Background

The crane was first manufactured in the US in 1949 by US Houston Fearless, and was known (naturally) as the Houston “Fearless” Crane. Mole-Richardson (another US company better known for lighting equipment) was licensed to build it in the UK (where it became the “Mole”), but because the crane had started life as a design by the Hollywood-based Motion Picture Research Council, it was also known as the MPRC Crane.

As such, the Mole was, at basis, a motion picture crane. A short-wheelbase dolly had a central pillar (which could be raised) on which was pivoted a counterbalance arm. At one end there was a platform for the cameraman and focus puller (and at a pinch, the director), at the other a large bucket full of lead weights. Weights were added to balance the camera and cameraman.

The Mole Crane went though a number of iterations to adapt it for television use – including a manual version and four-man version – before its final, 3-man, form.

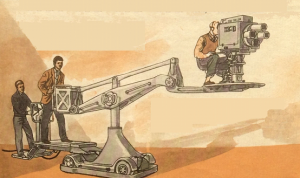

3-man Mole crane with a CPS Emitron camera:

Illustration forwarded by Irvine Brookes, formerly of TV Centre and OBs, from the publication “Readers Digest Junior Omnibus” (1958, The Reader’s Digest Association)

(see also: http://tech-ops.co.uk/next/2013/11/a-whole-mole-page-from-alec-bray)

Mike Giles

I started out in Bristol too and spent many hours fighting with the entirely manual Mole crane, not to mention the awful Mole booms. Their common feature was slack controls – whatever you did with tillers or wheels didn’t stop when you intended and then it probably wouldn’t stay where it was. The only thing truly under control was tracking as it relied solely on the strength of the guy doing the pushing – I can’t imagine a non-motorised crane of that total weight getting past Health and Safety nowadays, but that brings me to an apocryphal story of a guy who had gone on to greater things by the time I got to Bristol. The steering rack broke early on during a live transmission and he spent the rest of the show lifting the back end to steer! It became a test of strength for his successors and whilst it was possible, I wouldn’t have wanted to do it for long!

John Hays

I recall in the early sixties driving the Mole from a precarious seat fixed halfway down the right hand side and it being steered by a tiller from the back. It could also be steered by sitting on the rear platform and putting one’s feet on the tiller! Needless to say a near disaster occurred when a steering wobble developed on a fast track in at the TV Theatre.

Was this the original design of the BBC mole?

PS I worked on sound after that!

Alex Thomas

I joined Tech Ops in summer 1960 and was quickly put onto cables and monitors. (“C and M old boy” was the instruction.)

I progressed to being the fourth man on the mole crane operating the tiller at the back.

The driver sat on a tiny seat at the base of the jib support column. The whole thing was powered by a 110 volt dc supply which came from banks of rotary generators located in the bowels of Lime Grove.

The supply terminated in a Kliegl connector the width of which limited the amperage that could be taken from the socket. So a pup or a soft light could be plugged in to the same socket as the crane but in theory the socket could not be overloaded. For reasons of safety the supply was 55 volts positive and 55 volts negative which meant that in theory at least no one could get a lethal shock.

Any earthing of the crane body must have been down the outer of the camera cable.

Of course, things did go wrong. I remember the cable guards running over the power supply cable and cutting through the pos and neg causing a short circuit which dimmed the soft light on that scene.

The other disaster was on the Garry Halliday kids drama series when the bucket of the 4 man Mole caught on the driver’s hand control and sent the crane fast forward towards the set complete with crew. It smashed into the set but fortunately it was only the dress run and repairs were possible.

Oh happy days!

Hugh Sheppard

On Crew 6, bucket-swinging for Mark Lewis, and with Andy Tallack driving the now-modified 2-man mole, we were working on a “Music for You”, live as usual.

During rehearsals, the director asked for Camera One, Mark on the mole, to do a long traverse between shots for which there wasn’t much time. Starting with the bucket high and the jib at right-angles to the body (with me off the platform) at the end of one shot, we had to motor about forty feet for the next and put Mark high above the orchestra for a close-up on the bassoons. When Mark didn’t quite get there, he called for the mic and explained: “I’m sorry, but my boys can’t make it”.

