Technical Operator – Dolly Operator One (Dolly Op 1)

I was in the fast Arts stream at Reading School. At the end of the fourth form, we went straight into a two-year “A” level course, taking “A” levels at the end of the first year sixth. I elected to do French, German and Latin at “A” level, thinking it would be easier to learn a language whilst at school. Unlike my best friend at school, who was in the fast Science stream, I ended up at the end of “A” levels with no idea of what I wanted to do, except that I certainly did NOT want to go to university to study French (literature) or German (literature) or Latin (literature). Keith meanwhile was all set – after a further year in the sixth form – off to Southampton to become a “scientist”.

What to do? What job to get? Only had Maths and English “O” levels (because in the fast Arts stream we only did two!! (oh, and Latin, as I, along with most of the class, failed Latin “A” Level but did get an “O” level pass in consolation)) – most places wanted at least 5 ”O” levels.

Meanwhile I had to think about a job. Although my main interest was in steam locomotives and railways, I had always been interested in film and television – the practical aspects and the final, consumable, output – the shows. I had set up the school film society, when one of the teachers found a clockwork 16mm Bolex camera: we filmed the start of the school’s Gilbert and Sullivan production one year, and made a simple stop frame animation using the chalkboards. I was a member of the school Photographic Society. I was also a keen member of the school Electronics Society (all after-school activities), where we made things like amplifiers: such care routing the feed cables past the valve sockets in the chassis to minimise hum. About this time I also took ‘Wireless World’ and looked at the series they ran on making your own simple, step-by-step operation, digital computer (in the early 1960s!!).

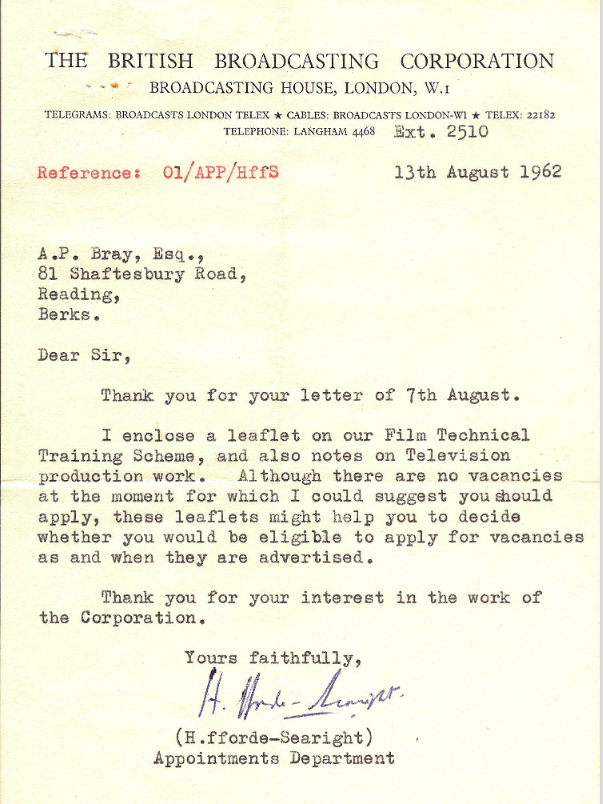

Because of my interest in film and Television in particular, I wrote off to the BBC to find out if there were any suitable vacancies – no, there weren’t!

I stayed at school for another term (Upper Sixth): at that time it was possible to resit – or sit for the first time – “O” level exams in December: and so I arranged to take English Language and Physics in the one term. This would then give me the 5 “O” levels.

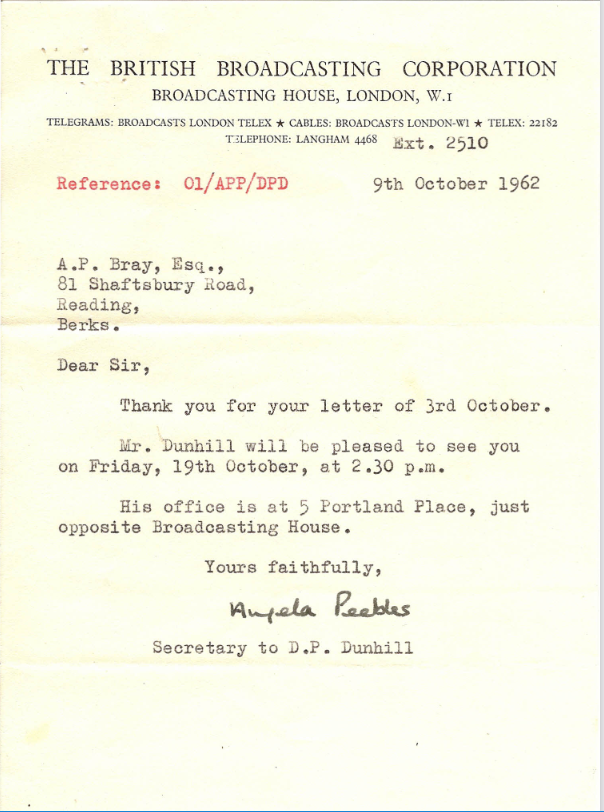

And then there was an advert, in a national newspaper, for a trainee film cameraman at the BBC! I applied and got an interview.

Friday 19th October was my birthday! I thought that this was a good omen. This interview was just two weeks after The Beatles had released their first single, “Love Me Do” and the first James Bond Film, “Dr. No”, had opened in London (Friday 5th October. It was the start of an era.

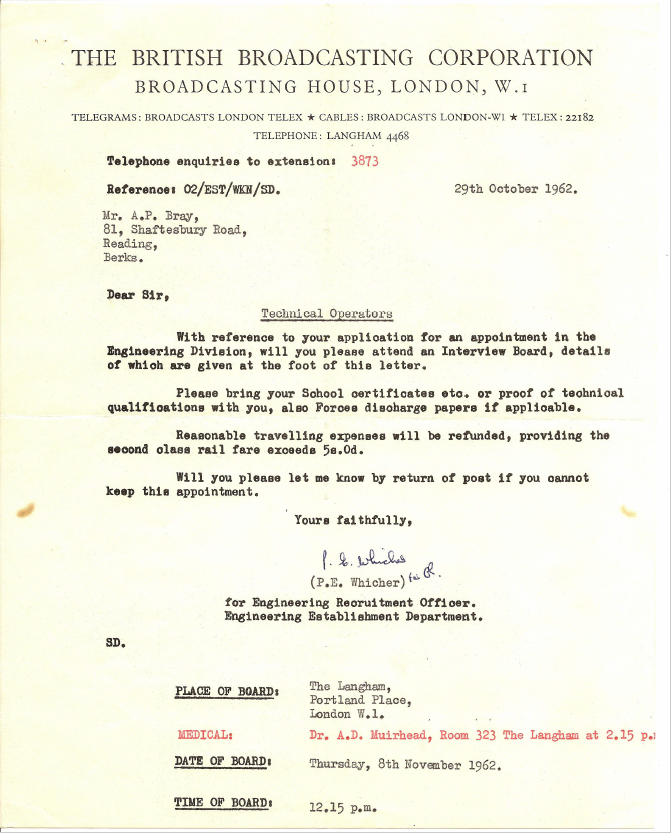

At the interview, Mr Dunhill asked several technical questions – such as “When someone walks through a doorway, when should you cut the shot from one view to the next?” But I was also asked other questions: “Who is the Foreign Secretary?” and other questions about politicians – that sort of thing. At the end of the questioning, Mr. Dunhill said that they were actually recruiting for NEWS film cameramen, and I was not up to speed with all the political figures needed to succeed in that role. But, he said, the BBC are recruiting for Television Technical Operators, and that he thought that I would be a suitable candidate. So he arranged for me to apply right away. This was really where I wanted to go.

