Bernie Newnham

I just want to point out that what we are recording, like everything on websites, is terribly fragile. Currently it’s all well backed up by the hosting provider and me, but it’s just magnetic stuff on a disc drive. … poof! – all gone.Graeme Wall

Would the British Library be interested? They have a project to preserve digital records of interest.Mike Jordan

It isn’t just memories and thousands of photos, but all the Wood Norton etc training information (back to first course) OB planning sheets, souvenir booklets, programme videos and BBC things and books. The loft [is] FULL of quite legal bits and pieces of test equipment saved from skips, special home-made adaptor boxes/leads which I doubt anyone would want and I haven’t even started on my bits to plumb/electrify/hify/satbits the house etc etc.Is it just us BBC blokes who have a hoarder/collector disease?

Where would it all go (and by whom) if anything happened and a little flat was calling?

Chris Woolf

The point to recognise is that, while many individual items may be of little historical worth, these artefacts add up to a record of a craft that has had a significant effect on our culture for ~70 years. It is a craft that is dying out because productions simply aren’t made in the same fashion now, and won’t be again in the future. Television will still exist but not the version that was forged from the 1950s till the 1980s or 1990s. Once automation, reduced crewing, self-shooting etc took over the old craft faded, and though there are remnants still functioning (and merging with established film techniques) they are at best obsolescent.There are close parallels with some of the skills that arose during the early part of the industrial revolution, and disappeared by the end of it because the crafts were superseded by different techniques.

As an instance, early traction engines were built on an individual basis by groups of craftsmen: later on factory building and standardisation of common parts changed all this, in much the same way that robot welding has taken over from craftspeople in car-making and other industries.

There’s no point in weeping over such changes, but there is a powerful argument for documenting a craft before it becomes forgotten, and describing many of its details that would be hard to rediscover once everyone concerned is pushing Vinten peds and waving Fisher booms in the hereafter.

Alan Taylor

There is usually documentation and photographs for equipment, but the way it was used in the real world is rarely documented.Some of you will have been told about the grandfather of my ex-wife. He was an engine driver on GWR in the final years of steam and often used to talk about “Caerphilly Castle” as though it was his personal loco.

We discovered that it was a static exhibition in a museum and took him to see it. He was very moved to see it in pristine condition and one of the museum staff allowed him to go onto the footplate. It was obvious that he knew the what even the most minor controls did.

A more senior member of staff was called and at one point asked if he knew what two tapped holes in the surround for the driver’s window were for because they aren’t seen in similar locomotives. He immediately explained that they were for the display of a dynamometer while they were doing efficiency trials in the 1950s.

This impressed the staff as it had puzzled them for years, but made perfect sense and even fitted in with some of the paperwork. We were then invited upstairs to see photos of that loco in operation and it was quite obviously him driving it in many of those pictures. They asked him all sorts of stuff about driving it because although they knew what all the controls did, in many cases they didn’t know why or how they were used. He talked at great length about how you operate the loco differently in cold weather, how you temporarily boost the power when approaching gradients, how to read the track to keep things running smoothly, how certain long left hand bends cause problems at high speed while similar right hand bends don’t, what you do when starting up and shutting down, but most of all he explained that you don’t go by the dials, but how it feels and sounds.

The museum were thrilled to get such a comprehensive description of how the loco was operated and much of it was new to them. Granddad just shrugged it all of and couldn’t imagine how “so called experts” didn’t already know such trivial matters.

For my part I’ve previously explained on here how traumatic my first Sypher dub was in Sypher 1. I had been shown how it worked, had done a practice session, followed the cockpit drill and knew that type of sound desk well, but on the day I really struggled, especially on the first day. Fortunately the director, Jon Amiel, was very supportive and insisted that we can get the dub done. After it was over, I had a long discussion with Ian Leiper who patiently explained how you manage a dubbing session, how to keep track of your progress and how to deliver consistent results. That sort of thing is rarely explained in training manuals, but is probably more important than knowing what the knobs do.

The bottom line is that those who do a job well usually take into account any number of factors which are not at all obvious. To an experienced operator, what they do is so natural and intuitive that it scarcely needs mentioning. Preserving those memories and techniques is something which can only be done while those people are still around. Once the people have passed on, that wealth of information vanishes unless it has been recorded in some way.

Geoff Hawkes

Great story about Alan’s “grandfather” and thanks for sharing it. The conversation he had with the Museum staff should’ve been recorded for the sound archive and an edited version put with the exhibit at the museum for visitors to listen to, as it would make the history come alive.Pat Heigham

Alan Taylor’s ‘Granddad’s reminiscences should have been recorded.Which year did this take place – maybe video handycams weren’t around? I should have loved to have shot on that.

