[Ed: in the first lockdown, Bernie suggested that we offer pictures of our walks. This one provoked some discussion!]

Alec Bray

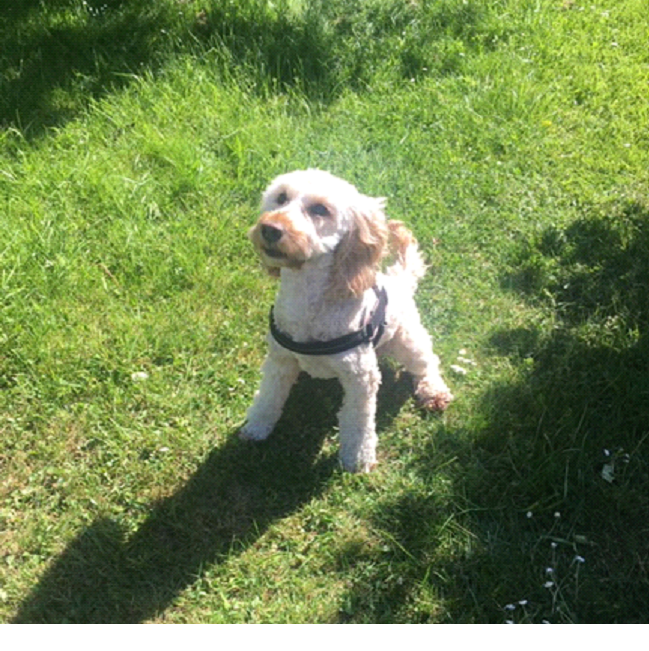

Some 8 miles away from our home is Watership Down. It is a real place!A bridle path called the Wayfarers’ Walk runs along the ridge of the Down. So today (17 June 2020), Chester went on his walk to Watership Down.

This is a view of the top of Watership Down from the pathway.

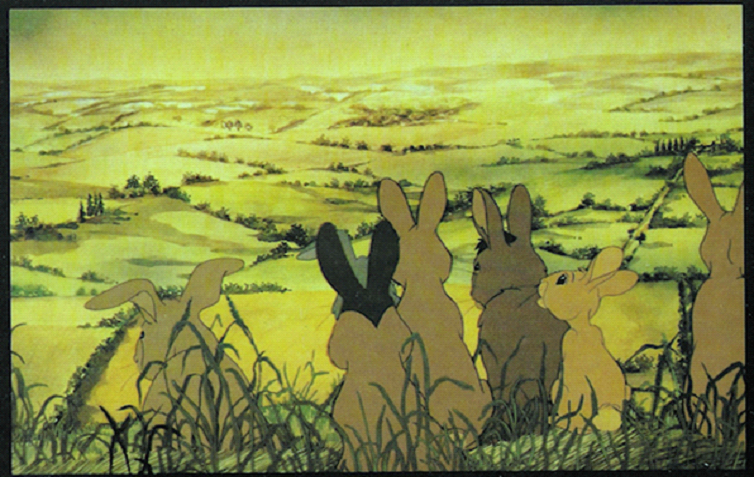

Here is a still from the 1978 movie:

The film’s title song was “Bright Eyes” (why do you turn so pale? no phantom power?) The film “Watership Down” was first released to the UK on 19 October 1978.

It was very muggy on top of the ridge today, and Chester was feeling the heat – look at that long tongue hanging out! We walked back slowly, keeping in the shade.

Some people like to navigate by Pubs, others by Churches. For those of you who like to navigate by transmitters, Watership Down is along a track on the opposite side of the Kingsclere-Overton road to the Hannington transmitter.

Geoff Hawkes

I particularly liked the picture second from bottom where you have included lots of sky with clouds. It’s not easy to decide how much sky to include and where to put the horizon line. I usually think in thirds rather than a fifty-fifty split but yours works well. Skies are important and Constable is said to have painted one every day.I hope Chester is enjoying lots of sniffs on your country walks. I’ve not taken my daughter’s dog, Summer out since lockdown but she’s been bringing her here so she can have a run in our orchard and I can see her.

Roger Bunce

Geoff says “It’s not easy to decide how much sky to include and where to put the horizon line.”On the Golden Section, Geoff! Usually on the Golden Section. (0.618034 or 0.381966) They must have covered that when filling in your Ration Book? (I know, it’s a long time ago now!)

John Nottage

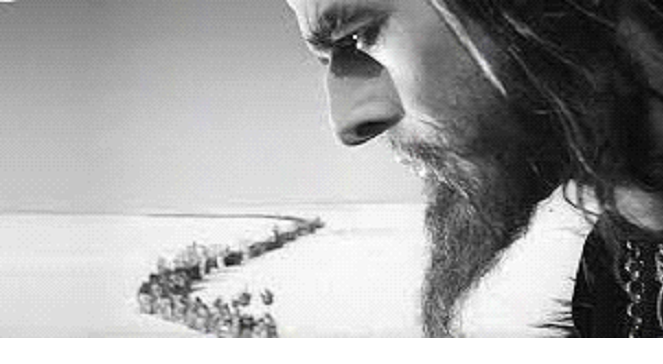

Try telling that to Sergei Eisenstein…Roger Bunce

Virtually perfect. I don’t think he needs to be told. He probably invented it!