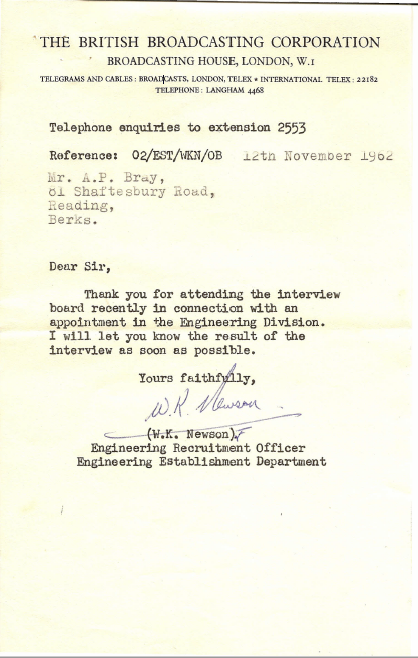

I don’t remember much about the board interview, except that it was in The Langham.

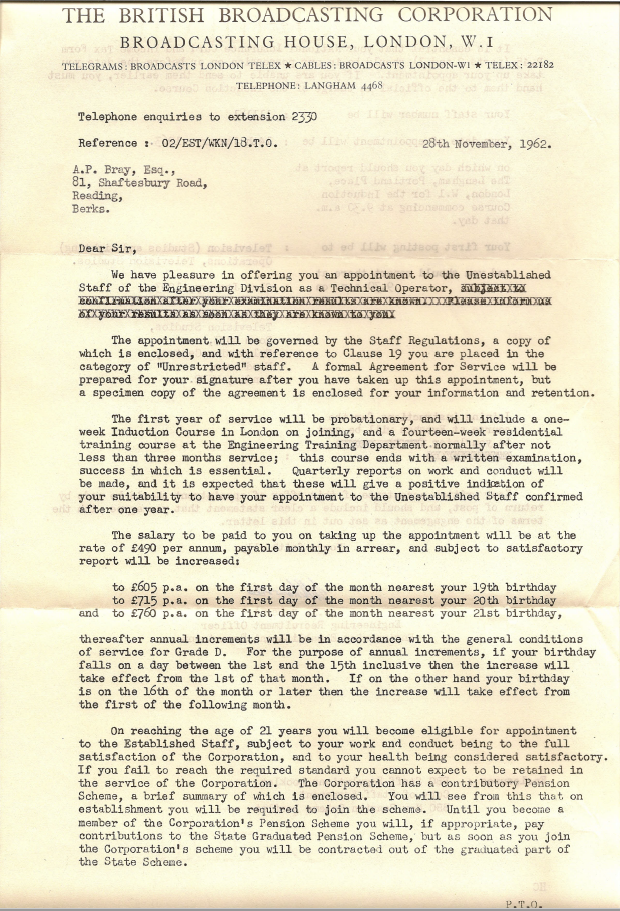

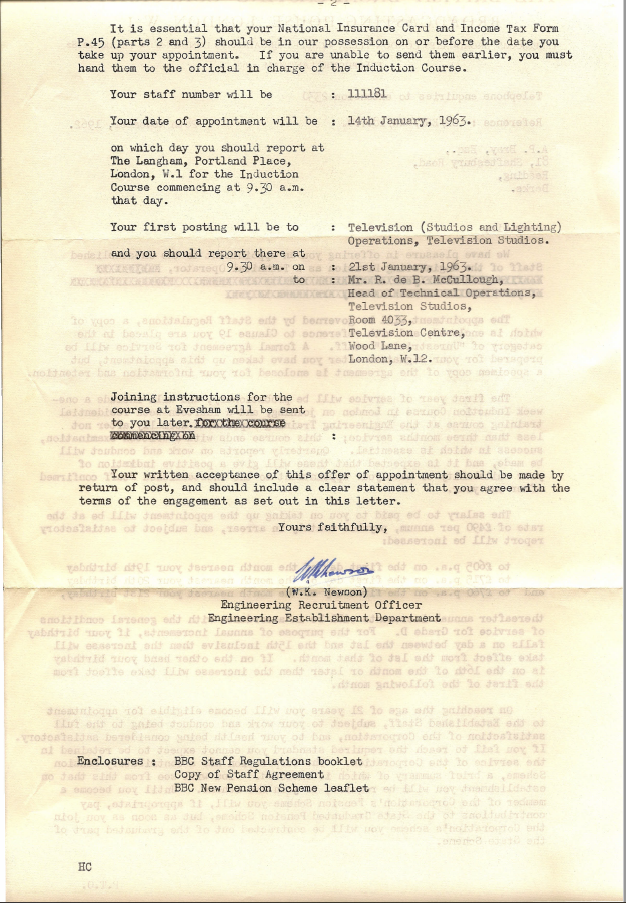

I got through the interview and was offered a position!

I was in!! Working in Television for the best broadcasting organisation in the world!! I accepted the job offer immediately.

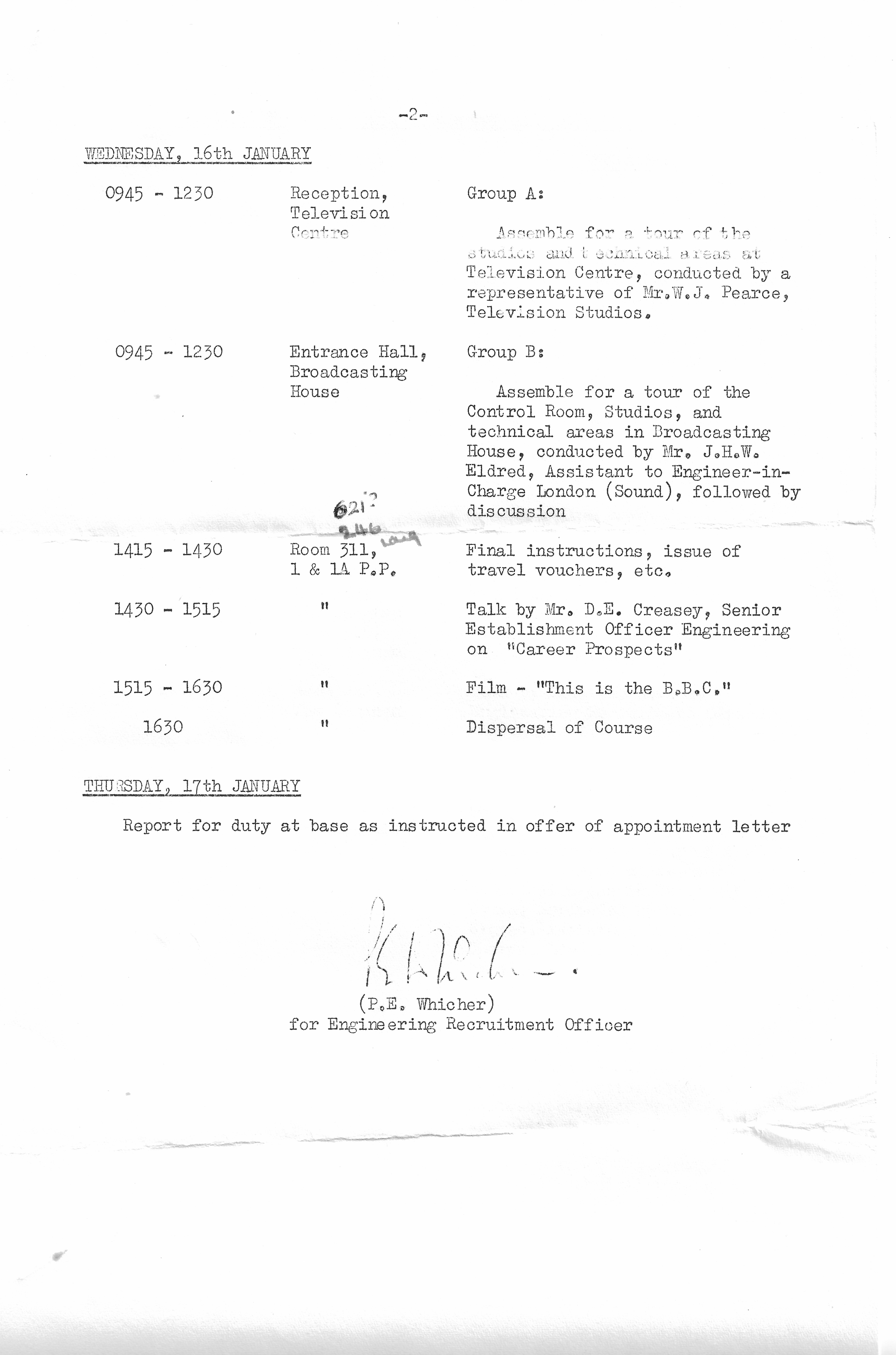

But the Induction Course had been reduced from one week to just three days.

