…follows on from Spot the Errors …

Dave Mundy

As a mere sound man I think that the studio fixed lenses in a 4-way turret went something like 35, 24, 18, and 12mm. focal length, the 5th. hole on the green EMI cameras was blanked off.

Peter Combes

The numbers are familiar, but are they not the acceptance angles, in degrees?

Geoff Fletcher

In my days at the BBC the fixed lenses on turrets were, in degrees, 35, 24,16 and 9.

The EMI cameras had a blanking plate in the fifth lens position – I never saw it used for a lens.

Pyes and Marconis only had positionsfor four lenses. On dramas, the Relief Mainly Cameras or DO3 often had a selection of other lenses at hand and was responsible for putting them on in place of one of the standard lenses as required. Care had to be taken with this, as one of the longer lenses could only be put on opposite the 35 degree, not adjacent to it, as the end of it would be in shot on the 35 if it was used in the same scene as the long lens. The non standard lens would bugger up the head balance too, as it was usually heavier than the one it replaced. At the end of the scene the non standard lens was removed and the original put back, unless you forgot, in which case the cameraman let you know about it in no uncertain terms!

You made up a list of when and what on the staggers and run throughs and things usually went quite smoothly. With the advent of colour and universal zooms the practise became redundant of course.

In focal lengths, I think the lenses were 2 inch, 3 inch, 5 inch and 8 inch, but I always thought of them in degrees.

Alasdair Lawrance

The problem with fitting a long lens next to a wide angle one was at least partly resolved by the conical turret on the Pye Mk V. Similar to a microscope, and that was also something that Pye/Phillips made.

Peter Cook

The 40" lens was frequently required on OBs. Even with the conical turret of a Pye Mk6 it had to be placed in position 3, opposite the wide angle which was position 1, otherwise it would be in wide shots. I have a suspicion that the 3" was the widest that could be used with a 40". but 3", 5", 8" and 12" or 16" would not have been uncommon with fixed camera positions. The advent of zooms made life a lot easier for the cameramen even if not for sound. However there was not a lot of drama or boom work; I remember that booms and boom ops were sometimes brought in from studios.

Geoff Hawkes

The standard turret was 9, 16, 24 and 35 but occasionally the 35 was replaced with a 50 from stores if the production required it.

Dave Plowman

It is really a sound man’s definition – degrees of view rather than focal length. The reason being that different types of cameras required a different focal length lens for a given angle of view. As a sound type we weren’t much interested in that – only what the shot would likely to be by glancing at the camera, before the days of monitors everywhere.

Pat Heigham

A discourse on TV Technology, started by myself in order to help a guy writing his thesis, with help from various people who worked in different depts (see http://tech-ops.co.uk/next/2016/03/tv-technology-over-the-years-bbc-practice/) produced the following:

“… In TV, the lenses were referred to by the horizontal angle in degrees across the screen. This was different to film cameras for the cinema, which are named by the focal length in mm. TV camera lenses were also referred to by their focal length in inches. On the Marconi Mk III these were 2”, 3”, 5” and 8”….

(Other focal length lenses had to be booked from Stores and mounted on the camera in place of one of the standard lenses)….”

My memory is hazy, but when plotting camera positions at the pre-planning stage, there were stencils available for cameras/booms etc, so would there have been protractors for the various lens ‘angles’ in degrees to set the field of view at the outset (before zooms, I guess).

Zooms were a pain for the boom ops, as without a monitor, one couldn’t judge the shot size, and therefore the headroom – a glance to see what lens a camera was on, gave us a clue.

Dave Plowman

In the early days of TV there were different types of cameras in use. 3 and 4.5" IO. CPS Emitron. Maybe even Vidicon. They all had different target sizes so would produce a different shot using the same focal length lens. Unlike with feature films of the day, where 35mm was pretty universal.

So for planning etc purposes it made more sense to use angle of view – so only one set of protractors etc needed, regardless of the type of camera that ended up in use. The nuts and bolts of which lens produced the correct angle of view for a particular camera was something a director etc need not worry about.

Geoff Fletcher

On having a re-think… so – it was 35o (2"), 24 o (3"), 16 o (5"), and 9 o (8"). [There were] replacement lenses as required, however. I remember doing the job on occasions.

