourselves!

Molly Brownless – the BBCs first camerawoman, pictured in 2021 when she was 101