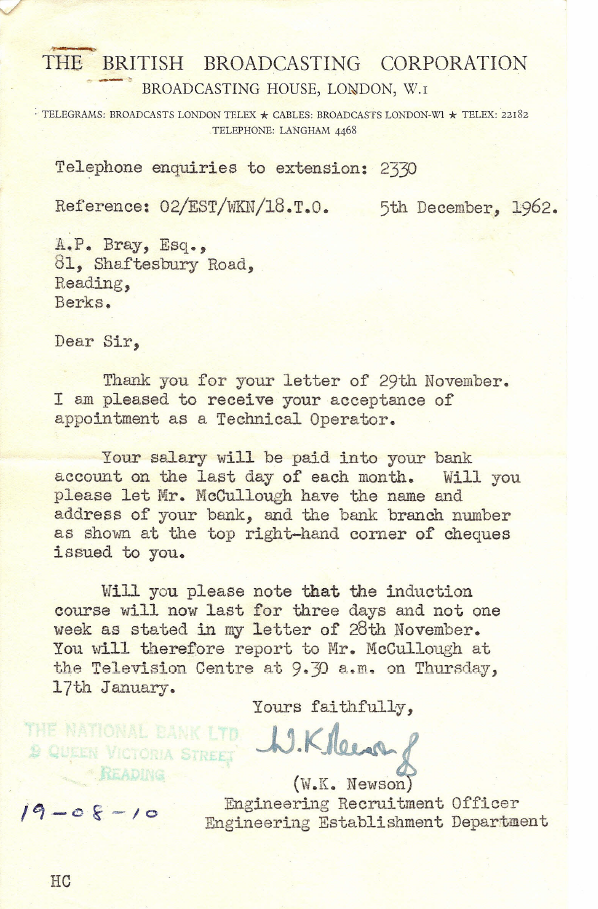

The Induction Course was only three days:

And so it happened that on Saturday 12th January 1963 I had been sitting at home at 5.25 in the afternoon watching the second episode of “The Chem Lab Mystery” and on Thursday 17th January 1963, following my appointment to see Mr. McCullough, I was sent to Studio E Lime Grove to become part of the studio crew, Crew 7, working on the next but one episode (episode 3) of “The Chem Lab Mystery.” The Senior Cameraman was Mike Bond, who was a very nice person and a great person to work for, and who took pity on this raw inexperienced youth on his first day – and let me go home “early”.

I was a BBC TV Technical Operator! It was a dream. Working for the BBC – everywhere (at the time) regarded as the very best broadcasting organisation in the World. Whatever else, I was working for a premier industry. The job was almost unique – there could only ever at maximum be 19 people doing exactly my job on the television TO studio crews.

After some four months it was off to the BBC’s Engineering Training Department (ETD) at Wood Norton Hall near Evesham –now a swish hotel.

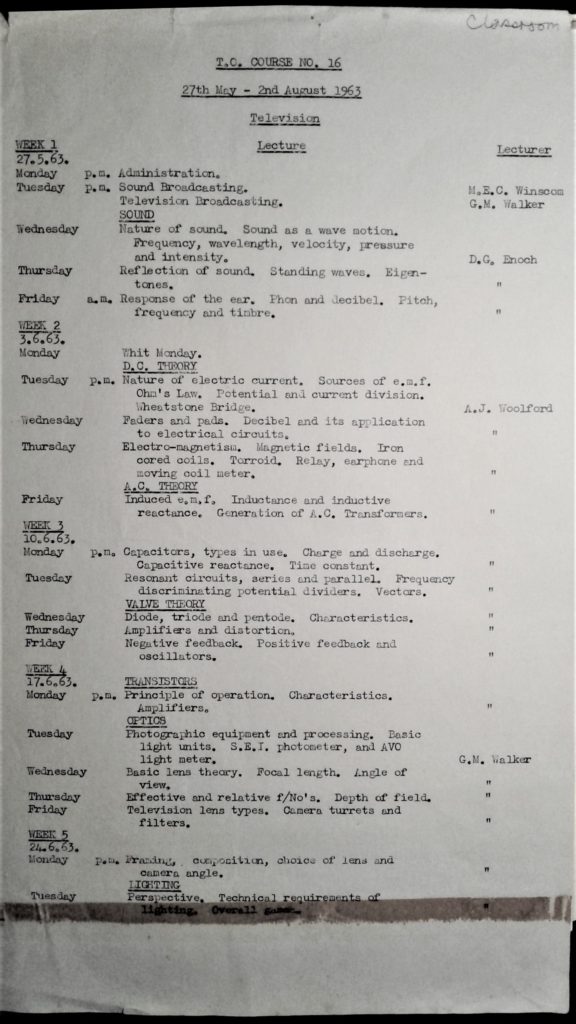

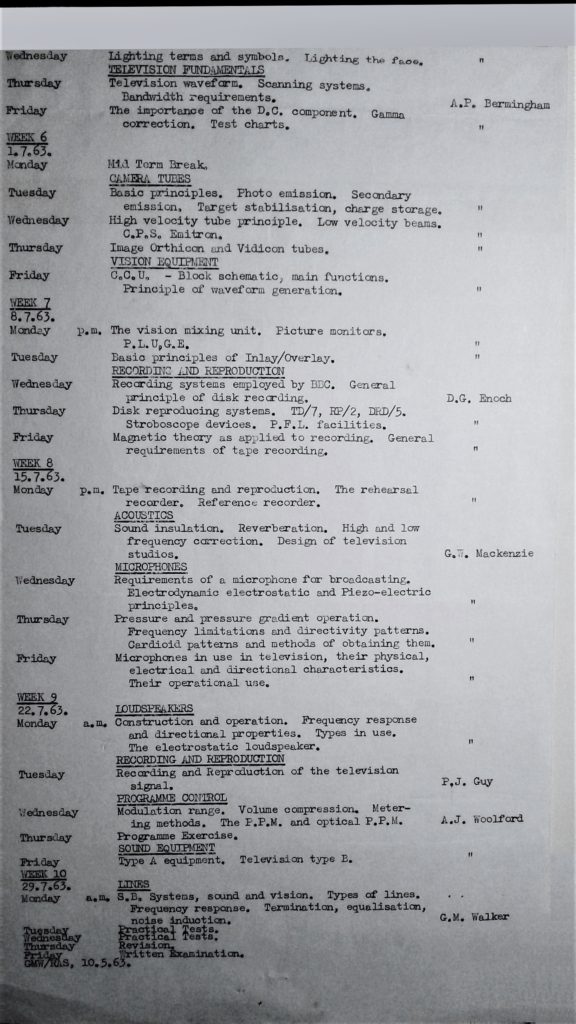

Course TO 16, 27th May to 2nd August 1963.

