Alec Bray

Are the rules of capturing and editing moving pictures changing?

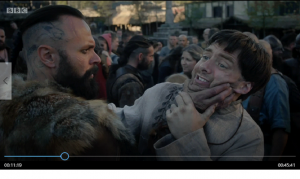

In the sub-GoT programme “The Last Kingdom ” series 2 episode 1 there was a “reverse cut” (as I used to know it) or a crossing of the line that jerked me out of my seat!

(Click on the picture below to see a larger or clearer version of this picture:

Click the “X” button (top right) to close the newly opened picture.)

… and it is badly lit …

I was recently on childcare duty, and the grandsons (7 and 4 years old) were watching a program on the Disney channel – it was an animation of some sort but I did not note the name of the programme at the time.

Well, the line was crossed IN AN ANIMATION! The man and the woman swapped sides as they spoke. I can understand it if the line is crossed on a live action sequence, if there is real difficulty with the camera positioning: but there is no excuse for it in animations – unless the grammar of cinematography is changing.

The same programme featured a “dolly zoom” (US term) or a track and zoom: the girl (back view) was looking out of a castle window; she remained the same size, but the background expanded – nice and easy to do in the animation, of course.

Onto sound: Tasmin Grieg on “Top Gear” (Sunday 19th March 2017) said that when playing Debbie Aldridge in “The Archers” she would stand on a chair if she was meant to be driving the Combine Harvester in order to get the right sound perspective! Way back in the 1960s, on my brief sojourn on the sound part of a crew – trained in everything, of course, in those days – one of the lessons drilled into me was the importance of sound perspective. That’s one of the lessons that has always stayed with me.

Graeme Wall

God that was awful! The reverse cut was pretty bad too…

Patrick Heigham

I wonder if today’s ‘directors’ think that the viewers can cope with a 180 change of angle, and realise that they are looking at the two-shot from the other side.

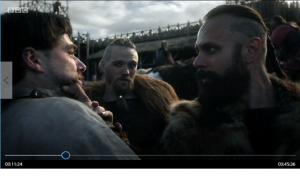

In the second frame, there is a third character shown, so his POV is of the first frame. Probably acceptable.

This would have been better displayed as a two-shot over the shoulders of the two contestants, and keeping the camera the same side as the line between the noses. (At least, that’s what we were taught!)

Why doesn’t the DOP query the set-up these days?

Dolly Zoom:

Yes, I have experienced this visual enhancement. It’s very clever – a tracking shot varies

the perspective of the set. A zoom merely enlarges the view, and does not change the relationship between the foreground and background image.

Tracking and zooming at the same time is a wonderful method of reducing the

background whilst maintaining the image of the foreground artiste to be the same size.

Takes a bit of expertise to get the motion synchronised!

Sound Perspective:

Don’t get me going on that: it would need a huge download!

Alasdair Lawrance

My bête noire is the framing of the over-the-shoulder 2shot. In 4:3 Academy format having the shoulder on the left and the ‘nose line’ more or less vertical in the middle of the frame is very often almost right. When in 16:9 it leaves a load of empty space right of frame. Seems to be mostly on stuff like eg “The Big Bang Theory”. (Note: It’s a programme I only watch for the outstanding acting talent of Ms. Kaley Cuoco, playing ‘Penny’).

Roger Bunce

The general rule is, that if the viewer notices the cut, then it’s a bad cut. If the cut makes the viewer jump, then it’s an extremely bad cut – unless you are deliberately trying to make the viewer jump.

In the two frames shown above, the camera positions are about 180 degrees apart, which means that. of course they’ve Crossed The Line! It’s impossible for two camera positions to be MORE that 180 degrees apart – they’d be getting closer together again! However, the introduction of the third character in the second shot creates new eyelines.

Moreover, two other rules have been broken. The two principle characters have ‘Jumped Frame’, i.e. they’ve moved to opposite sides of the image, instantaneously reversing the viewer’s sense of geography. Also, the cut is between two 2-shots which are virtually the same size, which would create a ‘jump’ even if the camera positions were close together. If the first shot had been a little wider, and the second had been much closer, i.e the two combatants were just defocussed profiles at the edge of frame, putting the emphasis onto the central character – then the cut would probably have worked. (I’m having a moment of deja vu, here. Have we had a very similar conversation before?)

Assuming it was the same camera operator was taking both shots, he should have known how to make it work. Equally, the Director should have thought it through at the scripting/storyboard stage. Sadly, these days, there is often no shooting script until the edit, which is too late. Those involved in the actual shoot have no idea of the timing of the cutting points.

You’d never have had this problem in a multi-camera situation, of course, because the two cameras would be in each others shots!

As for sound perspective, that was largely scuppered when they stopped using booms, and went for personal mikes – much the same reason as the inaudible dialogue.

Alec Bray

…I’m having a moment of deja vu, here…

We have – of course – had a very similar conversation before. See Crossing the Line – Again

see also Director training.

The reason to raise it again is just that I’ve noticed this “crossing the line” more and more in recent productions – and I was amazed to see it in an animation. So I began to wonder if this is becoming part of a new way of telling stories in pictures. And , of course, apologies to Roger – I should have mentioned his “dolly zoom” (Track in and Zoom out) in “Cameraman- The Movie” which predates the Disney version by ….. years! (and, famously, in “Jaws” (Graeme Wall)).

The 180 degree change of camera position is great if, for example, the camera is tracking forward following two people down a path, and then switches to a front view, the camera tracking back as the people walk towards the camera. But in many cases I have noticed, there is no motivation for the change of viewpoint.

