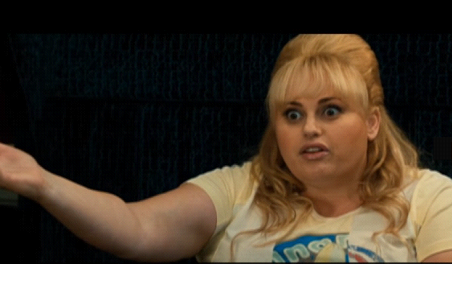

Film “The Hustle”

Bernie Newnham

I was hunting Netflix …, looking for something watchable – which isn’t always that easy – and found a film called “The Hustle”. Having been a fan of BBC “Hustle”, I started to watch. It’s not cheap stuff, starring Anne Hathaway and Rebel Wilson, but it did rather turn out to be rubbish, and I gave up.Before I left I watched this scene in a railway carriage. Please ignore the cut down picture quality and slight misframing… . Just watch the cutting –

Chris Woolf

Maybe the director thinks everyone has a squint and doesn’t actually look at each when they talk….

Pat Heigham

Talk about ‘crossing the line’ ( not referring to the railway variety, here!)

Have either the director or cameraman ever been to a decent film school?

It used to be important to establish the geography of a set.

A usual cameraman I worked with, related a story:

The director of the job he got one day wanted a handheld tracking shot, backwards down a street and said: “can you shoot the close -ups at the same time?” And “ I want it all to look cosmic”.

What was he on?

Graeme Wall

Been there, been baffled many a time!

Vernon Dyer

OMG! Mind you, taking the wide from the opposite side of the line to the singles seems to be the way to do it these days – take a look at “Coronation Street”. I keep forgetting to check the name of the director of the episode, and I’ve realised why his/her credit is at the beginning!

Crossing the line several times in the same scene has sadly become the norm.

Sometimes I miss work, and sometimes I look at what goes on these days and think I’m well out of it!

Rant over, I feel better now!

Bernie Newnham

Not only crossing the line, Anne Hathaway’s eyeline is always for when Rebel Wilson’s position is on the downstage end of the seat.

One thing about working in TC1 or wherever, we just couldn’t do those shots, even if we’d wanted to, which we didn’t.

Shetland

John Barlow

For those of us that thought the framing on “Shetland” was pretentious and/or ugly I present the Director’s rationale.

Lee Haven Jones, Director of “Shetland”, writes:

“…The directorial challenge with every piece of drama is to define the imagery that gives the work its identity; which elevates it from being mere verisimilitude to something more expressive. In addition to the aesthetic weight offered by locations – the natural or built environment, and the elements – I endeavour to create visual leitmotifs and tonal elements that recur throughout a piece of work that augment the world the characters, and therefore the viewers, inhabit. In this regard, directing is not just about capturing and conveying narrative – it is also concerned with conjuring an ambiance, creating a world and setting a tone. It is about making an audience ‘feel’.

The framing in this current series of “Shetland” is influenced by, and suggestive of, two elements:

First, my initial impression of the Shetland Islands. A subarctic archipelago sitting somewhere between sea and sky, it is a barren, expansive, otherworldly landscape with very few vertical elements (trees, mountains, high-rise buildings), and vast, seemingly endless horizons. Hence the acres of headroom.

Secondly, it is designed to augment the atmosphere of David Kane’s script and make the characters appear uncomfortable in their environment; it is, in many ways, a nod to the genre of the piece. It is intended as a visual device to represent and reflect the uneasiness of the individuals involved in the drama and to heighten tension. It is an attempt to place the audience at the beating heart of the story; it aims to give the viewer an intravenous injection of mood as well as an engaging ‘edge-of-your-seat’ story… “

David Denness

Pretentious claptrap.

Alasdair Lawrance

Utter tosh! Where do these people get it? The mere fact he has to explain it shows it has failed.

Nick Ware

In this household we have two choices, the on button, or the off button. We voted with the off button.

Roger Bunce

Maybe we should stop calling our conventions “Rules”, because that just encourages people to break them. If we call them “Tricks of the Trade”, which is what they really are, people will feel thick for not knowing them.

Dave Wagner

Good call, Roger.

Tricks of the trade they are, and not just for cameras. We had a few in sound but not many realised or understood them!

John Barlow

I’ve been asked to give a talk about making programmes and I wonder if others on the Tech Ops site might help me to answer a question that is frequently put and to which I have difficulty providing positive answers: The framing of some shots!