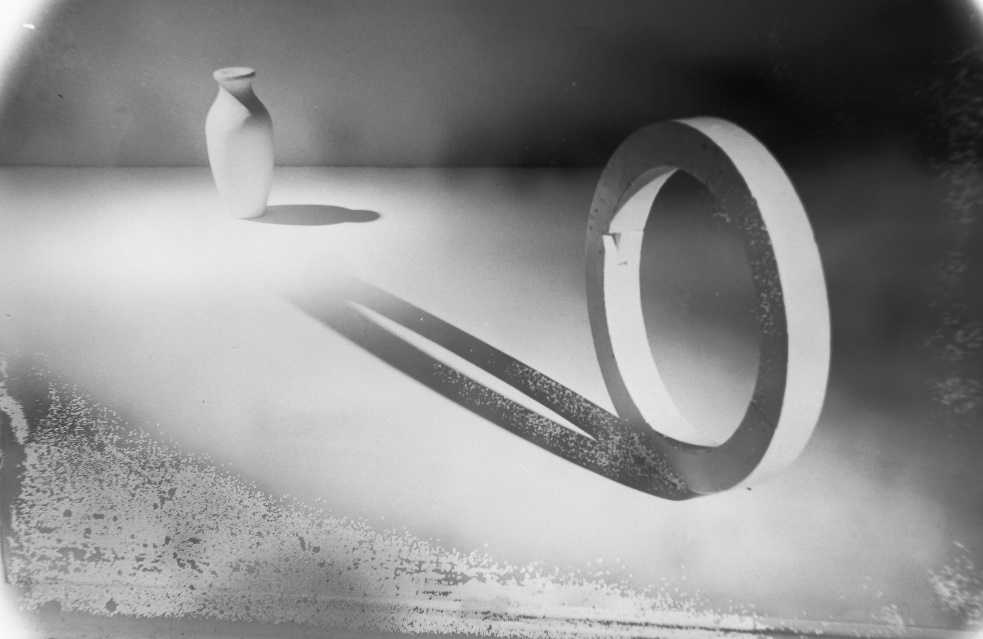

The BBC gave us a good general training in camerawork and how the cameras worked, microphone placement and sound systems, how to light a studio set, in general all the skills needed technically to get a production on air. Lectures were interspersed with practical work: one example was to light the two pieces of still life so that it was interesting and visually attractive.

One day we were mixing between two gram decks. The idea was that you set a 45 or 78 rpm record going on one deck, then, as it was playing, you had to cue up the same record on the second deck so that you could then mix between the two sound sources with no “join” (this was for practice to go from one news recording directly cut on acetate to the continuation on a second acetate). The record was Jimmy Shand and His Band “Eightsome Reel” (very popular at one time). It was a very tricky job – very little defined differences between the phrases but we had to hit the exact changeover. For light relief we decided to take a feed from The Light Programme – as it was then – to mix to – only to find that the Light Programme was playing exactly the same record!

The lectures were basically exercises in dictation: on the very first day, we were told that this was not like a university, where lecturers lectured and students took notes as and when – Oh no! each lecturer dictated the notes and these notes were all written down verbatim by the attendees.

I am very grateful to Mike Du Boulay who has provided the programmes of lectures for TO 16:

The end of the course was marked by a written examination and some practical tests. One of the practical tests was that the complete course had to mount its own television programme, using whatever resources could be found.

We found a 16mm Arriflex turret film camera, and used this to provide the starting telecine sequence for the programme – we had sussed out the telecine machine at Woodnorton. We managed to get our film processed in a timely manner – thanks to Mr. Birmingham! But this was a negative, so the telecine had to be switched to transmit the film as a positive. I got landed with operating the telecine.

Surviving fragments of the 16mm film used for the programme at the end of TO 16 course.

In the club … On the road hurrying to make the programme …

I was film cameraman for the car sequence, mounted in Chris Pocock’s ragtop sports car, and as we turned into the gate, I changed the speed of the camera to take fewer frames pers ec, making the film, as transmitted, look speeded up. This was not easy action to achieve on that film camera – an ancient detachable film cartridge, three lens turret Arriflex: the speed control was at the front left-hand side bottom. The “Script”? We were all in the Club at Evesham, got a phone call to return hurriedly as a change in schedule meant we were to go on the air live!

The final practical “exam” interesting and basically straightforward – a Marconi Mk 3 I.O. with no picture. The test was to get a correctly set-up picture back from the camera.

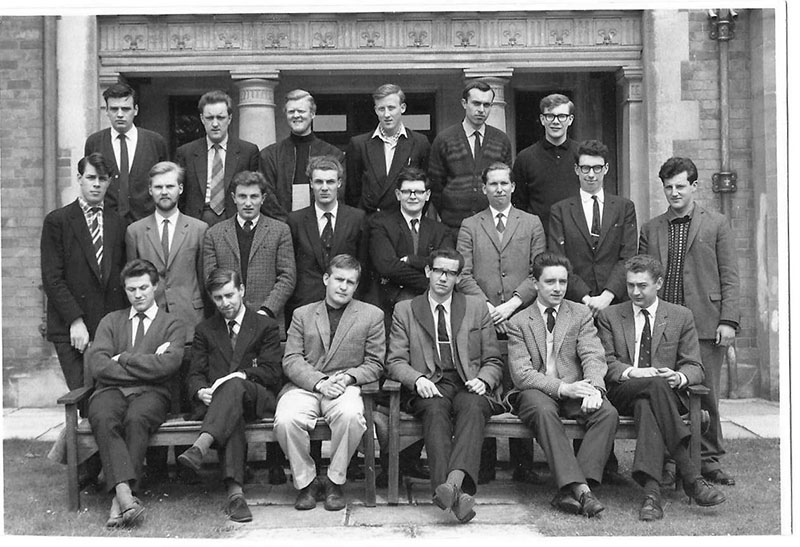

The attendees on Technical Operators Course 16 (T.O.16 ):

Then it was back to the studio crews – as a fully trained technical operator.

The job was defined as irregular hours – you just had to keep a diary. Four weeks’ notice of days that you were scheduled, and two weeks’ notice of the times that you were scheduled. It was great having different days off to the rest of the British work force, not having to go shopping on the one same day each week, being able to go out midweeks and so on. The downside was the irregularity: I joined on society that met on Wednesday evenings, and a couple of weeks in, the crew got “Softly Softly” – every Tuesday and Wednesday. I joined Reading Ramblers which met Sundays – and then the crew got “Not Only But Also” – on Sundays… The other downside was keeping track of Extra Duty Pay (or overtime). The first eight hours in any thirteen week period had to be taken as time off: above those eight hours you could submit a claim for EDP. Every week one member of the crew was despatched to the Admin office (or Jennery) on Shepherd’s Bush Green to collect the overtime records for the crew.

The dress code for Technical Operators was acknowledged to be “smart casual” – which in the 1960s meant shirt and tie – and usually a white shirt. All footwear had to be “soft-soled” – for which we got an allowance. So for my first years in work, my shoes were “Desert Boots” – soft-soled and comfortable. The Beeb at this time also prided itself that it was run “like the Civil Service” – that may have been said during the Induction Course – and it had pay grades like the Civil Service – and a plethora of initials for managers and executives. Our boss was H.T.O.Tel.S (head of Technical Operations, Television Service).

The first official position that any new recruits had on a crew was Crew Relief (mainly sound) or Crew Relief (mainly vision). I was lucky enough to be Crew Relief (mainly vision). I was never very much interested in sound, but the BBC training made sure that you had a go at doing everything, and so I did my stint learning about sound as a boom operator, sound rigger and goodness knows what else for sound.

Learning how to operate a microphone boom was very interesting (and technically difficult) and one of the things it taught me was about sound perspective. This was in the days of 4:3 aspect ratio Black and White television. Sound perspective meant that the boom operator should position the boom microphone over the point of view of an appropriate person in the current shot, and pointing in an appropriate direction, so that where possible the the sound perspective matched the vision perspective: someone speaking further from the camera should sound more distant.

For example, on an over-the shoulder two-shot, the microphone was placed over the head of the person with their back to the camera and typically listening to the conversation. As the shots changed to the “companion” over-the-shoulder two shot, the boom operator had to move the position of the microphone boom to compensate, so that it was now over the head of the other person – who was now the person with their back to the camera. This was it was quite hard work because normally on this sort of set-up the boom operator not only had to swing the boom arm around but rotate the microphone in its cradle about 90 degrees or more – and usually have to rack in or out to compensate for the positions of the two actors. The microphone most used at this time in the boom was a heavy mic – the STC 4033 – which in fact was a double mic as it included a ribbon mic and a moving coil mic.