An amusing incident I was involved in occurred on “Champion House” when I was doing camera 4 with Crew 14. There was a scene which took place at a party or some such do on, I think, a boat, and I had a long sequence of fast lens changes. I finally managed to get it right on the last run before tea break on recording day, and over tea I expressed my relief at having done so rather too much. After tea, on the final run and on this sequence, I was rattling along and keeping up with the lens changes until I swung from my 24 o to the 16 o and the shot stayed the same. I swung again and found myself on the 9 o, Back and forward I went, having lost it completely, trying to find the correct lens. Everything ground to a halt and I was left standing there red faced and somewhat perplexed. Dave Mutton, grinning from ear to ear, told me to have a look at my turret. Yes – you’ve guessed it – there were two 24 o s on it, the 16 o having been replaced by the crew joker (nameless to protect the guilty). Dave pointed out that it was an object lesson to always check your lenses after any break involving leaving the studio. I never forgot to do so after that. You live and learn.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

Pat Heigham

A story against myself…

TC2 – a schools programme.

I was tracking the great Jim Atkinson on a motorised Vinten. We had to start from a far corner of the studio and track in on a curving path to hit a ladder which then ran up and down a series of set fronts.

Perfect on rehearsal, but on the take, I blew it and finished up two feet further back from the tracking line. No zooms to adjust the frame, so I got a severe wigging from Jim.

Sound beckoned!

Jim taught me camerawork in half-an-hour flat. I’ve done OK with my private photography, thanks! But panning and tilting and zooming all at the same time is very much an acquired skill – not to mention focussing as well!

John Nottage

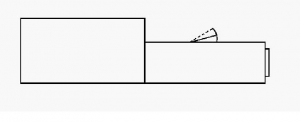

All this talk of lens angles and how zooms made the boom ops job more difficult… I’m sure I remember an early zoom lens (Philips?) that had a plastic do-dad on the top which moved up and down with the zoom, giving an approximation of the zoom angle of view. It didn’t make it to any other zooms that I know of, so it can’t have been a success.

I’ve done very much not to scale sketch of what I remember. As I think about it, I’m wondering if what I remember was actually on the top of the camera, not the lens… I’m sure it was on a PC60(?) or something.

Chris Woolf

Oh yes, it existed.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

Geoff Fletcher

The Peto-Scott cameras in Pres B in the late 1960s had a yellow "coxcomb" on top which raised or lowered as you zoomed in and out. Don’t think it would be of much help to a boom op though.

Mike Giles

We had very similar cameras in Bristol with those same yellow angle indicators on the top. But the indicators were all broken by the time the cameras reached us ~ bar one which broke soon after arrival! Whilst it worked, it gave rise to more amusement than useful information.

Steve Edwards

Regarding Orange Zoom Indicators, Tony Nuttall sent this to me a few years ago:

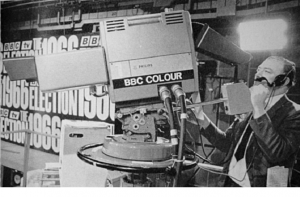

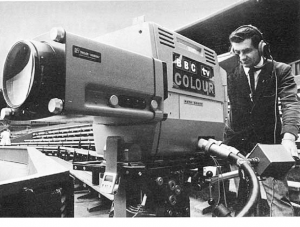

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

You can see the foreground camera is a PC 60 – the Peto Scott badge is visible. It’s a Taylor Hobson Varotal 16 lens – curious whether the zoom indicator was a Peto Scott/Philips component or retro fitted/supplied by lens manufacturer.

The idea was the greater amount of wedge showing the wider the angle of the zoom shot being taken. Small amount of wedge, tight angle. Soon got removed and replaced with a blanking plate on the PC60

A Long Shot (sorry for the pun) but does anyone know who the guys in the picture are?

John Nottage, Chris Eames

Selwyn Cox is on the foreground cam, with Alec Wright on the Pye Mk 6 to his right.

Peter Cook

Selwyn Cox near on colour and Alec Wright on the Pye Mk 6. Trooping the colour circa 1967 when we tested colour alongside monochrome.

Alec Wright and Jack Hayward both wore old style tweed jackets and I was initally fooled by the burnt out face in the photo. Looking again I can see the more portly outline of Alec. I believe that he, unlike Jack, is still with us. You notice the correct rifle mic for the period.