That was a red-rag to Andy and to me, so we countered with “Oh yes we can”, and the sequence stayed in. Come transmission, Andy shot us backwards when the red light went out, then forwards and to the left and right, while I somehow climbed back on, heaving the bucket down as Andy brought us to a halt. But it had been too much for Mark; losing his footing and with the director shouting “On the bassoons, Mark; on the bassoons” he hung there, slowly spinning and with the camera facing the wrong way. A real ‘Oh my paws and whiskers’ moment, and one I’ll never forget.

When the first TVC studio (TC3) was about to open circa 1960, I was on Crew 9’s Mole crane crew, with the late, great Laurie Duley as senior cameraman. One day a few of us took the familiar trip up Frithville Gardens from Lime Grove on a pre-production mission to test a Mole crane on the brand new studio floor. With Laurie on camera, I was driving – from the side as I remember – when we came to a whirring halt. Whirring because a driving wheel was spinning due to the floor not being level and a non-existent mole crane suspension.

All around us a row broke out between those responsible, which was only resolved when the variation was measured. This turned out to be greater than the depth of the topping, so the sub-floor had to be to blame. While we didn’t realise it at the time, the months of delay were almost certainly hushed up, as I’ve never heard anything about it since.

John Wardle

As far as I remember the studio floors at TC were originally thick linoleum laid on a screed over concrete until we changed to self-levelling resin. When we changed to resin this caused static problems and affected some cameras. The linoleum was always being damaged by the scene boys dragging sets across the floor. The change to resin was after I moved to Technical Investigations so must have been after 1972. I remember doing floor level tests with either a Mole or Heron.

Peter Fox

Sometimes you could get a man in to cut out the damaged bits of lino and Evostick a new patch in, but mostly the repair had to be scheduled for another day. Very annoying because the cuts and scrapes were always exactly where the perfect tracking line lay. At least we didn’t have to put up with static belts and surprise crash zooms back then!

The Mole did have minimal suspension, with very short (hence very stiff) cart springs, either on its axle at the front, or on the steering end, I can’t remember the layout exactly, it was rarely to be seen, unless the mech workshop had one up on their lift.

Remember the dip in R2? It would challenge a motorised Vinten or any dolly for traction and usually need a push to get going again. Used to collect a reasonable puddle after roof challenging cloud bursts too. Wheels spinning in melted blue floor paint. Lovely

Doug Coldwell

The real killer of the lino floors was the overnight floor wash which allowed watery gunge to seep under the lino tiles either at the edges or from a divot. ( scenery scrape, dropped stageweight or screw caught in a Mole or Heron cable guard ) . Also, wasn’t the lino rather softer than the subsequent resin floor so that peds were quite hard to push around. Lulu the elephant, and the occasional horse could always be relied upon to provide an instant skating rink. I’m sure that Dudley will be along soon to tell us when the resin floors arrived, mid 70s I think.

Dudley Darby

There was about half an inch of play in the Mole suspension, unlike the Heron which had none. The Mole was used to test the floors originally in TVC. You could feel the change in vibration over variations of about 1mm. Later a Heron was used as it was far more rigid, and relied heavily on floors being flat.

Initially the floors were actually quarter-inch lino on an asphalt base straight onto the floor slab in TVC. Some of the Lime Grove ones were onto the original wooded block floor. The asphalt acted as a shock absorber and was easier to level than concrete in those days as concrete shrunk unevenly as it dried out. I’ve still got a piece from TC1, amazing stuff. As the lino had to be replaced and the original stock ran out, 3/8” lino was used as a replacement, made especially in Norway (except for one disastrous batch made in Holland which went soft – that was used in TC5). The first polyester resin floor was laid in Elstree A, but the Chief Engineer of the time had decreed that all studio floors would have lino, so it was covered in lino in spite of various protestations. That was in 1989. Elstree D was I think the first to have a full resin floor without any concrete. Static was a problem with the early ones, the resin was a good insulator. Later, freeflow epoxy replaced the polyester, getting rid of the need for styrene as the catalyst when laying it. Static was always worse on cold winter days where the humidity was low. It also wasn’t helped when the humidifiers were taken out of the ventilation system after a Legionella scare. Antistatic treatments were developed which helped a lot. Now, antistatic properties are built in either using carbon fibres (reasonably successful) or graphite (consistently better). One company laid all of the main studio floors in TVC (not News) and Elstree from 1961 until it closed. BH used a different contractor, as did Media City.