We try to explain to students that there is a universal grammar of Film/TV production that, albeit far from rigid, tends to follow accepted rules to help the viewer understand and enjoy the content. Of course, there will, thank heavens, always be situations when rules need to be broken; but in these cases, there needs to be a rationale. Reverse angles from referees’ body worn cameras might disorientate but, on balance further explain the content. “Looking Room” can be negative if the character is reacting /

listening to another speaking from behind them etc. Good examples of when to break “rules”.

I intend to use “Shetland” to illustrate my difficulties, but can easily find numerous other examples such as “Luther”. Silverprint (the Production company) extols that it is “…driven by the talent of the writers and directors we work with and are passionate about enabling and producing their vision to create distinctive and ambitious drama…”

Elsewhere that Silverprint feels it is “… important that our label had its own distinctive identity…” Now these are virtues that are excellent but how is distinctive to be achieved?

I am including some screen shots that will feature, as high-quality versions, in future talks and would really like to include positive or negative comments on the reasons or logic of this type of framing and how this adds to the viewers experience.

My feeling, and please rubbish this, is that Production companies want their product to be somehow different and the following examples serve only to make this possible. If I’m right, then storytelling has been forfeited to the expedient of a jarring style for no gain in production values. Freelance staff understand in this competitive environment that whatever a Director calls for is best delivered as future employment depends on working relationships. Perhaps only those no longer reliant on the next job, like me, can speak out freely?

The… lectures will feature decent images with all copyright clearances, I believe are typical. As you see the distinctive style seems to be to intersperse “normal framing” with deliberately mis-framed shots, but why?

Barry Bonner

Definitely pretentious. Lee’s missive deserves an outing in “Private Eye”’s Pseuds Corner!

Geoff Fletcher

Trying to be objective in the face of the onslaught of media speak bxxxshxt!

In my view, they expressed the feel of the landscape better in the Wollander series – without the weird framing.

Vernon Dyer

Most definitely! It reminds me of the late great Pete Hills, who listened to something like this, then looked at his Mole tracker and – after a pause for effect – said: “I think he wants us to track in, Squire!”

Roger Bunce

I too have been wincing my way through “Shetland” – although I quite enjoy the plots.

I always told my students that there are Rules, but there is no Rule that says you can’t break the Rules. The important things is that you know what the Rules are; why they are there; what effect they are intended to achieve, and that you break them deliberately, knowing the different effect that will result.

If “Shetland” broke the rules consistently, then I might imagine that the Director was trying to create a distinctive (if ugly) style. But it doesn’t: e.g. I’ve seen the headroom on the same character yo-yo up and down between consecutive shots. Why? Are you really trying to create a different effect on each cut?

I can only think that the rule-breaking on “Shetland” is a result of ignorance, and the Director (plus N thousand Producers, Associate Producers, Executive Producers, etc.) used to be very helpful Runners, but never really learned anything about television.

Your point about freelance Cameramen having to be obedient, is true. Just occasionally I see a shot which would have been well framed, if they’d cut after the head-turn, not before. These days the Cameraman doesn’t know how his shot will be edited after it leaves him. A Director who promises that a shot will only be used after the head-turn is not to be trusted, particularly if, during the edit, he discovers that he has forgotten to take the reverse.

Just be grateful that wobbly-vision has gone out of fashion – for a while.

Hugh Sheppard

I wish that I could be as certain – about anything. After 10% of my life in studios and 40% elsewhere in Beeb, I was as wedded to Roger’s principles as anyone. Then as retirement took me in it’s grip, I got out of the kitchen a bit more. In art, I’ve appreciated that the masters of craft such as Picasso and Hockney had a solid foundation from which they later diverged, with a following that grew in appreciation. Others, such as Emin and Hirst drifted away so early that to me their oeuvre is broken, but clearly not for others. Somewhere along the line are the thousands of artists who try to be different and succeed, at least to a degree, and thousands more who try but who fail.

For me, “Shetland” succeeds in being different a fair bit of the time. The framing can be disconcerting I agree, but it gives an edginess that reflects the story. Would a classically-trained director have so readily stirred that into the imagery of an other-worldly part of Britain? I’m not at all sure; as it is I’ll buy into the attempt to be different, applauding the approach where it succeeds, while regretting that it is not more consistent.

But are we watching it? Generally ‘Yes’ it seems.

Albert Barber

I agree with Hugh as the two principles seem to encourage us to watch.