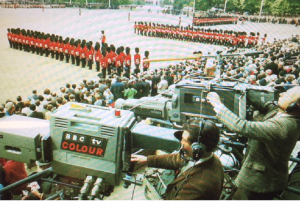

Below is a shot of Selwyn and the same camera a week or so later at Wimbledon.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

John Nottage

I think the mic looks like the old Labor (think that’s the right spelling) gun mic. It was a long metal tube with a sort of grill along the length and a torpedo shaped lump with the mic socket at the back.

However, I don’t remember it having any sort of windshield: that one seems to have some sort of yellow foam cover at one end.

Chris Woolf

The PC60 was a Philips design (1964) which was developed to use a zoom lens from (almost) the outset. The lens angle indicator was integral to the early design, probably ~because~ it was one of the first cameras to enforce the use of a zoom – either a Varotal IX or XVI. The use of zooms avoided the severe problem of colour matching primes.

The Peto-Scott, Pye and (US) Norelco badges were just that – all the cameras were (Dutch) Philips but sold under these names to get round nationalistic sensitivities – something that may become a problem again…

David Deness

Peto-Scott was a British company that was acquired by Philips so they could sell equipment to the BBC when the charter said they had to buy from British Companies.

As a boom operator at the time, it did give a very rough indication even if only wide or narrow view

Alasdair Lawrance

The bigger problem was how to adjust focus – it might’ve involved moving the whole ice-block/tube assembly, which was a bit impractical. Or make new lenses with focus sing elements, I suppose.

Chris Woolf

Adjusting focus could have been done by shifting the turret in relation to the prism/dichroic face. The RCA TK41 used this trick. The turret moved in and out with all the lenses on it, driven by a twist grip on the right hand pan bar. The camera also used a set of relay lenses internally because the back path was so long, and an internal iris. Apparently the optics could not manage anything better than f4. But they did crow about a remote control capping device to allow the engineers to set up black level on the 3 x 3" IO tubes.

Alasdair Lawrance

I remember the zoom indicator – was it Schneider? Angenieux? Don’t think it was Taylor Hobson.

Pat Heigham

I spent a long time thinking about how a ‘do-dad’ could be mounted on the top of a camera zoom – the best idea I came up with was a cone of sticks which would expand and contract with the zoom selection. It would have to have been 3D, thus viewable from any direction.

The problem was solved, I understand when booms were equipped with monitors. I believe they were CRT 9" Phillips? Much easier now that flat screen small monitors are available – but! how many productions employ boom mics these days?

Working freelance to cameramen using Betacam, and having the SQN on an umbilical to the camera, one of my (also ex-BBC) colleagues discovered some unused conductors in the cable weave, and engineered a video feed back to the sound mixer – a small Panasonic 3" monitor could then show what the cameraman was up to!

Dave Plowman

I remember seeing something similar (a ‘do-dad’) on the side of the zoom on earlyMarconi colour cameras. A sort of horizontal V where the ‘legs’ opened and closed. But being part of the zoom, it was not easy on an EMI 2001.

My memory tells me I saw it in a TC studio. Did they ever have PC60 in use there – even as a trial?

I’d thought it was on a Marconi Mk6? The ones that got chucked out of the studios to news, etc. But not sure the indicator was on all of them – may just have been a prototype.

Peter Cook

At Wembley, the OB Roving Eye had available for its Marconi Mk 1b a ‘Zoomar’ lens, which was probably 5:1 or less. As I recall the turret was removed and zoom lens fitted, an operating rod passed through the camera body in place of the turret rotation handle. To zoom, this rod was pushed or pulled and to focus it was rotated. Boom ops could have observed the position of the rod but probably not in the middle of a racecourse!

Graham Maunder

I don’t remember the external zoom indicator but I do remember making a small cut-out boom microphone, placed on my lens hood, that I could lower into my shot to get a reaction from the director! As I recall it had a piece of string attached to it which was in turn attached to a piece of magnetic ‘isobar’ strip from the weather chart, which enabled a swift in and out!

Best time it ever worked was with John Hays on a boom who almost had his boom up in the lights and was still being told ‘just in’!

Happy days.

Roger Bunce

You are referring to the ‘Angenieux Retake Simulation Equipment’, which, when used with a Schneider lens, could also be known as the ‘Schneider Headroom Inhibiting Technique’: very much the camera equivalent of the pre-recorded scaffold poles being dropped in the ring road, or the pretend ‘hair in the gate’ on a film shoot.

Then there was the ‘Always-on-my-Mark’ mark, a camera-tape mark which was struck to the base of your ped, but not to the floor, so that it went everywhere with you: just in case of argument.

