Bernie Newnham

I have watched the new version of “Dad’s Army” on Gold – very good. The actors are very well cast, and the directing is true to Croft style original – no silliness. The lighting was much better – sorry to whoever did the original. I missed the 16mm top and tail, but I supposed that would have been a simulation too far.

Barry Austin

The lighting on the original series was mainly by Howard King, with Duncan Brown as well doing a few episodes, both highly respected, award winning lighting men, alas no longer with us. I worked on some of episodes and remember Howard and Duncan very well, both lovely, if slightly eccentric, Duncan especially.

They were both Technical Manager 1s, as at the time, there was no such thing as a Lighting Director in BBC studios, the TM1 did the lighting, but was also responsible for the total technical output of the studio, i.e. he was God !

It is unfair to compare the lighting of 50 years ago to the present day and say it is better now, each is very much of it’s time, it’s like saying the technical output of the camera is better today, of course it is, but what they had at the time is the best there was.

Technical quality is not the be-all: watch episodes of “Fawlty Towers” and cringe at the wobbly sets, boom shadows, flares, dodgy zooms, 16mm film inserts, and yet they are regarded as classics of the TV sitcom. It’s appalling and wouldn’t be tolerated today, but I worked on them and looking back, at the time, it was how we did things.

Without trying to be too pretentious, lighting, like any art form, is going to develop and change over time, just like any branch of the arts. You wouldn’t say Turner is better than Rembrandt, they are each of their time and both valid.

Of course, not many present day LDs would be happy today producing pictures similar to those of 50 years ago, so if these new episodes were meant to recreate the feel of the originals, perhaps the production should have employed some of us old timers that are still around and who worked through, and knew, that era !

Dave Buckley

My wife and I watched all three episodes and enjoyed them.

As I had worked for TV Training, I was pleased to see comedy done before a studio audience with multiple cameras – as such shows were done originally, and which was the way TV Training trained production staff.

I take it that the scripts the production company were working from were full camera scripts?

It was obvious that the opening titles had been remade and more to the point, the edit of the song during the titles to make it fit, had been redone and didn’t jar at all.

According to an item in a paper, the show was shot at Pinewood, and the audience had to be asked to ‘calm down’ as they got a bit enthusiastic at times with catch-lines, although I only noticed this when Jonesy came out with “…they don’t like it up em!…”

Bernie Newnham

I must admit that I’ve always had somewhat of a bee in my bonnet about Television Centre lighting, almost from when I joined in 1966.In the early nineteen-sixties I really really wanted to be a BBC TV cameraman. I spent hours reading books from the library – Dewey Decimal 621 maybe? Anyway, the book I read several times was “The Technique of Television Production” by Gerald Millerson. Eventually, in late 1966, I was there, dragging cables (for years). One day I worked on “Christ Recrucified”, in TC1 with crew 2. The lighting man was going to be the legendary Gerry Millerson, and I looked forward to seeing the great man at work. The set was a Cypriot village, burning in the noonday sun. In the opening shot a man came in from the hills, nearly dead from exposure. He staggered across the town square in a huge wideshot – followed by three large sharp shadows. I was horrified – this man, who I had given years of respect to, didn’t know that we only have one sun.And from then on, I wondered why Television Centre lighting people didn’t know that daylight comes in the window: all that stuff we learned at Evesham about keylights and backlights had its place, but if you wanted anything realistic – and I for one did – you had to just stand in your living room and look – really look – at how the light works. After I left cameras in 1977 I didn’t visit the studios that often, but at some point things changed rather rapidly – suddenly all the sitcoms had lots of pieces of cyc cloth hung around the front of the sets. Soft light at last! These days everything has huge reflectors everywhere, though that’s a whole lot easier if you’re only using one camera.So – though I have great respect for Howard and Duncan, even more for Bob Wright, and none at all for G. Millerson – I still wonder why it took people so long to notice that daylight comes in the window.Back at “Dad’s Army”, I found the supersharp front and end a little off-putting. A small amount of effects work would have given a better context.

Dave Newbitt

Probably shouldn’t say this, but in my time Gerry Millerson was a byword for all talk and no performance.

Barry Austin

I suppose that’s been the big change in lighting over the years, the change from “classic” lighting to “natural” lighting.

I remember Henry Barber (what a smashing man!) lighting some long forgotten sitcom, it had the usual 3 sided sets with the open side towards the audience: this particular set was a travel agent shop, the missing fourth wall being the shop window to the street. Henry put up a long strip of cyc cloth above the cameras and bounced a load of light off it to simulate daylight through the fourth wall window, to my knowledge the first time it was tried on a sitcom. To those of us indoctrinated in classic TV lighting, this looked wrong, light coming from downstage instead of three quarter back lights as we’d been taught, whatever next, but I have to admit, it looked right in a realistic sense.