Tony Grant

Ah, rules. My dad always used to say that rules are for the guidance of wise men, and the observance by fools. Yes, if you know them, and why they’ve been formulated, then you can ‘break’ them if you wish to produce an effect, predictable or otherwise. Way back in those B&W days of two TV channels (BBC & ITV!) TV drama used to fade to black at the end of a scene, and then fade up on the next one. I think it was the drama “Say Nothing”, the precursor to ‘Z Cars’ that cut directly from one scene to the next. Shock, horror! The viewer will be totally lost! Wringing of hands and gnashing of teeth. But it’s now standard practice, in fact, does any programme fade to black and back up to the following scene during its running?

This thread started as a query on pictorial composition, so I haven’t mentioned sound, although there have been many comments on the forum about the necessity for intelligibility if one is to follow dialogue, in spite of the pictures getting in the way! The other aspect which has been briefly mentioned in passing is editing. Now, in multi-camera drama, vision mixing has little choice but to keep up with the performance. But in single camera production, the flow/timing is usually determined in the edit. In my short stint directing soap opera style drama, I used to run a scene in wide shot, with a VHS copy, and then run it through each time I set up a different shot. Thus there was a complete scene from each viewpoint to enable the flow to appear natural in the edit. The help and advice I received from the crews was invaluable in ensuring that I avoided any ‘holes’ in the shots due to being too close to the production, and not seeing the wood from the trees, or should that be vice versa? Continuity was a doddle with the VHS tape providing the answer to ‘Which hand did he pick up the glass with’[, or ‘when did he make that move’, ‘was the door already open’, etc. etc.

I had already learnt the hard way that a poor, inept edit can ruin even the best set of rushes. I had been working on a shoot for one of the Current Affairs strands about the development of the London Docklands. I could envisage a beautiful developing shot from a reflection in a puddle across the dock flagstones and settling on a beautifully framed shot of the docks with bollard foreground, framing the end shot. Due to wind and weather, it took me at least five attempts to produce the right combination of ripple in the opening reflection and the final framing. On viewing the transmitted piece, I was horrified to see one the earlier, failed attempts, which I’d aborted before the final framing, in the piece (with no sign of my masterpiece). Tracking down the director, I was told that they’d used that take “…Because it was the right length for the script….”

Journalists! Bollards!

Hugh Sheppard

“Say nothing”? Too many syllables methinks. My recollection of the forerunner of “Z Cars” was “Who me?” by Colin Morris, Producer/Director: Gil Calder and starring Lee Montague.(1959).

Chris Woolf

The viewing public don’t need to be taught the grammar, since the “rules” (rather than tricks of the trade) were formulated by the likes of Griffith and Eisenstein without that premise being necessary. They were making films for a visually uneducated public, and needed to present shots and scenes in a progression that gripped an audience’s attention, and told a story without confusion (unless you were John Ford and ~wanted~ to confuse during fight scenes).

The conventions weren’t drawn up by conservative rule-bound studio bosses, but by inventive directors in charge of every element of production, who worked out from first principles why line-crossing was usually unhelpful, why successions of shots “developed” a scene, how POV stuff could be incorporated etc. It all worked on the basis that an audience, who were entirely unskilled in visual arts, would understand intuitively what was being revealed to them. In exactly the same way the “trick” of cueing audio marginally before a cut makes people automatically pay attention to a new scene – no need to teach someone that that’s what it means. Audiences today are no more educated than they ever were.

All the conventions can be broken, but you need real talent to understand when that is possible, and it usually has to be done within a framework where the rules are being obeyed most of the time, so that the contrast means something.

Without that sort of knowledge, background and skill, the results are indeed just unpleasant and unfulfilling to watch, and the pseudo-explanations worthless.

Graeme Wall

Very well put.

Alasdair Lawrance

That’s a very valid point you make, Chris, but I still stand by my suggestion that you need some background to understand/interpret “Un Chien Andalou”, for example.

(Apologies if I sound like another candidate for Pseud’s Corner. If the film is strange, have a look here).

Albert Barber

This recent email from Chris sums it up very well, in that you have to:

1. Tell a story, and

2. Think of the audience.

If the audience don’t get it you have failed.

Rules are for the professionals, most of the audience wouldn’t know about crossing the line if you asked them. Eisenstein said in the Film sense (and I paraphrase here); “…Where two shots are joined it will produce an emotional effect in the storytelling for the audience…”

In the cases of us professionals, we know what this means and a challenge to the rules often causes debate. In the past history of film, challenges like the cut from an extreme wide to a BCU caused controversy. Now they do it all the time.