Pat Heigham

Talking about artistes marks – I worked on a Stephen Frears film for Thames.

The Lighting Cameraman was Chris Menges (Prince of Darkness) who exposed to such a low level and wide f-stop that if the (largely new cast) didn’t hit their marks, they were out of focus. Many takes!

Nick Ware

Marks or no marks, f11 or f1.2, I only ever had good experiences with Chris Menges. He has an awful lot of Craft Awards, Lifetime Awards, and Oscars to his name, and was/is one of the most highly acclaimed and in-demand of his ilk – both sides of the Atlantic.

I’m proud to have worked with him.

John Howell (Hibou)

The mention of a microscope on the turret reminds me of one of my earliest studio days when I was allowed to do a camera! But it had a microscope on the front, in the lens No. 5 position, I was told not to ‘fiddle’ with anything, in particular not to try changing lens!

Peter Fox

One or two directors would ask for 24° lens on the shot cards for action shots because it "preserved natural perspective". This can work very well on a track, of course, but it made life difficult if not impossible in the hurly burly of ‘as-live’ TV using peds so most cameramen would actually select a 35° in preference. Inevitably there would be the occasional query "Are you on the twenty four?" So you could either nod yes, or change lens, half forward, half back, with a bit of a push-in buried in the the visual whirl. Then carry on as before. The snag with this was that nobody learnt from it, either way.

Dear old Jim Atkinson would argue that actually a fifty was a "natural" lens on the basis that if you were inside a real room you would be close to foreground people and the perspective would be deep. Funnily enough this theory suited his preferred style of in-close, dynamic camerawork.

Roger Bunce

I, too, remember being told that a 24 degree lens gave natural perspective, as seen by the human eye. This led to a general feeling that Jim Atkinson was ‘cheating’ when he used a 35 or even a 50! But they also taught me that lens angle has no effect whatsoever on perspective, which is why you can zoom in and out without any perspective change. Since the later is clearly true, the former must be complete rubbish. It is the distance between lens and subject that affects perspective of mass. (There’s a very good booklet about this sort of stuff.) You’d have to state the shot size, together with lens angle, in order to define the distance.

When I was young, and still trying to understand things, I remember reading that Granny’s old b/w tele was supposed to be positioned such that it subtended an angle of 10 degrees at Granny’s eye (in order not to see the lines). In this case, to give natural perspective from Granny’s position, we should all be using 10 degree lenses! – Except – that TV is only 2-dimemsional. If we want to create a realistic sense of the third dimension, we should be tucked in closer on a wider lens, in order to exaggerate depth. After getting confused by such thoughts, I gave up worrying and just operated like everyone else – as close as I could be without casting shadows or getting into other people’s shots, on whatever lens gave the required shot size. (How did Jim Atkinson keep out of other people’s shots? By doing the whole scene himself!)

Another vague and possibly inaccurate memory. Were the standard turret lens angles chosen to give the standard shot sizes from the same position? That is, if you had a MS on a 24, would swinging in to a 16 give you an MCU, and swinging in to a 9 give you a CU? Or would that have been far too easy and sensible?

Alec Bray

I had to do exactly this on a "Marriage Lines" in R1 – trouble was, it was on the Pye Mk 5 cameras with slow motor driven lens change, and on this occasion the cutting was fast, and I only managed the shots by trying to prefocus as the turret swung round.

Mike Minchin

Yes: that’s why the lens chart was so useful for setting up the zoom shot-boxes.

Nick Ware

A zoom lens merely magnifies the image without altering the perspective unless you move the camera in as the lens widens. A prime lens-change does the same unless you move the camera closer to the subject and user a wider lens, in which case you alter the foreground relative to the background.

Moving the camera in on a wider lens lets the boom get in closer too, whereas zooming in from the same spot doesn’t, for obvious reasons.

That’s perspective from a soundman’s perspective!

Alasdair Lawrance, Roger Bunce

So it doesn’t matter which lens you use, the (apparent) perspective is the same, so long as the shot is the right size?

Zooming out while tracking in (it’s easier to focus that way (“Dolly Zoom”) is a favourite of Spielberg, in "Jaws" for example, it’s an ‘un-natural’ movement.

The headroom is the same, but the boom will be in front of the actor, as well as above. If you were to draw a ray diagram, you will see that the boom has space to drop lower when the camera is closer, on a wider lens (assuming the camera is on eyeline).