Geoff Fletcher

In R2 with a Heron, the dip could cause total lack of traction as the dolly drove on diagonal wheels so if one was over the dip it wouldn’t go anywhere. I really liked tracking the Heron. Some were not good as others – they would gradually drift out of square as the day wore on – you got to know the bad ones by their number (on the back) and rejected them if you had a three day play to cope with. On Crew 14, if Dave Mutton was on the front and had his seat at right angles, we had to have an outrider standing on the opposite corner at the front as Dave was a big lad (to put it mildly) and his weight would lift the opposite wheel off the deck on fast moves.

Peter Fox

And the Mole would make dents in new lino overnight

It wasn’t so much how hard peds were to push on lino, we knew no better. That’s not quite true because a monochrome turret camera seemed quite agile, but it was amazing when the resin came along and peds would fly with the tiniest of pushes, not to mention having lighter 3 tube Link cameras on Fulmars, rather than a quarter ton of EMI plus Hydraulic Ped. (Well, maybe not actually five hundred weight, but well on the way to it.)

Steve Edwards

An EMI 2001 camera + Pan and Tilt head + HP pedestal inc weights = 695 lbs (approx) so you might say that you’re nearly at 1/3rd of a ton!

The Mole Richardson MPRC crane didn’t have any suspension, as it didn’t have any springs.

I had once heard that the diff was from an early Ford. The motor is a worm drive and the axle layout very much resembles that used on Fork lift trucks. The wheels themselves are of solid fork lift type as are the drive flanges from the half shafts ….

However, the rear steering axle does resemble a cast beam axle found on earlier cars (before the days of Independent suspension) but obviously with this being in the order of approx 3 ft wide had either been:

1: A completely new design but similar casting to that found on a car or,

2: A copy of a car beam axle cast to a narrower track/width.

On the other hand it may just simply be one taken from a fork lift or similar.

Peter Fox

Bill Marshall was our Head of Mechanical Workshop: we looked at one that was dismantled, and spread all over the floor during a systematic refurbishment of the six that we had at the time.

Amongst other things Bill had new half shafts fabricated at great expense and we never broke another one after that! The old ones were meant to break and had a weak weld at the wheel end. That way it was easy to pull out the broken one from the outside rather than dismantle the axle. The change in philosophy was to make them of really modern steel. I think they were all pissed off with us LE types breaking them so regularly. It was mutual.

Bill commented that he could never get any more diffs but they were in pristine condition and it was self evidently true. That’s when I thought springs were in evidence, really stiff and short but you would surely need a little bit of compliance in the system or there would always be one wheel trying to lift off the ground, the casting wasn’t going bend much!

Peter Booth

These conversations remind me off many happy moments – especially steering the three-man Mole on a drama in Bristol – with Teddy Williams shouting from the front – within two months of leaving school. What had I got into?

Geoff Fletcher

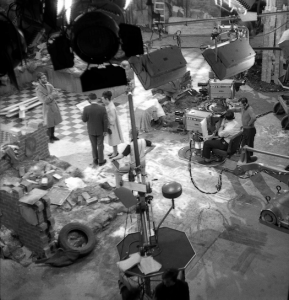

Just a reminder of Moles on dramas – Crew 4 – my first crew on joining BBC Tech Ops in October 1963. This was taken on 22 March 1964 shortly before I was posted to Evesham for TO19. Reg Poulter on the Mole, Pete Ware on the ped, “Ted’s Cathedral” was the play, TC4 the studio.