Alan Taylor

The occasion when my ex-wife’s grandfather visited his old loco must have been in the mid 1970s as he died in 1979. The way that visit turned out was entirely unexpected. We merely intended to show him his old engine, but things just sort of took off. The museum staff did take notes and they later sent him a lovely print of one of their pictures with him on the footplate.Brian Summers

Mike is not the only one with a VAST amount of stuff. I am a hoarder first class!There is the camera and studio equipment collection (best measured in Tonnes), a ‘scope collection, Marconi Instruments collection, Test meter collection, several amateur radio RX/TX.

Then there is the technical Library, some 4000 odd books/manuals/documents/tec instructions…….. and of course the OB van MCR21 which now belongs to the Broadcast Television Technology Trust.

The Trust is currently working on MCR21 and we hope to have it out on public display next year probably at the Amberley Chalk Pits Museum, but there is much to do. We have the support of the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) in funding some 90% of the MCR21 project and we are working to raise the remaining 10% and then there is the long term funding to find.

The Trust has great plans for the future, time and money permitting, we would love to set up a “Proper Museum” to display as save for the future the technology that we have used to make television and radio programmes that the world appreciates.

We do hope that with the support and help of others that we will be able to save, show, inspire, future generations of engineers and producers the history of Television and Radio.

Hugh Sheppard

So good to hear of all this, but perhaps in due course you might tell me of the likely type of ‘scanner’ that I first visited in 1958 at the While City “Horse of the Year Show”, Peter Dimmock as producer. I ask because it may help a contribution to memories of Peter. I stood behind the producer and EM lengthways on in the van for a 3-camera broadcast as I remember it. Maybe sound was between the mixing desk etc, and the monitors, but I can’t be sure.Brian Summers

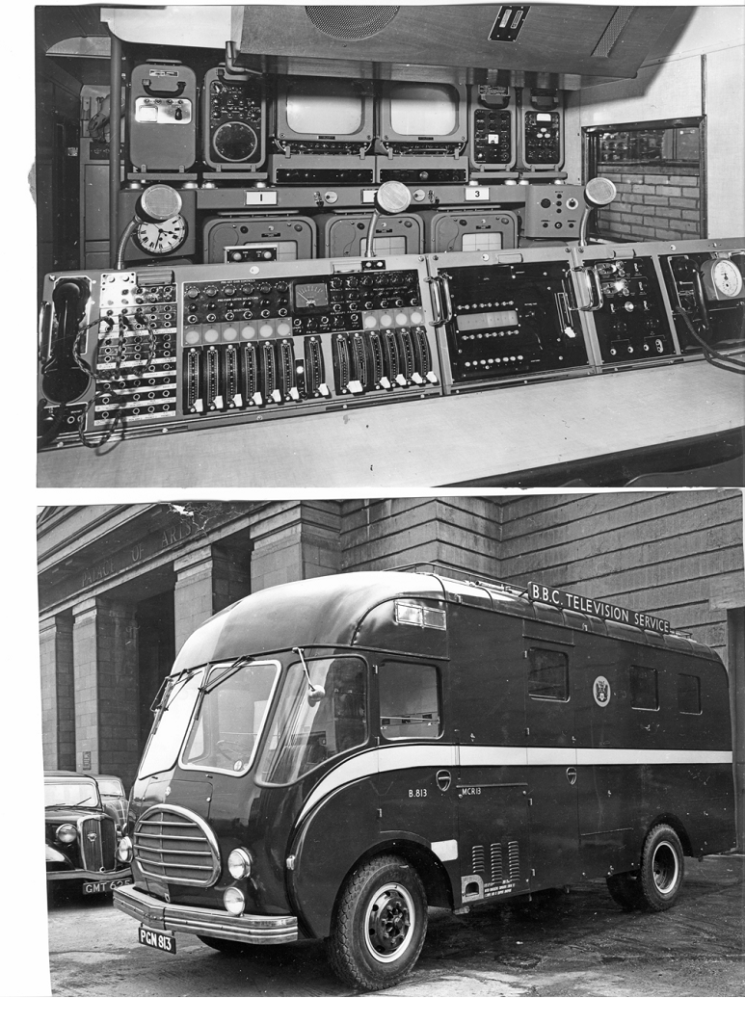

Its difficult to know exactly “which” scanner did a particular programme but it would, for a high profile programme like the “Horse of the Year”, likely be one of the newer ones in the MCR13 to MCR16 series. Fitted with three Marconi Mk III cameras and introduced in 1954/5 4 scanners with consecutive registration numbers PGN813 – PGN816The earlier scanners MCR4 to MCR 10 were semi-trailers and by 1958 would have been shipped off to the regions.