I suppose we were following the film industry, in films in the 1940s each close up of the leading lady would have a classic, slightly upstage of her eyeline, key light no matter what situation she was in, just watch “Casablanca” and look at the lighting on Ingrid Bergman: it wasn’t “real”, but, boy, did she look good. I suppose that all changed with Cinema Verite and the new wave. Now realism is everything, people have got so good at it it’s hard to tell if a shot is lit at all.

Whether the close up of the leading lady is better or worse than in days of yore is in the eye of the beholder.

Quite agree with you on the relative merits of Bob Wright and Gerry Millerson, in their day Bob was simply the best both as a lighting man and as a person, Gerry wasn’t.

Alex Thomas (aka “Woolly Moth”)

I remember Gerry Millerson’s habit of placing a lamp on a 5 foot stand right in the middle of the “fourth wall”.

It made it very difficult to get a central wide shot. I couldn’t understand why he couldn’t add filler from a soft lamp slung from above.

His “horse” name was “Rhino” and Frank Rose (aka “Horse”) who named us all got it exactly right.

I remember Gerry asking us all to request his book in our local library so that it would boost sales.

I am sure that none of us did.

Peter Fox

A BBC Ealing film drama that stood out for natural lighting was “Days of Hope” starring Paul Copley and lit by Tony Pierce Roberts – and that was in 1975. It really was quite a break through in BBC TV lighting and it soon fed through to (some) appropriate TVC lighting. Howard King was a pioneer of those big cloth based soft lights suspended over the set, Bob Wright’s trick was to bounce (tons of) light off the cyc (a pain for cameramen as the light washed out our viewfinders!) but lovely to look at (on the TV!).

Bernie Newnham

Another thing that annoyed me was that engineers always felt the need to put in lots of video peaking. Every shot looked like it was live. This didn’t matter on factual stuff, but for period drama that looked like it was looking out the window, it really wasn’t a good style. The worst material was when they first started shooting drama on electronic OBs. “The Pallisers” (I think it was), looked like “Eastenders” with fancy frocks.When I was senior enough in Presentation, and had spent a few hours chatting up our local engineers, I had learned about Contours, the peaking knob on a Link 110. Every so often we needed to do live pictures in Pres A – I remember strawberries and cream for Wimbledon. I’d say “Turn down the contours”, and after a certain amount of fuss (“You can mark it and put it back!”), I had a much more natural look. No peaking in the modern world.

Ian Hillson

Well said Barry! Those were the days when we engineers came to work, turned on the kit, and were pleased if it worked.

Pictures looked rather electronic (until LDs started using filters) because tubes were small and BBC designed PAL decoders were soft! Pictures looked a lot sharper on home tellies.

Sara Newman

I worked on “Sons and Lovers” in the 1980s with Geoff Feld and Garth Tucker. The Lighting Director had visited the locations where the scenes were set and made every effort to replicate the lighting as close to real life. There was a lot of mutterings as he seemed to take ages getting the light from a window correct. It was fascinating as there was lots of discussion at the time about the shadows and how they would appear on the suburban TV set.

There was also hours of discussion regarding the candles used in the production and when I was training the endless discussion on cameras able to work in lighting less than 1 lumen.

I had worked in the film industry before coming to the BBC and was amazed at how little time was spent on lighting scenes. One scene with Vanessa Redgrave in one of the films I worked on took over an hour not to mention the tweeking between takes for a single camera shot. Obviously economy of scale: time gives greater flexibility. I did my Lighting 1 and 2 at Evesham and found that it is a difficult skill in practice for multicamera.

Doing my degree course, Millerson’s books were on the required list. I realised after working in the film industry they had limited relevance but were useful for reference. Later working for the Foreign Office in Africa I used some excellent BBC training books which I gifted to the Television services. I still have my copy of “The Grammar of Television Production” (Davis/Wooller) though.

Cameras have changed progressively over the years and their tolerances are amazing: also lights have changed. I see stuff now that makes me cringe with camera shadows and stuff that would never have been allowed.

I saw all of the “Dad’s Army” and I thought they were very good. Much better casting than the film from a few years ago.

Ian Hillson

I felt the 2016 film would have benefited from having John Sessions play Mainwaring, as he did so brilliantly in “We’re Doomed!” (The Dad’s Army Story).

