The art of Roger Bunce

John Henshall

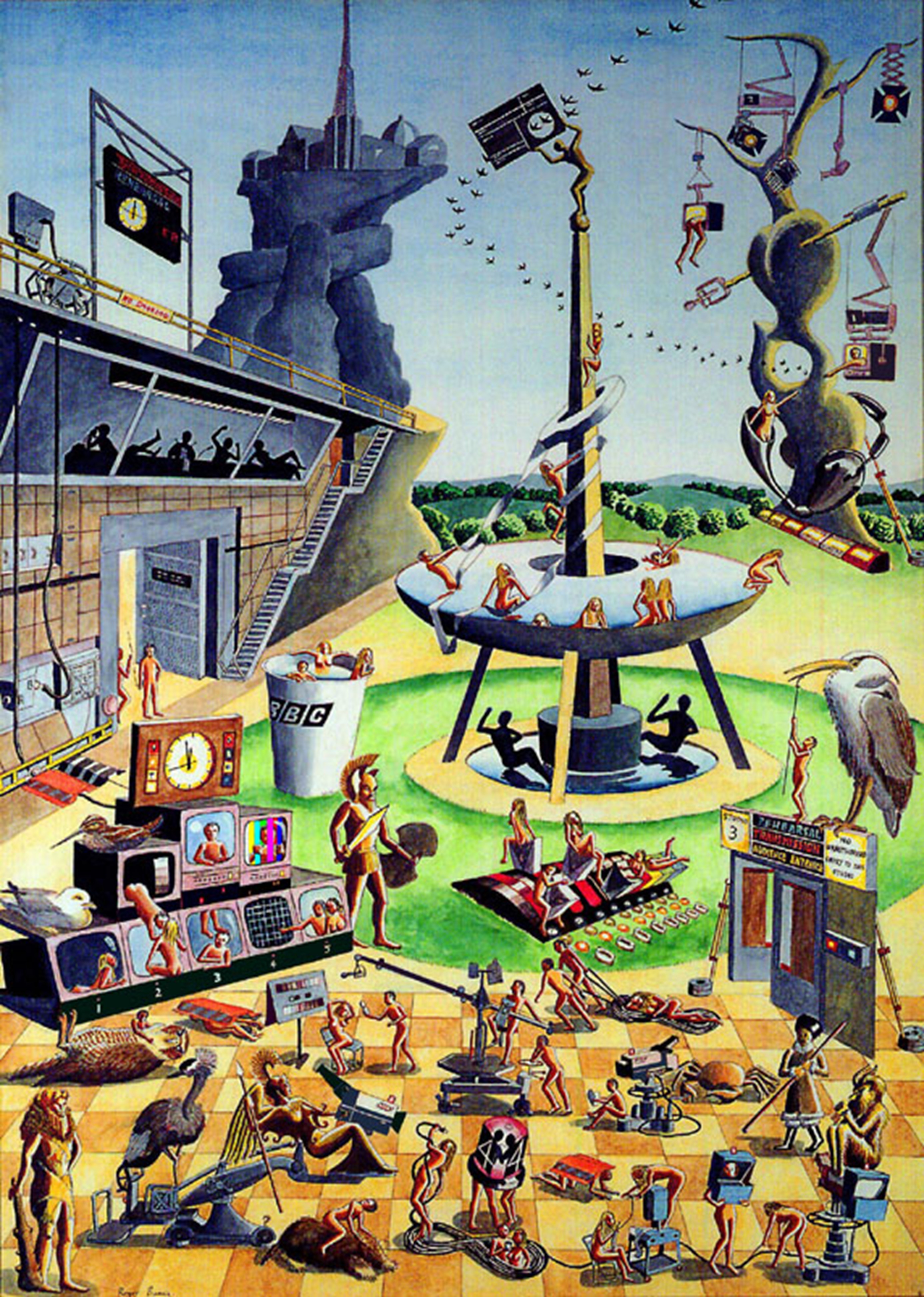

Roger Bunce was a fellow cameraman on Crew 14. He is also a talented artist and writer of satirical comedy. Had he become a programme maker, his shows would undoubtedly have broken many moulds. Amongst other artistic gems, Roger drew some excellent cartoons for the Guild of Television Cameramen’s early magazine.

Roger was fascinated by the weird and wonderful work of the Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), a surrealist long before the term was invented. He particularly liked his dreamlike Garden of Eden triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights.

One day Roger showed me his preliminary sketches of how he thought Bosch would have portrayed the Television Centre. I was thinking about leaving the BBC and wanted something to remind me of the idiosyncrasies of the place I had loved working.

Roger Bunce

It is unlikely that the project would have progressed very far, except that John Henshall took an interest in my preliminary sketches, and offered to buy the finished painting. Thus developed “The Studio of Earthly Delights” by ‘Hierogermus’ Bunce: a ‘Renaissance masterpiece’ in ball-point pen, kiddies’ water colours, blue-black ink, felt tips, snowpake – and anything else I had to hand.