There was a lot more to more to sound perspective than just this though, because the boom operator also had to compensate for or check the sound perspective on wide shots – keeping the microphone head as close to the actor(s) as possible to pick up the best sound while also keeping out of shot. keeping the microphone out of shot was relatively easy with turret cameras because the boom operator could see which lens the camera was using at the time and work out the field of view, but with cameras with zoom lenses this was a much more difficult operation. I have great respect for the sound guys who consistently managed to balance up the needs of getting good sound with the ability to keep the microphone – and microphone and boom shadows(!) out of shot. This of course required cooperation with the camera guys as well, because the cameramen had to frame up a good-looking shot without a huge amount of headroom (unless specifically required).

Other training on the sound side of things included setting microphones in their correct position for the sound and/or performance – and also rigging the PA, particularly the microphones on the PA system for audience shows. The worst thing about derigging PA was having to coil all the cables from the audience reaction microphones.

Another good piece of learning about sound was how to manage the sound from an orchestra. We did not mike up every instrument in those days: in the 1960s the way of recording an orchestra was to sling a pair of microphones about six feet behind and six feet above the conductor’s head, on the assumption that it was the conductor who was going to balance the orchestra. The two microphones used at this time were an AKG C12 capacitor mic (possibly) and a 4038-ribbon mic in combination.

After my stint on sound it was back – thankfully – to Cameras! The dogsbody on the crew – the Crew Relief – more likely than not had to “cable-bash”. The camera cables were thick and were clamped to the bottom of the camera pedestal: from there they were laid across the studio floor to an appropriate camera connecting socket mounted on the studio wall. The socket to use was marked clearly on the studio floor plan.

The slack in the cable was “figure-of-eight”-ed so that the cable could e pulled out with ease and without tangling. As the camera moved about the set, the cable-basher had to make sure that there was always enough slack – the last thing a cameraman wanted if he was doing a difficult track on a pedestal was the weight of the cable dragging behind the pad. The cable basher would try and make sure there was enough cable for the pedestal to move.

When the ped cameras – and particularly and crane mounted cameras – moved away from the scene, the cables for each camera had to be figure-of-eighted neatly in a suitable position, not fouling the firelanes, not impeding access to the set for specific shots, not in the way of the artists, make-up girls, dressers and other people in the studio. The camera cables were usually quite amenable to being “coiled” as a figure of eight, the loops crossing one over the other, and then could not get tangled. This was true even when mains cables (or monitors and/or “headlights”), video cables (for monitors) and/or Autocue (or Teleprompter) cables were looped around the main camera cable and secured with camera tape. The worst thing about cable-bashing was the sharp debris and dust that really bit into your hands.

Especially on live drama series and live music programmes, any available person on the camera side of the crew was involved in “cable-bashing” – making sure the camera cables were not impeding the camera or any other cameras. The sound guys had their own problems, sorting out the cables for the boom mics, especially if the sound boom had to trundle round the studio.

The next step up from Crew Relief (Mainly Cameras) – and the cable-bashing – was Dolly Operator 3 – still on grade D. The Dolly Operators tracked (drove) either the Vinten Motorised or the Vinten Heron crane – or was part of the crew swinging and tracking the Mole crane (the Mole Richardson or Motion Picture Research Council crane). At this time in the 1960s the Mole had more stories told about it than any other piece of equipment in the BBC and BBC television studios. One story that went the rounds was about a live “6 5 Special” (Saturday late afternoons) where the Mole arm counterweight bucket hit one of the performers on the back of the head, effectively knocking out – and nobody could tell the difference on the actual production as it was transmitted live.

I never really liked swinging the Mole Crane because it was always very difficult to get the precise point each time – so the Mole team (tracker, swinger, cameraman) would set up a shot that was acceptable to the director, to the cameraman and to the actors – and then on transmission you would try to replicate that position. There is no real way of marking up the camera shot cards to indicate exactly how the Mole crane arm was positioned for that shot – height, inclination, angle to the main platform – and in any case all this depended on the tracker putting the chassis of the crane in the right place every time. Working the Mole Crane was completely a team operation and I think that’s one of the things that the BBC really taught me: how to operate properly as a team. You had to work as a team on the Mole Crane to achieve the shots and without too much finger wagging from the guy up front (no reverse talkback or talkback to the trackers from the cameraman in those days – it was all hand signals.

Stories about the Mole Crane are in various places on the Tech Ops website (one, for example, is my page about The Good the Bad and the Ugly). Driving (tracking) the Mole crane was quite fun – I just didn’t like swinging it very much. Some people were more effective at swinging the crane arm than others and some people, especially the stronger guys, could just swing the crane bucket around like nobody’s business.

The Vinten Heron Crane was a very different beast. It was completely hydraulically operated and there were two variants, one which was meant to be driven using the directional control hand levers and the later version which had been redesigned so the foot pedal could actually be used as an accelerator – this allowed you to take-off on a track or crab much more smoothly. The Vinten Heron had an electric pump for the hydraulics, and the theory was that you could charge up the hydraulic accumulator using this electric motor pump (which obviously made a sort of pumping noise although quite quiet in absolute terms), and then the tracking, crabbing and craning could be done without the motor being used, relying entirely on the hydraulic reservoir. Most of the time, however, the pump was operating because of the need to do quite complicated moves – craning and tracking or crabbing at the same time – this could soon exhaust the accumulator. By the way, on the Vinten Heron, to change from “steer” to “crab” you had to line up a marker or tell-tale mounted above the left-hand rear wheel so that was the rear wheels were pointing directly forward, and then you could engage a clutch to make all wheels steering. Sometimes this needed careful planning during rehearsal.

When you got to be a Dolly Operator (and the progression was Dolly Op 3, then Dolly Op 2, then Dolly Op1), if the senior cameraman was feeling generous towards you, he would put you on a camera for some of the less prestigious productions, and this was very useful learning curve. Some of the more challenging shots happened on productions like schools’ programmes where some shots needed tricky tracking in and out on a small caption to change the size of the picture – pulling focus while tracking a heavyweight pedestal and camera just a few inches close to a caption was quite a challenge. Not many zoom lenses around in those days!

I was very lucky that for most of my time on the studio crews I was crewed up as a cameraman.

I was always on general purpose crews (like crew 7), and we did a complete range of programs -“Gala Performance” in LG studio E with Julian Bream playing Rodrigo’s Guitar Concerto one day, then “Play School”: every day was different. Some programmes of course dragged like h*ll: Party Political Broadcasts were horrible to work on.

Some were more exciting: one day we were called in at 15:00 in the afternoon to do a (at that time) astounding live Telstar transmission to the US, which we did at 01:00 the next morning …

It was an exciting time to be in BBC Television. Television Centre had opened studio TC3 on 29 June 1960, with TC2, 4 and 5 opening over the following 14 months – so those four studios had only been operational as a group for about a year and a half. TC1 opened on 15 April 1964. BBC-2 was launched on 20 April 1964 although the first full programme to go out on BBC-2 was “Play School” the next day. That first week of “Play School” had been pre-recorded on VT before the start of BBC-2, but I worked on the second week of “Play School”, the first to be recorded after BBC-2 had started.

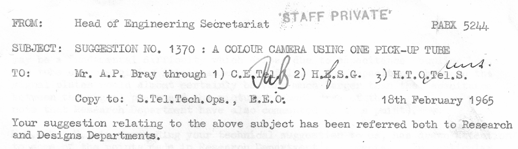

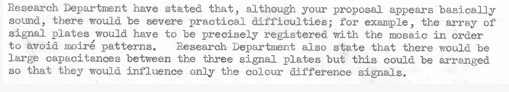

Around the end of 1964 I submitted a proposal for a single-tube Colour Camera – the BBC encouraged everyone to submit technical suggestions. The design was based on technology already at that time just about out-of-service. The suggestion went through both BBC Research and BBC Design departments, and the rejection letter the following February did not dismiss the concept completely out-of-hand (just snippets from the letter shown here):

…

…

And back to camera work ….