Pat Heigham

When I transferred from TV to the Film Industry, and was Boom Op on a good number of features, I found the BBC training invaluable in sussing out the DoP’s lighting plot, to see which lamps would give problems to the boom.

One commercial I worked on, shot at Hatchlands, a National Trust property near my home (probably the nearest location I’ve ever had!), was the first Nescafe Gold Blend of the subsequent series. The DoP was none other than the great Freddie Young. He paused by the sound table and enquired who was the boom operator. Me! Asked me my name and said: ”I’m Freddie, and you won’t have any problems”. Standing in the artistes’ position, I took a look – perfectly textbook standard 3-point lighting – key, fill, back.

I learned some new words in this industry: ‘Charlie Bar’ a thin strip flag to put a shadow across the lady’s bosom to enhance the cleavage!

The name of a certain lighting effect has derived from its first use in film. One example is the “obie,” a small spotlight that was designed by the cinematographer Lucien Ballard (1908–1988) during the filming of “The Lodger” (1944) in order to conceal the facial scars of actress Merle Oberon. I saw this in use, later, mounted above the lens and it was fitted with a shutter, so that when the camera tracked in, the brightness could be progressively reduced.

Some ‘new’ DoPs favoured soft light all round, and built walls of poly to bounce light off – this made it physically difficult to get the boom in, but lessened the shadow problems.

Alan Taylor

I did a several hour long interview with Freddie Young, and of course was rather thrilled at the prospect of meeting him. It became clear while we were travelling to site that our Director of Photography (DoP) didn’t know who Freddie was, so I explained to him that Freddie was a living legend, having been David Lean’s cinematographer for his epic movies and countless other famous movies too.

As we were setting up, Freddie walked in and chatted to the crew for a while and our DoP tried to ingratiate himself by saying how much he admired Freddie’s lighting on “Brief Encounter”. Freddie smiled and explained that it wasn’t one of his movies.

When I switched from TV drama to film drama, one of the first shoots I did was with a lovely cameraman who warned me that he was using some rather wide angle lenses and that I should consider using radio mics. I had already twigged that the aspect ration was very wide and although the shots were indeed wide, the letterbox aspect ratio meant that they weren’t very high and the actors would mostly be quite close to the camera anyway. Alternatively, if the headroom wouldn’t allow satisfactory boom coverage, the actors were going to be so small in the frame that we could easily post-sync the dialogue using a wild track recording made on location. I felt confident that there wouldn’t be too much of a problem getting a boom mic over the actors, and therefore situated my radio mics in the ideal position – still inside their boxes on my sound trolley.

Talking of wide angle lenses, when I set up “The Big Breakfast”, the tech facilities were provided by an Ex-Beeb type 5 Scanner, which I was very familiar with. The sound desk rapidly filled up and as we neared the date for the first live Transmission (Tx), I realised that we didn’t have spare channels available on the sound desk for standby microphones in case the main radio mics failed. Part of the style of the show was that the cameras were hand-held, using wide angle lenses, so I tried listening to the built-in camera mics, which because of the wide angle lenses were only two or three feet from Chris Evans or Gaby Roslin. The results were more than satisfactory and we didn’t need to bother with spare mics.

Geoff Fletcher

Two really interesting posts, Alan and Pat.

Having started as a studio cameraman and later Unit Managing on both OB dramas and film dramas, I found both the differences and the similarities fascinating.

We tended to use hidden mics and two very tall fish pole operators at Anglia, and avoid radio mics if at all possible. Anglia did a lot of drama productions and pioneered OB dramas with Weavers Green way back before I joined them. I was lent out to be UM on my only feature film type shoot too – “Diamond Swords”. I worked on the flying sequences shot at Fowlmere and Duxford. Thoroughly enjoyed it being a lifelong aviation buff!

Bernie Newnham

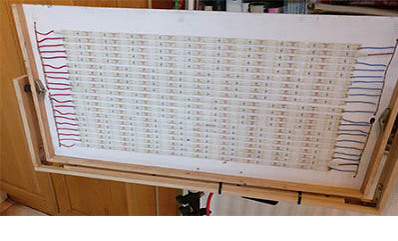

When I joined the BBC, if you wanted a soft light you used a ten-light – till Bob Wright came along and pointed a quarter of a megawatt at a full height white cyc in TC1. That really was a soft light.Now that I’m lord of all I survey at the Woking Area U3A video production group, I’ve been pointing redheads at reflectors, but I saw a design on YouTube for one using LEDS. And so I present to you 600 LEDs dissipating 12A at 12V, 144 Watts.

|  |

The power supply gets too hot to touch, though each LED only gets warm. I’m not sure whether it will be bright enough though, as I haven’t done a proper test yet. The black box at the rear bottom is my very last Maplin’s box.