Very interesting, but on the edge of deja vu if you have been making films for a long time.

Dave Plowman

I used to work with a Producer/Director named Mike Dormer. I believe he also did some lecturing on the subject. Awfully nice bloke.

Police interview room scenes can be pretty long and boring visually – but [they are] often needed to tell the story.

At one point during the shooting of every which way, he’d say: “…Right. Now we can go where we want…”. I never had the courage to ask him to explain.

Mike Giles

For the first ethereal part of the director’s description of “Shetland” I agree… tosh, but when he gets to grips with describing what we see, I sympathise with his description and realise that I probably saw it his way without realising why. On the other hand, when I was looking out for jarring elements in the last episode, like others I didn’t see them, but that didn’t alter the mood for me, which is as much down to Douglas Henshall’s scarcely intelligible delivery as anything, not to mention the music – so I vote that sound wins.

Peter Fox

Something I did like was using a static, and square on very wide shot as a scene opener. Held for a minute or so (with close up sound), before conventionally crossing cutting, (across the line of the wide, but that’s fine) and also a very stylish square on wide, showing off the architecture if you like, of an interior action shot of the heroes “proceeding” somewhere. I thought: Using the set; Jonathan Miller, John Glennister, Rodney Taylor, Garth Tucker and… me. Others will occur to you? It needs a fair bit of extra effort from lighting and sound to make it work, so it doesn’t get overdone. Probably a very good thing, but nice to see now and again?

Roger Bunce

Yes, if it’s the one I’m thinking of, I did notice it. Big square-on wide shot against a bright window, then cut across the line to the closer shots (as they had to, unless they were going to shoot it all against the window light), but stayed on the right side of the line after that. I thought the initial line-cross was fine. The wide shot was so wide that the two characters were not so much left and right of frame as both in the middle, and being virtual silhouettes gave them a degree on anonymity.

I agree about using the sets and the landscapes. And all so pleasantly static. No wobbly-vision anywhere.

Pat Heigham

It’s necessary to start a scene (or new set) with a wide, so that the audience gets the geography in their minds.

I once worked with a Director, who started with the sensible wide, then cut the take a few dialogue lines in. When it was pointed out that the scene had not been played through, he said that he would never use the wide beyond that point. Saving expensive celluloid in those days – now with electronic capture, it plays for ever!

When a small continuity error is pointed out, often the retort is: “If the audience spots that, they’ve lost the plot” i.e. the story/dialogue lacks strength enough to engage attention, thus the latter wanders away from the essential scene. Now the facility of pausing a DVD or off-air recording is possible, the home viewer can indulge a passion for picking holes!

Large screen image size ([discussed elsewhere]): On a visit to IMax, a trailer was run, cutting from a wonderfully impressive wide shot to a CU of a head! No-one was ready for a face being three double-decker buses high!

Two people in the front of a car. Can be shot from behind, but if faces seen from front, then the line is between the two heads. (ear to ear?). Window mounted cams, positioned slightly forward, provides the necessary geometry, and can now be seen used extensively on the reality police car programmes, with mini-cams fitted inside the cabin.

Movement direction on screen: A Western? e.g. bad guys being chased by the sheriff’s posse. Both bodies should be shown travelling in the same direction, say R-L. If it’s edited that one lot are going the other way, then either they are approaching each other, (maybe riding to cut them off at the gulch!) but that

I remember Mike Dormer, and agree that he was a lovely chap to work with. The best thing about BBC Staff directors was that there was production training in place, so a certain equal standard was achieved. I have always to thank the BBC for my technical training, as it proved very pertinent to my subsequent freelance career and the work I secured.

Food for thought!

David Beer

I agree with all these comments. Quite a few years ago, I was working on a “Question Time” OB in Liverpool cathedral and when the director was giving us his pre-rehearsal chat he said: “…I don’t want static shots on all the CU’s, just keep a little bit of movement on them..”. I couldn’t help myself, replying, “Are you serious!”. “Yes”, he said, “I want it to look a bit more rough round the edges than usual”. Brian Parker, ex-TC, whispered in my ear, “We’ll just turn the frictions off on the panning heads then!” I don’t think it caught on.