For those who were there, in the Golden Age of Television, most of the symbolism may be self-evident, even if you weren’t abusing the fashionable substances of the time. But, for those who would like a guided tour…

In the distance, on an impossible rocky crag, stands Alexandra Palace – Television’s own Garden of Eden. The bizarrely misshapen tree on the right is a typical piece of Bosch design, but has been festooned with lamps and slung picture monitors. It is encircled by a gigantic headset, and is transfixed by a fishing rod. The statue of Helios (from the central courtyard of Television Centre) holds, not his hollow sun-disc, but a hollow Ampex videotape clock, while a huge reel of camera tape twines around his column.

The population of naked people, including slender ladies with long, crinkly, blonde hair, are taken from Bosch. Most of their activities are copied directly from his triptych, but have been given a televisual twist. The couple doing something strange under a fire board are based on a couple doing something similar under a mussel shell. The figures under a huge camera cue-light are based on a similar group under a large translucent flower head. The naked lady doing an erotic dance with a camera cable is based on – er – actually she’s probably just a fantasy of my own.

Others are engaged in typical studio activities: rigging, operating, reading a book while sitting on a camera pedestal base, or taking a clandestine smoke in the entrance to the technical store room, under the ‘No Smoking’ sign. (No one’s sitting on the yellow rail. How could I have missed that?) The figures in the gallery are all behaving stereotypically. The Technical Manager II is answering the phone (isn’t that all they ever did?), the Vision Mixer is knitting (certain of the more mature, female Vision Mixers were noted for their ability to knit and mix simultaneously – knit one, pearl one, cut one), the Director is ranting and waving his arms (as some do), while the Producer’s Assistant provides a touch of glamour.

The Boschian menagerie of birds, beasts and mythological characters are all visual puns, based on camera terminology – for example Pan, Crab and Crane. Most of the birds bear the names of Vinten camera mountings – Heron, Fulmar, Snipe, and the deceased Peregrine, one of their less successful ventures. The East-European figure, with fur hat and pointy stick, is Vlad the Impaler, representing the VLAD – the acronym for the Vinten Low-Angle Dolly. The characters from Greek mythology bear the names of Chapman camera cranes – Nike, Titan and Hercules. And, of course, there’s Mole-Richardson’s Motion Picture Research Council’s camera crane, known to everyone as the Mole.

Many of the details are now historical period pieces – the EMI 2001 cameras, the Vinten HP camera pedestal, the black plastic ST&C headset, the BBC designed vision mixing panel with its quadrant faders, the old zebra-striped wooden fire-board beside the newfangled orange fibre-glass one, the standard BBC issue paper cup (ideal for drinking VT Tea) and the blackboard-and-chalk Ampex videotape clock.

The blue Autocue prompting equipment of the time used an electro-mechanical system. Previously, there had been a purely mechanical system, using giant typewriters and carbon paper to create two identical copies of the script on large rolls of sprocketed paper. Later, it was all done by computer. In the 1970s the script was typed onto a narrow roll of paper. This was scrolled beneath a camera on the operator’s console and the output was fed to a monitor below the camera lens, reflected to appear as though in front of the lens by a mirror at an angle of 45 degrees.

In front of the line-up chart poses the Studio Line-Up Girl (a title which created the unfortunate acronym SLUG). In the early days of colour TV great efforts were made to achieve realistic flesh tones. Other colours could afford to be slightly inaccurate, but if the faces looked unnatural then the whole picture would be unconvincing. Experiments were made with layers of translucent, pink plastic, attempting to create something that had the colour, texture and reflectivity of human flesh. Some of them were revoltingly realistic. But nothing was ever as effective as lining up the cameras on a real human face. That face was usually provided by an attractive young lady, much to the delight of the all-male studio engineering department, who finally had someone female to talk to and point their light meters at. The Studio Line-Up Girl was later replaced by a high-quality photograph.

In the gantry may be seen a Cable Hoist. These were the days when camera cables really were ‘as thick as a man’s arm’, and very heavy. There was official concern about the welfare of cameramen as they dragged them in and out of technical stores. One solution was to coil them on a drum in the gantry, and use an electric winch to raise and lower them. These hoists may have been falling into disuse by this time since, on the other side of the painting, a pair of figures may be seen manually dragging out an eight of cable – and another naked lady.

John Henshall

I paid Roger £15 for the painting, which initially hung in my office in Richmond, Surrey, and then in our offices in Brentford. This is a real work of art in the best allegorical tradition, symbolising much of that which made up daily life at the creative edge in Television Centre. I would go so far as to say that it reflects the eye of a genius.

The original colours have faded, as is the way with water colours. With hindsight, I should have positioned this gem in dim light, for I think Roger painted it using ephemeral media, knowing that the colours would slowly fade to white at the same time as Television Centre slowly faded to black. Nothing lives forever.”