Tony Nuttall

LED Ceiling panel £18.00 from LYCO Lighting for “Skype”, mounted on the wall behind my iMac. Not a bad soft light for Skype.

Good scatter from the back of the silver painted iMac! Corpuscular radiation and all that!

It does not clutter up the desk top of my desk with other lights. I use the Anglepoise for reading at my desk when the computer is not in use.

Pat Heigham

I worked on a film at Shepperton (“The Sender”), and as the main set was an American hospital and lit practically by fluorescents, the lighting cameraman used a bank of florescent tubes as fill. The only problem was that they caused horrendous interference with the radio mics. Luckily I had some Microns which were shielded with a metal casing, so worked well.

Nick Ware

Interference on radio mics from fluorescents was a problem that pretty much went away with the move from VHF to UHF and diversity receivers. I don’t remember ever seeing a professional radio mic Tx or Rx (transmit or receive) that didn’t have a metal housing. In any event, it probably wouldn’t have made a lot of difference as the metal casing isn’t usually grounded. More likely, the interference was aerial borne, or down the unbalanced mic lead (acting as an aerial). Receivers in those far off days were less frequency selective, i.e. more receptive to RF harmonics and spurious adjacent channel shash, and unless in a fixed installation, unlikely to be grounded either. We progressed and moved on, and now 80 or more radio mics plus IEMs all working perfectly on a Talent show is not unusual, despite a massive amount of flashing lights of various sorts.

Pat Heigham

Yes, things have moved on!

At the time, 1982, Tony Dawe’s Audios were heavily affected, but my Microns were clean.

As far as I remember, both makes used a Tx trailing wire aerial, but the mic input lead could have been unbalanced. The Microns had a case that encompassed the bottom of the Tx – Audios had a plastic base to contain the battery, so I reckoned that they were not fully screened?

I saw “42nd Street” at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, around 10 times (it was that good!) and discovered that there were 84 radio mics in use – some mikes were at calf position down the tap dancers legs, under the tights. I guess the desk was somewhat large! One wonders at the proximity of another theatre – “Mamma Mia” was next door.

I frequently suffer a dream nightmare, where I’m on a job, then discover I have no spare batteries for the Radios! Panic! It’s a relief to wake up!

Chris Woolf

There’s a great belief in “screening”, and it isn’t always justified. Certainly Faraday cages are excellent devices, and you wouldn’t want to be without them, but looking at the external structure of a radio mic and trying to gauge the level of screening from that isn’t helpful.

For a start, the real screening of all these devices is normally accomplished by very tight-fitting internal screens – the need to avoid even the tiny cracks necessary to make a battery housing open and close means that relying on the outer shell to do the work is little use.

Radio mics cannot be grounded in any conventional sense so an antenna cannot have a “ground” to “oppose” it. Generally the case and the screen of the mic lead act as a nominal “ground” and form a sort-of dipole with the actual antenna. These had to be trailing wires for the longer VHF wavelengths, but can be the nice little short stub for UHF.

Personal electrets mic are almost universally unbalanced. Unless they were large enough to use quite complex electronic circuitry they have to rely on a simple single FET impedance converter. That means that the connection to the TX is also unbalanced, and any signal induced in the screen of the lead cannot be excluded from the audio circuit – noise currents are inevitably connected into the audio. The filtering of both RF and extreme LF noise is critical, but can’t rely on simple screening.

That radios are as immune as they are noise sources is amazing, but to understand how they do it requires a very deep knowledge of their intimate circuitry!

Mike Giles

When I arrived in Bristol in 1965 they were already using a locally made aluminium housing which served as the reflector for probably half a dozen fluorescent tubes as soft light in the news studio, because the air conditioning wasn’t up to a full rig of conventional lamps. The sparks carried a starter in his pocket and fired up as many tubes as the circumstances required.

I have to confess I never saw anything wrong with the pictures, monochrome of course, and radio mics were never a requirement.

Alan Taylor

I did a series of “Murder Most Horrid” and one major location was on the umpteenth floor of a Canary Wharf skyscraper with huge glass windows. The Directory of Photography (DoP) and art department didn’t want Neutral Density on the inside windows and there was no way of putting it on the outside. Therefore, in order to match the light levels, the interior was lit with ten or fifteen 12k flicker free lamps.

I expected that they would produce an audible whistle, so I took along a portable parametric equaliser to notch out the whistle, but when I tried it, the results were disappointing. Either the whistle remained, or too much High Frequency (HF) was sucked out of the audio to be acceptable. I was crestfallen, but decided to record a wild track of the whistle and run it through a Fast Fourier transformation on my Mac to analyse the audio spectrum.