Geoff Fletcher

Didn’t Hitchcock use the zoom out track in technique on the shot of Martin Balsam falling backwards down the stairs in “Psycho”?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bieIiX5KLQ

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

Roger Bunce, Chris Woolf

Hitchcock certainly used it in “Vertigo” (1958), up and down the tower. There’s no reference to it being used in Psycho (1960) but it might have been.

Alec Bray

Called the “dolly zoom” in the film industry …

(Click on the pictures below to see larger versions:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

Mike Minchin

The combined zoom-track (retaining something "the same size" throughout) was invented by Alfred Hitchcock, for "Vertigo" – and it cost him a bomb. His version could only be done with a set model, and the studio insisted that everything had to be interlinked. Once set up, it was all automatic, and could be repeated ad lib.

Chris Woolf

No, it wasn’t invented by Alfred Hitchcock. The usual credit for it is Irmin Roberts, the (uncredited) second unit cameraman on “Vertigo”, although the special effects cameraman, John Fulton, sometimes gets mentioned.

I don’t mind Hitchcock getting credit for using the effect, but it is intensely irritating to have history distorted so that the true inventors get missed out, and those with louder voices or more celebrity take the credit. John Logie Baird invented nothing that relates to current TV – Alan Blumlein and Phil Farnsworth have much better claims. Baird was just good at publicity. Dyson didn’t invent the bagless vacuum system – he merely borrowed an idea that had been used for a hundred years in all sorts of industries. Likewise the bladeless fan – Toshiba 1981. Marconi almost certainly had a false claim for radio – Tesla’s is much better – and Thomas Edison was a serial stealer and patent-claimer.

John Nottage

That “track and zoom” reminds me of a drama I worked on back in the late 1960s in TC something.

Large senior cameraman (crew 6 maybe?) on close-up on 8in lens. Suddenly the actor decided on an unscheduled walk towards the camera! Cameraman, camera and ped moved smoothly back to match the motion without a shake or hesitation, maintaining focus all the way. Everyone was most impressed!

Albert Barber

On “Grange Hill” when I took over we tried to keep the lenses to 35 degrees.

Roger Bunce

Then there were endless discussions about how to make a set look cramped and claustrophobic (which, of course, it wasn’t – because it didn’t have a fourth wall!). One school of thought believed that the Wide Shot should be taken from far away on narrow lens. This would foreshorten the depth of the set, making it appear small in one direction, but do nothing about its width and height. The other view was that the Wide Shot should be taken from close in, on a wide lens, because this is where you’d have to be if it really was a cramped, claustrophobic set – but this would make the set look deeper, and therefore bigger. Opinions seemed to waver back and forth between the two ideas. It was only after many years of age and experience that the truth finally dawned on me. If you want a set to look cramped and claustrophobic – DON’T TAKE A WIDE SHOT! Shoot it all in close up. If you really need more than one person it the frame – push them closer together – as they would be – or get the camera closer to the eyeline. Lots of dirty singles are good.

We did a version of "Alice in Wonderland", directed by the wonderful Barry Letts. It was mostly shot against blue-screen (or was it green?), with some delightful inch-to-the-foot scale models as backgrounds. Barry had planned all the wide shots to be taken on a 35 degree lens. But, by now, it was all zoom lenses, and we’d long ago forgotten where we put those lens angle line-up charts. So we had to guess. Barry would frequently ask, "What lens are you on?" Armed with my secret knowledge (that lens angle doesn’t actually affect perspective) I’d answer promptly and decisively, "35 Degrees!", and Barry would be happy. (It must have been about there somewhere, and, anyway, I reserve the right to zoom in and out a bit, to improve the framing.) Some of my more honest companions would begin, "Well, it’s difficult to tell, because we’ve got these zoo . . .", while I found a bit of floor-chalk to throw at them – before they gave the game away!

Barry resorted to mental arithmetic as we lined up each shot. Being slower witted than he was, I resorted to pencil and shot-card. Just once, found that he’d made a mistake. He was out by a factor of two. The camera was twice as far away as it should have been: the depth of the shot was halved. But, by the time my slow-witted brain had worked it out, we were recording. I looked at the shot. I could see the effect. But no one else had noticed, and it was a great shot, so I didn’t say anything. No one was walking towards, or away from, the camera, which is when things become critical.