As an aside here – there were times (in my short time at the Beeb, I confess) when the camera person would ask the director what was the motivation for a particular action. Not often, mind, but just occasionally (or is the old fallible memory even older and more fallible?)

So: to things visual that are done now but were not acceptable in my time.

1. Cutting between just about identical shots.

2. MCU with character looking right and on right hand third of frame (and looking left on left hand third of frame)

3. The old grammar was that if a character went from one room to another, the cut between the two scenes would happen as the character was halfway through the door. This does not happen now: there are often “Jump cuts” between two dissimilar scenes, leaving the viewer to imagine the intervening bits.

and so on …

Geoff Fletcher

The rules of composition/framing and acceptable cuts which we were all taught worked back then and are still valid today. Any cut which causes the viewer to sit up and take notice – where this is not intentional – is a bad cut.

Having said that, I think there is a tendency today among some directors to try to re-invent the wheel, or else it is just plain ignorance and/or lack of training/appreciation of their craft. Reg Poulter once said to me that you have to know the rules regarding cutting and framing before you can intentionally break them for effect. Good advice – then and now!

Tony Nuttall

Alec, I do think you need to “get with the programme”. Some of the new more basic techniques you need to understand fully. Firstly with multi camera shooting there is no crossing the line as the line no longer exists!

The thing that you probably remember as a Close Up or CU is now no longer based around the face but is now centred on the Ear ‘Ole! All cameras must be mounted on a Dildo Head. This is a new type of camera mount that, when used on a static shot of an artist or presenter, HAS to move left and right, up and down but essentially without any motivation.

The other area that is again now mandatory is that which you may have referred to as an eye line, into a camera lens, is now adjusted to some 30 or 40 degrees to the left or right of what you would have called in the old days an eye line. This has the effect of engaging the viewer so he/she now no longer knows who is talking to who! This creates more interest in the programme as the viewer has to guess if there is a third party involved in the material being shot. A kind of mystery invisible artist/presenter is created!

One final area that many people on the Tech Ops list have not grasped is that all sound must move up and down at all times not in relation to each other i.e. the sound effects, dialogue being spoken or the essential background music. Sound levels should not adhere to the parameters once set by the Transmitter, the old Simultaneous Broadcast system and the PPM. Loudness is now King. It can be described a bit like Brexit as being Red, White and Blue Sound.

The variable sound levels do have a distinct advantage in the fact that us more Senior Tech Ops types do receive considerable therapy as we use our remotes. They do help our Arthritis with constant exercise combined with stimulation of the mind! This again creates more interest in the programme from the participating viewer.

Roger Bunce

In the unlikely event that anyone has taken my advice and watched “The Worst Witch” on CBBC, they might have also seen the programme that follows it: “Top Class”, with Susan Calman. My Grandson really enjoys it. It is a standard team quiz game for schools, laid out like “University Challenge” or “Top of the Form” – the sort of programme we’ve been making for years. What could possibly go wrong? They have an interlude where a teacher answers questions from a centre spot. At this point, the eye-lines are all over the place! It’s impossible to know who is looking at whom. How The Hell Can They Get That Wrong? It’s a multi-camera, as-live, studio show. All the cameras can see one another. The Director and Vision Mixer can see the cuts as they happen, live. There’s absolutely no excuse. It can only be sheer bloody stupidity! I wonder if it’s made at Salford?

The problem with dramas, I suspect, is that they are shooting single-camera (or a couple of cameras) film style, but the Directors are not planning their shooting scripts tightly enough in advance. They are postponing decisions until the edit – the ‘sort it out in post’ mentality. Consequently, the cameraman/men on the shoot don’t know where the cutting points will be. Knowing whether you’ve crossed the line, or not, can be as critical as knowing whether they’ll cut to you before, or after, a particular head turn. I suspect this has come about because of a reversal in the relative costs of performance and post-production. Once upon a time, post-production was incredibly expensive (razor blades cutting video tape, etc.) so you tried to get everything right at the performance stage. Now, post-production is incredibly cheap (anyone with a decent laptop can do the edit in their bedroom), while the performance stage is the expensive bit. So, there’s a tendency to rush the performance, in the innocent belief that all problems can be sorted out in the edit.

I have occasionally asked, “What is my motivation for this move?” Sometimes it is a serious question, i.e. at what point do you want me to start the move: on the cut; on the artist’s turn; on the change of mood; etc. Sometimes it is a politely sarcastic (if that’s possible) way of suggesting that the intended move is silly and completely unnecessary and, unless the Director can give me a damn good reason for it, I don’t see why I should put down my cup of coffee!

Getting philosophical, for a moment – I think that television grammar originated with 405-line, fuzzy pictures on small screens. The resolution was too poor to stay on the wide shot for too long. You had to cut in to close ups, if you wanted see facial expressions, but, at the same time, you had to preserve the viewers understanding of the wider geography, without constantly cutting wide. Thus rules about eye-lines, looking room, etc. became necessary. Such rules were less critical in feature films, where the big screen allowed greater use of wide shots, and cinema audiences could select which part of the screen they wanted to look at. The poorer clarity of TV pictures made it necessary for the camera to do more of the selection. However, tele screens are now getting bigger, with higher resolution. Sooner or later they will cover the whole living room wall. (Let’s hope the wobblyvision fad will have passed by then, otherwise there will be a lot of vomit hitting a lot of carpets!) By this point, most of the rules may have lapsed. It will be possible to show whole scenes in one wide shot, and viewers will watch them as they would watch a theatrical performance – the only cuts being between scenes. However, while domestic TVs are getting larger, people are also watching video on their dinky little, toy-town mobile phones. On those small screens, the grammar becomes important again. So, which way the future?