The spectrum revealed that the whistle was actually three separate whistles 100Hz apart, at around 8 kHz. My hunch was that they were the fundamental and two sidelines generated from multiplying the mains frequency, which would explain the 100Hz spacing. I assumed that by using a multiple of the mains frequency as a clock, all the lamps would run at exactly the same frequency.

I now knew what I had to deal with, and as a check, I was able to emulate a very sharp triple band parametric notch filter on my Mac and proved that I could eliminate the fundamental and both side tones without unduly spoiling the dialogue.

We shot the scenes without filtering and I later met with the dubbing mixer to show him what I had discovered. He was delighted because he too had experienced difficulties in notching out such whistles, but by using three very deep notches, the whistle could be removed very nicely. The exact frequency varied from shot to shot, presumably as the generator drifted, but the side tones were always exactly 100Hz either side of that main whistle.

Bernie Newnham

I seem to remember that when I went filming on 16mm the fluorescents always came out green for some reason.

Dave Plowman

You really need special tubes for filming, etc. These are much more expensive and have lower light levels. The common white and warm white being very much a compromise.

Bernie Newnham

Indeed, that is OK for drama, but it is not so OK when you walk into someone’s office for a quick interview.

Dave Plowman

“The Bill” sets were all lit by practical fluorescents – so from the 1980s. Later on, they were all changed to units with individual dimmers, as some Lighting Directors removed some of the tubes to lower the level: this was not ideal, as they weren’t designed to be opened up perhaps several times a day, and got broken.

So we changed from ordinary 50Hz types to high frequency ballasts, which are more easy to dim. And we rarely used cabled mics on “The Bill” – the poles had a Micron radio link from the very start. And on the live programmes, everyone had a personal mic all picked up from anywhere on the set with central aerials. There was never a problem with the florries producing interference.

I have dimmable high frequency ballasts on the lighting under my kitchen cupboards. The actual control is a simple pot wired back to the ballast. Unlike tungsten, dimming them saves the proportional amount of power consumption – and these tend to get left on as a ‘someone is at home’ light when out. This dates to well before LED days – but I’m still not convinced any LED yet gives the quality of light I want.

Chris Woolf

There isn’t really any great difference between fluorescents and white LEDs. Both use short wavelength light – UV for a fluoro, usually blue for an LED – and make a phosphor fluoresce with longer wavelength colours that give a similar effect to a classic hot body spectrum. Sometimes a yellow filter coating is added to make the light “warmer”. Neither light source can manage a continuous spectrum, so some colours don’t get rendered correctly, which is why the light doesn’t please. However LEDs have improved enormously compared to fluorescents and usually manage a far better Colour Rendering Index. That is partly because you only need a very small amount of phosphor for the LED, as opposed to many square cms for a fluoro. The modern “warm white” or “very warm white” LED – and particularly the fake filament type – give very attractive light, that can be dimmed down to ~5% if required, and with a CRI of >80. Try one!

Dave Plowman

I think Chris Woolf must be referring to very basic florrie tubes. Better ones use a tri-phosphor coating.

I do have warm white LEDs in the living room with a suitable dimmer – purely as working light. All other lighting circuits there – used when relaxing – are still tungsten.

Chris Woolf

Whether halophosphate or triphosphor the spectra are still primarily discontinuous. The latter give a better theoretical CRI (at greater expense), though it still has a lot of holes. The greatest problem is where an object has a narrow reflectance spectrum which doesn’t fit well with the narrow transmission bands of the phosphors. So although a white looks good to our eyes, which have broadband colour receptors, these particular objects have an incorrect colour and luminance compared to continuous spectra illumination. LEDs can benefit from similarly well-chosen phosphors, but need only a few mg as opposed to a long tubes-worth.

Mike Giles

I was on a Bristol OB at Slimbridge when the lighting Engineering Manager (EM), Jolly Julius Jack Belasco, might have wished for low energy lamps.

For an interview with Peter Scott in his study/studio, he had placed one of the backlights right next to the enormous plate glass window which looked out onto the lake where Bewick’s swans overwintered.

As you may have guessed, the glass cracked, but only down one side, so the curtain was hastily drawn across the damage before the great man entered the room. There was much fear and trembling in the camp about admitting what had happened before the interview took place, because it was totally verboten to go anywhere near the outside of the window until the Bewick’s swans had gone back to Siberia – quite some time ahead.

Not sure who was given the task of relaying the bad news – probably the Stage Manager, Jeff Sluggett, as I recall.