Geoff Hawkes

…what would Eisenstein have said to Roger, [please] enlighten us…John Nottage

I imagined you would have seen “Alexander Nevsky”?YouTube: Alexander Nevsky

From about 57 minutes in there are some good examples.

5% land 95% sky – fantastic shots!

Geoff Hawkes

A choice of viewing for you on the subject of where to put the horizon line in photos of land (or sea) and sky. Lower third, upper third or straight down the middle?The poppies looked great as did the sky, so which deserved a larger share of the frame? How to satisfy Roger’s rule about observing the Golden Section and Mr Nevsky and his followers at the same time?

If anyone is inclined to see them and take an offering of their own, the poppies are about a mile from Chesham town centre. OS Explorer 181, Ref SP 942 023. It’s a pleasant walk across the fields with plenty of space to keep away from other people. You can drive but it’s a single track road and parking is limited.

Roger Bunce

Great pictures Geoff.My preference is for the first one, because the clouds form a naturally elliptical composition which keeps the eye within the frame. The poppies are very pretty, but they haven’t bothered to form a composition. Clever clouds. Silly flowers.

The thing about rules, Geoff, as we all know, is that they are there to be broken – preferably smashed to smithereens. But the trick is to break them deliberately, for artistic effect, rather than breaking them accidentally, because you didn’t know they were there. The one rule you mustn’t break is – Always put things where you, personally, think they look nicest! (Unless the Director wants something different, in which case you obey orders on the initial blocking but, during subsequent rehearsals, sneak it back towards what you wanted in the first place! Probably a good job that I’ve retired.)

Horizon Lines – The problem with any straight line passing through a rectangular frame is that, if its too close to the middle, it’ll chop your image into two separate pictures. This, I would suggest, is the problem with your Shot Three: a nice picture of poppies and a nice picture of clouds (although not as nice as shot one) but nothing holding the two halves together. It could almost be a split-screen.

Traditional way of avoiding this problem:

- 1: Exclude the horizon-line from frame.

- 2: Place the horizon-line very close to the top or bottom of frame – it then ceases to be a dividing line, and becomes a border, helping to keep the eye within the frame.

- 3: Place the horizon-line on the Golden Section. This is where the ratio between the smaller bit and the larger bit is equal to the ratio between the larger bit and the whole frame.

In a way that makes a sort of intuitive sense, but I am unable to explain logically, this is supposed to merge the two disparate elements into a single coherent composition.

Obviously, no cameraman puts a ruler across his viewfinder to measure the Golden Section. You just put the horizon-line where it looks nicest. But if you were to measure your picture, after the event, you’d probably be surprised how close you were. It does seem to work. And it’s an amazingly effective way of concealing a split-screen!

Art Historians will tell you that this was discovered by the Greeks, who built their temples following this proportion. Like most things said by Art Historians, it is likely to be complete rubbish! In my misspent youth, I measured pictures of Greek temples, and failed to find any confirmation.

But, if you like mathematical puzzles, the Golden Section ratio is a delightful number to play games with. Usually represented by the Greek letter phi (φ), it is approximately equal to 2/3, closer to 3/5, even closer to 5/8, yet closer to 8/13, closer still to 13/21, etc. No, I haven’t remembered these numbers, I’m making them up as I go along. Each new number is the sum of the previous two numbers. This is known as Fibonacci’s Series, an apparently completely pointless string of numbers, whose ratios grow ever closer to the Golden Section Ratio.

It’s the only number I know which can be raised to powers of itself, simply by addition or subtraction. E.g. 1 – φ = φ squared, 1+ φ = 1/ φ.

If you start Fibonacci’s Series with 1 and φ , all subsequently terms will be increasing negative powers of φ.

Play with this number long enough and you’ll go mad, and start measuring pictures of Greek temples.

Tony Grant

When talking framing and composition, using your viewfinder, I have always passed on what I was told early on in my career: ‘There is only one rule for pictorial framing/composition – ‘if it looks right, it is right.’ I could bore you all to pieces by how I use to delve into the difference between framing and composition when running workshops, trying courses, etc. but you’ve heard it all before!

Roger Bunce

Of course, as definition increases, it will be possible to blow the image up to cover a whole wall. The picture will fill your field of view. Then the whole concept of a "Frame" will no longer apply, and with it will go all our concepts of framing and composition. A range of new "rules" will have to be invented.Except for those who still want to watch things on their phones.

John Vincent

Rod Taylor’s advice?“Go to the National Gallery.”