I worked on three series of “Dixon of Dock Green” – in one episode, Andy Crawford (Peter Byrne) had been wounded, and he spent the whole episode either in bed in hospital or in the bed at home: all he had to do was move from one to the other. I worked on three seasons (two, actually: the second series was split with a break over Christmas) of live “Softly Softly”: I had great admiration for all the actors, who were performing this week’s episode, rehearsing the following week’s episode, reading through the following week’s episode and so on. It was interesting to see Alan Stratford John’s performance tighten up during the two run-throughs on the Wednesday before transmission. There were plenty of other programmes in the mix – “Juke Box Jury”, for example – and especially “Top of the Pops”. There were a number of firsts for me on “Top of the Pops” – the first appearance of

- The Beatles (as a group) (“Can’t Buy Me Love”) – Film recording pre-record – TV Theatre – 19 March 1964, TX 25 March

- Sonny and Cher (“You Got Me Babe”) – Live TOTP – TC2 – 1965

- Jimi Hendrix (“Purple Haze”) – VT Insert – Lime Grove G – 30 March 1967

- Procul Harum (“Whiter Shade of Pale”) – Live TOTP Lime Grove G – May 1967

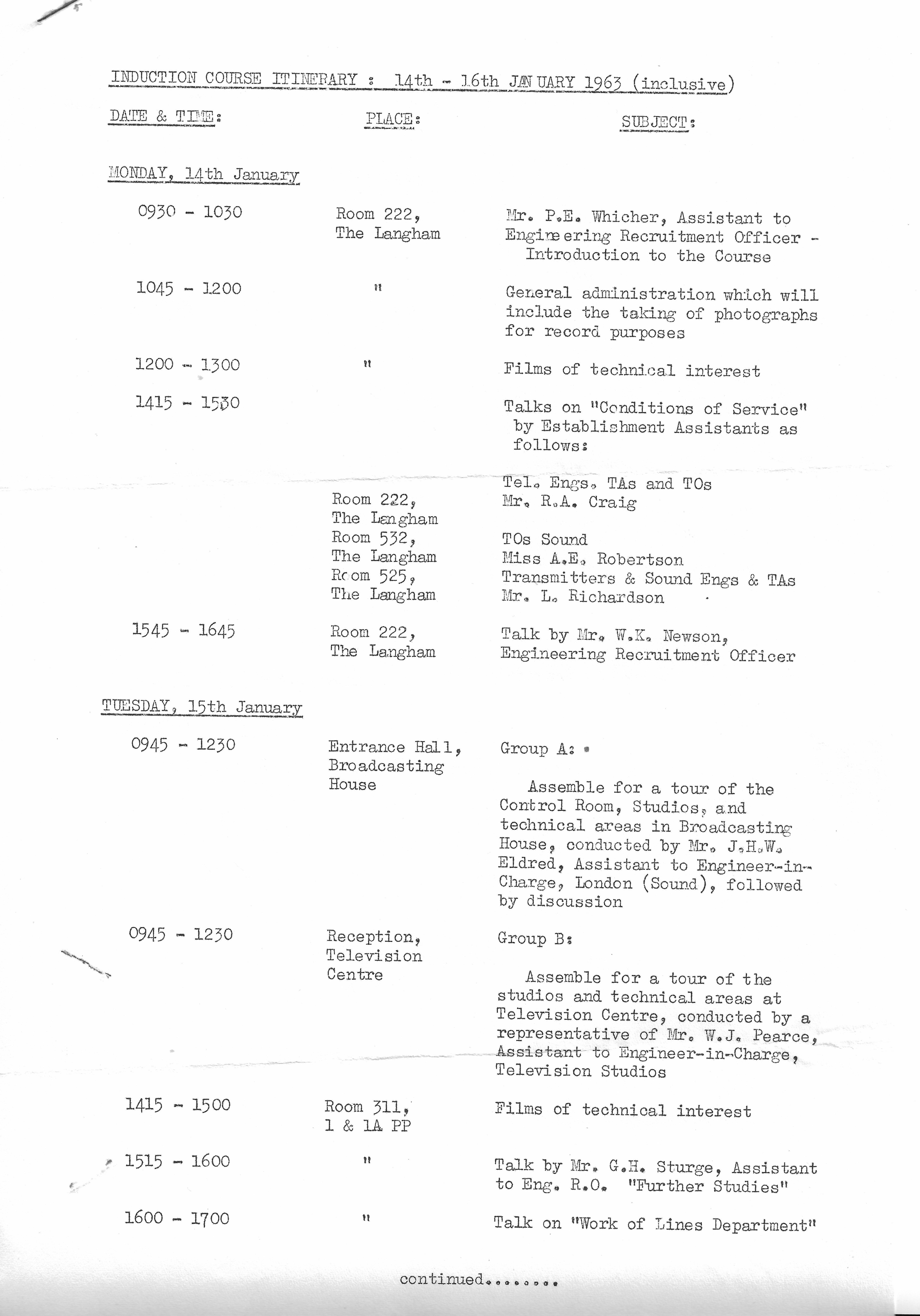

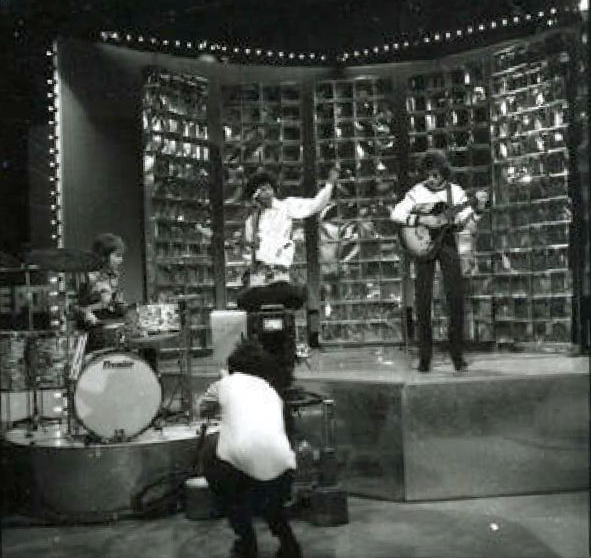

photo taken by one of Jimi Hendrix’ entourage

It was very strange that whenever we went to get Cameras out of Television Centre technical storerooms (just to the side of each studio), there would often be one camera that was missing their viewfinder hood! These hoods clipped onto the rear of the camera and shielded the viewfinder monitor from the glare of the studio lights, and could be moved up and down to provide better shielding as needed. Every camera needed one – so why were the viewfinder hoods missing? It was a mystery! Some cameramen just taped a piece of card to project beyond the end of the camera, but this was usually unsatisfactory. So one of the jobs that I found myself to do was to manufacture replacement Viewfinder hoods out of card. It was usually possible to find or scrounge card, tape, split pins and other bits and bobs to make a hood that would fit into the slots at the back of the camera and would allow some movement up and down.

Another mystery was one Saturday we came in to do TW3 in TC2 and found that Camera 2 was missing. Just gone from the stores. Its pedestal was still there, its Camara Control Unit was still in Racks, but the camera had just disappeared. We looked everywhere, talked to Maintenance and Engineering but no one knew where it had gone. We even looked under the (wooden) audience rostrum – no joy!

1965 was an interesting year, as I spent a six-month stint on Vision Control – which I really liked. I was Vision Control Operator on the last ever episode of “Compact” (“Journey’s End”, TX date 30th July 1965). I remember Carmen Silvera packing up her desk as part of the end sequence.

The Vision Control Operator sat in the Lighting and Vision Control Gallery with the Lighting Supervisor (later, the role became TM1).

On the Stagger Through, the VC operator did absolutely nothing. In fact, this was in the Job Description (not simply dossing about). All the controls were put into the middle of their travel at the start of the Stagger, and then left completely alone. The idea was that the senior lighting engineer (or TM1 as they later became) should light the scene such that the images from each camera matched – one angle was not hopelessly in shadow, for example.

Then, on the first run through, the Vision Control operator could start tweaking the controls a little – but again, the main emphasis was that the lighting engineer should balance the lighting. Most programmes at this time allowed for a stagger and two run throughs, so on the second run through the VC operator would start to tweak a bit more.