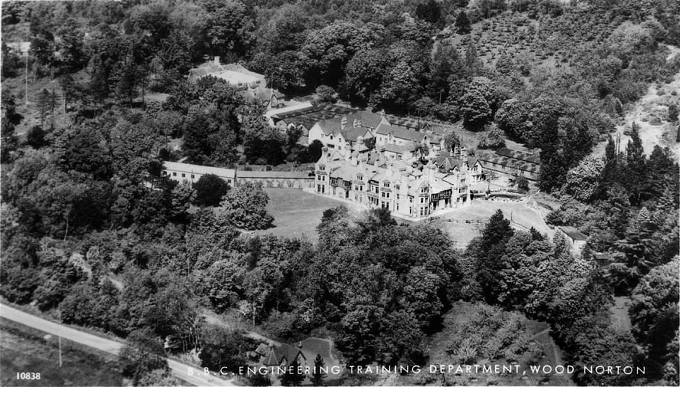

Picture of MCR13 outside the palace of arts below.

Robert Miles

Interesting to see in the top picture of the interior of the MCR with the quadrant faders all in the down position. I can’t really make out the graticule markings and wondered whether on this near vertical sound desk you would have faded up the channel from the position shown? If this was the case then when did BBC TV adopt the fading up of a channel from the top position? Did radio follow the same path?Alan Taylor

I’m pretty sure that all the faders in that picture are fully faded up to 100% gain. If you think about operating them when they’re about 75% gain during a programme, having the fader near the bottom while you’re using it is fairly comfortable because your wrist can rest on the desk. The opposite way round would be rather uncomfortable. I apply the same logic to quadrant faders when mounted horizontally. Reaching over the fader for normal operation would be uncomfortable. That is the logic I use to explain why certain organisations fade the BBC way while most don’t. Longer established studios evolved via quadrant faders.Nick Ware

I wondered about that too [quadrant faders all in the down position], and even wondered if there were quadrant faders that long ago. How simple things were then! But looking at it on iPad I can stretch the picture enough to see that the semi-logarithmic (tapered law) markings get closer at the bottom end, presumably the ‘infinity’ symbol at the bottom, and wider apart at the top end where finer control is needed, reducing to single digit at the top. So, I think they were non Beeb practice, fading up, not down.It struck me as odd from day one, when I first saw TC sound and vision mixers, that vision faders faded up, which was entirely logical, while sound faded ‘down’ for ‘up’.

Dave Mundy

Hence Norman Greaves’s elastic band for a quick fade out!Pat Heigham

Yes, Norman used to fasten a rubber band to the knob of the audience group fader, attach the other end to a fixed point on the desk, (the handle of the channel module), then after fading up for the laugh/reaction, would just let it go to gradually fade out, leaving his hands free to concentrate on the other mic faders!The story fed to me (I suspect it was rather ‘tongue-in-cheek’) was that if the Sound Supervisor should suffer a collapse during transmission, and slumped forward over the desk with his hands on the faders, the body movement would tend to push the faders closed, avoiding a massive overmod and taking the transmitter off the air. Anyone else hear this story?

Maybe there is a psychological idea, though: needing to make the sound louder, one pulls it towards you, while wanting to make it quieter, push it away. But then the BBC always had its own logic. My father (who was military) used to say: “There are three ways of doing something – the Right Way, the Wrong Way and the Army Way”. Substitute ‘BBC’ for ‘Army’!

Norman was a hugely steadying presence when under his training, I was mixing “Blue Peter”, live. That show, one would think quite simple, could actually turn out to be rather hairy!

Pat Heigham

A good few years ago, I was scheduled to work on the ‘final’ performance of “Beyond the Fringe” from the TV Theatre. I managed to make a ¼” audio recording of it for my library, but longed for a picture version.Recently discovered a DVD available, probably taken off a VHS, as the quality is not great, but great to have it as one remembered.

It is said that a deal of the material would not be acceptable these days, but I think it was very witty, barbed and clever.

Sad to realise that of the original four, only Alan Bennett is still around.

And finally …

A Postcard of the BBC Engineering Training Department at Wood Norton