Then came Transmission! The Vision Control operator had a control for each camera (and the spare) so that was six controls in TC3 and TC4. Each control was on a quadrant, forward and back, which opened or closed the iris on the lens – this iris was driven from a motor mounted in the centre of the lens turret on all the Image Orthicons of the time (Marconi Mk III and Marconi Mk IV, EMI 203 and Pye Mk Vs.). The controls could be rotated – this adjusted the black level. And by pressing on the knob, the picture of that camera was sent to a preview monitor. As all the monitors had slightly different characteristics, this preview monitor was used to “eyeball” the picture match from camera to camera. Anyway, the Vision Control operator had a monitor for each camera, next to which was mounted a vertical oscilloscope on which was displayed a compressed trace of the picture waveform. The idea was that the operator checked the waveform for the black level – black in the picture should be just above, sync level (giving a “pedestal”), and then check for gain – make sure that there was no clipping of the whites in the picture. These controls were very roughly analogous to “brightness” and “contrast” in the picture. Above each quadrant control on the desk was a rotary control for the gamma correction – change the relative amplification of parts of the waveform – stretch the backs, compress the whites, that sort of thing. The idea was to check the picture for waveform “quality” and then preview the picture on the standard preview monitor to check that the perceived picture quality from camera 1 (let’s say) matched the picture quality from camera 2 (let’s say). Of course, picture quality on the preview monitor was most essential, so part of line-up was to put the test image (white and black rectangles and lines, generated electronically by PLUGE (Picture Line Up Generating Equipment)) on the monitors and check the peak white output using a light meter (can’t remember any settings!).

There were also similar controls for 2 VT machines and 2 TK machines (although picture matching to a film insert was a losing bet – the gamma characteristics and so on made it just about impossible ever to match Black and White film inserts to the studio pictures.

So, 6 cameras, 2 VTs, 2 TKs – 10 main controls and gamma correction – and two hands, constantly matching outputs.

I used to finish a programme absolutely drenched with sweat, trying to match these disparate sources to make sure that there was no obvious technical difference in picture quality as the Vision Mixer cut the shots.

And then it was back to the Studio Crews as a Dolly Operator. I worked on two serial programmes at Riverside later on in 1965.

The first episode of “Mogul” – a drama series telling the stories of the personalities involved in running the oil company around which the series revolved – was broadcast in July 1965. I worked on many episodes of the first series. After this first series, the show was renamed “The Troubleshooters” and had a somewhat different title sequence.

The other show, “The Newcomers”, was a soap opera, first broadcast in October 1965. A light industrial manufacturing company called Eden Brothers relocates to a rural location, The Coopers, a London family whose breadwinner works in the factory, move to a housing estate in the fictional country town of Angleton. The soap opera was broadcast as two half-hour episodes a week. I worked on some of the early in the first series of programmes.

Some programmes have as much an effect on the people who work on it as they do on the audience who watch it. One such programme was “The Idiot” (1966). This was an adaptation by Leo Lehmann of the novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky. I was absorbed by this production. The first episode was recorded on 8th December 1965 (from Riverside 1) and transmitted on 11th January 1966. More about this, and other stories from my time at the BBC are scattered throughout the Tech Ops web site.

Early in 1966 I enquired whether I could take three weeks annual leave in one go: the answer was “yes” so I planned an adventure with my friend Keith – to go to Rome and back. The car was an Austin A30. Rod operated clutch, Conventional hydraulic cylinders for the front brakes, to the front, but only one cylinder for the rear brakes, with a mechanical linkage from this to both rear drums. The car had severe understeer – it seemed that you needed to start to turn into a roundabout some time before you reached it! My A30 started with trafficators, but these got broken off by pedestrians rushing past to cross the road on Shepherd’s Bush Green (driver’s side trafficator, certainly!). It was originally grey, but I spray painted it bright blue – in the open air, using a vacuum clearer spray gun (a fitment on the “exhaust” of the vacuum cleaner – popular at the time). I also covered the “dashboard” with walnut Fablon and installed large bright orange flashers. These certainly stood out on the blue body.

So we went across Belgium, Southern Germany and Switzerland and across the Julier pass (as the St Gotthard was shut) to Italy.

Down into Bologna and through Firenze and then to Rome, which we reached on Easter Day (a nice hot day, we were able to dry our rain-soak tent in the afternoon). Then back up through Northeast Italy, the South of France – camping at Juan Les Pins – and then back to Calais via Le Puy. Of course, there were lots of incidents on the way, and we arrived back at Charing in Kent with three burnt-out exhaust valves!

It was exhilarating to work on live shows such as “Softly Softly” that pulled in audiences of some 18 million a week. It was exhilarating to work on shows where almost anything could happen, like “Tonight” or where the programme had some “resonance” with the audience, like That was The Week That was” – I worked on the second series. Some of the schools programmes could be quite a drag to work on, and technically difficult – often there would be a caption on a substantial caption stand, and we would have to track into (or out of_ the picture – not easy, as the amount of movement needed was often quite small and the peds were quite weight items to shift about. But then we also got the opportunity to work with some of the best comedians – the only time I saw a crew as a whole laugh uncontrollably was when in the first rehearsal we saw “The Sinking of the Woolwich Ferry” as part of Michael Bentine’s “It’s a Square World”.

Another series I worked on was “Sykes and a …” In this particular episode, the main set – the Sykes living room – was mounted partly on a rostrum. The Audience left corner of the set was supported on an hydraulic jack, and for all the rehearsal time – and audience entrance – this was screen off with a large black sheet or blanket, so it looked as if the set was just elevated on a rostrum, the front door of the house was round to the side of this set, and I was on a camera looking directly at the door – Chalky was to come to the door and ring the bell, and I had a shot of the interaction between Eric Sykes and Chalky. At this time, we wore quite formal clothes, so I was wearing a nice bright white shirt and tie. It turned out that my shirt could be seen through the front window of the living room (as this was at the back of the set, as was I). No black (crew) T-shirts in those days! I had to get my Jacket from the crew room, and do the show in jacket, shirt and tie. As the story unfolded, on cue the hydraulic jack had to exhaust quickly and so the front corner of the set would tip down as if there was a sink hole. This was done for the first time on transmission – to VT. “Retake!” So the jack had to be pumped up again. The audience now had to be primed – they had seen the visual joke, and now had to pretend that they were seeing it for the first time. It was Ok this second time, but the audience reaction was muted compared to the first take.

Television Centre was undoubtedly the best place to work – it had all the facilities, including the technical stores – where we had to go the get special lenses, special this and that – and camera tape. I was working in Television Centre on the day of the 1966 General Election (although not in the studio). I was sent to Stores to get Camera Tape: you normally only got one reel at a time – two if you were very lucky. The Stores attendant must have thought I was from TC4 (the General Election studio) and said, “do you want a box?” yes, OF COURSE! That box of camera tape lasted me years…

Lime Grove was a maze of a place – strange to through fire doors and walk across the fire escape to get to the canteen! There were two lifts to studios D and E, and the one furthest from the entrance was a really old affair. It could easily be stopped by jumping up and down. I saw the fascinating Mechau telecine machines there.

Working at Riverside was nice, especially in Summer when someone would be dispatched to a local pub (not always R3) to set up the pie and pints for crew come lunch break. If you didn’t go to the pub, you could go duck hunting on the canteen tables.

At one of the eateries at the BBC Television Centre – and if memory serves it was the BBC Club – offered a salad bar: the salad bar charged one price for a plateful of salad. The trick was to get some four good sized lettuce leaves, put them put them on the plate with the stalks pointing into the centre of the plate, and weigh these down with a pork pie (or something like that) so the edges of the leaves overlapped the edge of the plate – so then you could pile your plate up with almost double the amount of salad – and it was still the same price!

The BBC Club was the place to go if we were “stood down” when working in Presentation: nearly everyone did three to six months in either Pres A (which did the Weather) or in Pres B (which did, amongst other things, Late Night Line Up (LNLU)). I was lucky enough to get sent to Pres B. The two presentation studios had been designed for use by in-vision programme announcers – a feature of early television (and parodied to deadly effect in Victoria Woods’ show), but by the early 1960s these announcers had gone, replaced by a simple voice-overs from the Continuity Studio behind the Pres studios. On one occasion, the continuity announce was sitting in Network Control for BBC 2 watching the film being transmitted that evening – when the film broke in the Telecine machine. He had to rush out of the Network Control gallery, round to the Continuity Studio, fade up the mike and apologise. You could hear the heavy breathing.

In Pres B we did a forerunner of the “Old Gray Whistle Test”, LNLU and other bits and pieces. But one afternoon we were told that we were not going to be needed – there was no programme scheduled for Pres B – “but stay in contact…” So the camera and sound crew trooped down to the BBC Club. Quite some time later, we got a phone call – you are needed now, something’s come up etc. We hurried up to Pres B. Dunno what the programme was or what it looked like – I had had at least 4 pints of beer…

I sometimes had a huge glass of whisky and ginger when working in Pres B. The LNLU directors usually invited the technical crew down to LNLU hospitality after the show (and while waiting for cars to take us home…). The booze was free, no one was counting… It was interesting to speak with Kenneth Williams (very interested in Roman History) and many other stars or notable characters – including Malvina Reynolds (“Little Boxes”). Eric Thompson had read a poem on LNLU, and I was so interested in it I asked him about it in Hospitlity afterwards. He promised to send me a copy – which he did! “Bagpipe Music” bu Louis MacNiece.

Presentation worked the AP shift system – working Saturday, Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, Monday, Wednesday in a fortnight. It derived from the days when a programme would be transmitted on the weekend, and then get repeated in the later part of the week – a complete repeat (no telerecording). It was the best shift pattern I have come across.

After the rotation to Presentation, it was back to the studio crews.

When the studio broke for an evening meal, the canteens offered a very restricted range of food, and at Television Centre it usually ended up being pork pie, chips and beans with yoghurt for pudding. One thing we all did at the evening meal was to collect a handful of wrapped sugar cubes supplied ostensibly for tea and coffee. We would then suck on these during the rest of the evening, during rehearsal or live transmission to keep the energy levels up.

There were many incidents that stick in my mind – two, especially, from “Softly Softly”. At this time, each series of “Softly Softly” went out live, at 8:10 pm (20:10) on Wednesday evenings -leading up to the then 9 O’clock News. On one programme, there was a set which took up about two thirds of the long side of Studio 3 (TC3). I was on a pedestal camera (Marconi Mk IV) and I had a shot at the far end of this set (that is, furthest from the Gallery): my next shot was at the near end of the set (the Gallery end). I had to go UNDER two camera cables, over two microphone boom cables (riding roughshod over those cables!), get into position, crane up, change lens and focus – in EIGHT seconds! The other incident I was on a rostrum with another camera, and we had various shots – MCU, over-the-shoulder 2-Shot, CU, Medium Wide shot – with two actors. The cutting between us was very quick – so quick, in fact, that there was no time to look at the cue cards. I had to memorise the complete sequence – with just two normal speed run-throughs! No one complained, no retakes (for overseas sales) so I guess it was OK.

In every job there are things that you don’t like. For me, the principal dislike was the dust on the cables that seemed to bite into your hands as you figure-of-eighted the camera cables. Hated derigging the PA after an audience show, and in particular coiling up all the various cables. But one thing that began to get to me was all the hanging around waiting for things to happen.

It must have been late 1966 or early 1967 that I had my yearly appraisal with H.T.O.Tel.S. At this interview, I was told that I was a deep thinker but that my reactions were not fast enough for someone who should be working as a Technical Operator in the Studios. This was devastating at the time. It seemed to me to be clear that I was unlikely to get any advancement on the Studio Crews if people thought my reactions were slow – no one can afford that in live Television! One possible avenue was certainly open – a transfer to Engineering – to become a Technical Assistant (TA) rather than a Technical Operator (TO). To do that, I would need additional qualifications: City and Guilds offered courses and examinations which were suitable – Telecommunications Technicians’ Certificate B. So I studied Mathematics, Principles of Telecommunications and Radio and Line Transmission (failed that last one). Doing this course, I found the mathematics part of it very easy.

About this time, John Henshall brought a problem to the crew: he had got it from crew 14. “Two cylinders of equal diameter meet at right angles. What is the volume common to both?”. The correct way to solve this is by calculus, but I tried a method by making up a model and using Archimedes’ principle, immersing this in water. The model had four faces for which the edges were sine curves.

I sent my solution to the person who had set the problem. Mr. Mansfield of the Nuffield Foundation Mathematics Teaching Project: he wrote back a very encouraging letter “your calculations fitted your measurements better than you claim!”

Then one day I was sitting on a rostrum on the set of a “Softly Softly” stagger-through and the thought came to me – that I could go to college and train to be a teacher. This picked up on one of the threads that I had thought about before I took “A” levels (and what had led me to the languages side of things), and it seemed natural, as I loved explaining this to people. So, on the next day off, I set about applying for Teacher Training to several places, and one college – C. F. Mott College of Education, Prescot, near Liverpool (Prescot at that time the home of BICC cables) – offered me an interview. I went up the night before, thinking that I would have a quick look round the city of Liverpool before going to the interview. Next morning, I went down to Pier Head: I had my camera with me as I thought that I would at least have some photos of Liverpool. As I walked around, I did not take any photos at all because I was so absolutely certain that I would get my place and that Liverpool would be where I would be living. Liverpool was a city that was so vibrant, so alive at that time.

When I went for the interview for the College in the afternoon, I showed the problem and my solution to the Mr. Leddy, the tutor for mathematics: he was intrigued: I was accepted. So I have to thank John Henshall for helping bump-start my subsequent career!

TOTP on the 18 May 1967 was my very last programme as a TO. This edition included the Jimi Hendrix Experience with “The Wind Cries Mary”. I had a 12” lens on the turret – big old long focus lens. The last group on this edition of TOTP was the Tremoloes with “Silence is Golden”. The Mole, moving across in front of me to get ready for the final wide shot from the right-hand side of the set, got its cable trapped round my ped, with the result that my very last shot ever on TV, a CU on the lead singer on the 12” lens, was shaky.

After the BBC…

After one year at C. F. Mott C of E I was enrolled in a three year B.Ed (Hons) degree course at Liverpool University (Mathematics and Psychology). On graduation I went to Ashmead School, Reading, and taught Mathematics and Computer Studies for some 13.5 years. I set up the school’s “A” level Computer Studies course. Wrote the script and lyrics for three musicals, took 130 boys to Weston-Super-Mare for a day trip each year for three years or so, part authored a published school pack on “Money Matters” – and did a part time M.A. at Reading University (and had a journal article published). In 1985, Sir Keith Joseph (Education) said that teachers were not working hard enough – together with some 500 teachers from Berkshire I left teaching.

I went to work for Paul Whitehouse (a son of Mary Whitehouse – shared her determination if not her morals) at TSL Communications – and company at the leading edge of networking. We got taken over by Retix, a US company involved in networking protocols – we designed a high-speed Ethernet Bridge. In 1990, eight of us, including Paul, formed our own company “Network Managers” supplying both kits and complete product for the management of network hubs, routers and bridges using any of the then existing management protocols: a start-up company in software – we worked ridiculous hours (more than once, 36 hours straight off) and did things in incredibly compressed timescales. We sold this company to Microsoft late 1995, but then Microsoft killed the product.

After a couple of years working as Quality Manager (as part of which job I selected an appropriate software configuration product) and Author for a software company located directly above the Angel tube station in London, and a spell working for a year 2000 company where I project-managed the translation of the PC product into Japanese, I wrote off to Continuus Software Configuration when the year 2000 company collapsed. Continuus were recruiting – I got a job as senior consultant. Continuus were almost immediately taken over by Telelogic, whose portfolio included Requirements Management. Certainly for me the job I had for the last 10 working years was the best, most enjoyable and satisfying job I ever had – troubleshooting and consultancy on software change and configuration management across the UK and Europe. In my last year, Telelogic got taken over by IBM (and because IBM give long service awards (10 years) to people if they had that length of service including that of companies they had taken over, I received a long service award from IBM!)

So my career started at the BBC and ended at IBM.