Tony Grant

Oh dear, re-inventing the broken wheel. Do you remember “Monitor” with Jonathan Miller in B&W in the 1960s when the editor/producer/director decided that they should cut to BCUs of ears, hands, mouths during interviews, on the pretext that when you are talking to someone you often look at other parts of their anatomy than their full face. It took a lot of ‘persuasion’ to convince them that should viewers wish to do so, then the answer was to provide a shot sufficiently wide to include whichever portions of anatomy they thought may be ‘relevant’ to the topic, and leave the viewer to do their own study of ears, nostrils, etc. otherwise, the topic under discussion becomes irrelevant as the viewer is busy wondering what a tight shot of a spectacle frame has to do with latest production of “The Tempest” in the West End: in fact the more esoteric the discussion, the more frustration/incomprehension is propagated by this questionable ‘technique’.

Mis-framed/poorly-lit/wobbly shots detract from dialogue, and build frustration in the viewer. If this is the result a director wishes to achieve, then fine. When faced with requests for wobbly shots to enhance the ‘immediacy’ of a scene, I suggested that they were insulting the actors, whose job was to interpret the script to convey the dramatic impact of a scene, and any decent actor/director relationship could do this without recourse to confusing the viewer with poorly framed/constructed shots. Would they be satisfied with half-finished, untidy costumes, woefully inadequate make-up, wobbling scenery, etc? Of course now, from my elevated position as a fully retired boring old fart, I can say this, but I appreciate that in today’s world, freelancers cannot alienate their source/s of employment with such intelligent observations.

I leave you with one positive I received after working on PSC for several years. A “Panorama” producer who had started out wet-behind-the-ears in Lime Grove in the days of “Breakfast Time” took me aside after a shoot and said could I pass on to all the crews there how much he appreciated the help, advice and support we gave him and his colleagues in their early days, as it was the best possible training anyone could receive.

Roger Bunce

Dear Tony,

Those dramas – Surely a man of your background would have shot the whole scene in a single Jim-Atkinson-style developing shot? No need for any editing. I remember when TVC cameramen first went over to N&CA, and were horrified to find editors were using the reframes between their careful composed shots – because it was more exciting!

Dear Hugh and Albert,

I do not believe that my enjoyment of “Shetland” would be in any way reduced by better picture composition. It’s perfectly possible to be edgy and well composed.

A philosophical P.S.

Once upon a time, we watched 405-line television on a bulbous 9-inch screen (with or without a giant liquid-filled magnifying glass). Of necessity the camerawork involved lots of Close-Ups, MCUs, Tight 2Ss, etc. because there was no hope of seeing facial expressions in a fuzzy Wide Shot. Thus our television camerawork conventions were established.

Over time, the resolution improved – 625-lines, Colour, Wide Screen, Hi-Def, etc. and domestic screens became much bigger. Increasingly we could get away with a more cinematic style of camerawork, fewer Close-Ups, more action happening in the Wide-Shot. (One of the issues I’ve noticed on “Shetland” is that they’re still trying to use televisual framing conventions (e.g. tight, over-shoulder, dirty singles) but have no idea what to do with all that extra space created by the wide-screen format.)

When television screens are the size of a living room wall, will we still cut into Close-Ups? Wouldn’t a face the size of your room be somewhat nightmarish? Will we cut? Maybe we’ll shoot whole scenes in a single Wide Shot: the actors moving about in a stationary frame, and viewers will watch it like a theatre performance, choosing which face they want to look at, and when. And maybe we’ll need that fade to black between scenes.

BUT –

At the same time that domestic screens are getting bigger and clearer, increasing numbers of idiots are watching stuff on their mobile phones – on a screen even smaller than the old 405-Line one. They don’t even have a giant liquid-filled magnifying glass! Will we need to shoot two versions of every drama, one for big teles and one for mobiles? Will Cameramen need marking on their viewfinders, to show whether their framing is ‘Mobile Phone Compatible’?

I’m glad I retired!

Hugh Sheppard

Twice in the early 1960s I was on a camera for Michael Leeston-Smith. Both times he broke rules galore and we all hated him for it, and both times he won the Prix Italia. It gets called pushing the envelope and it’s all part of the learning curve of how television evolves. I don’t think we’re that far apart.

Roger Bunce

Wow! He was pushing the envelope on a learning curve! That must have ticked all the boxes he was thinking outside of, going forward.

As I’ve said, there’s no rule that says you can’t break the rules – so why would you hate anyone for doing so? Personally, I’ve always enjoyed breaking the rules, when trying things that are genuinely new and original. Sometimes they work, sometimes they don’t, but the experiment is always fun. You can enjoy the ride, and people must have the right to fail. But then I’m just a big kid who likes playing with new toys.

I’m less keen on recycling old ideas, especially those which didn’t work last time, and haven’t worked this time, either. That’s not even a learning-straight, let alone a curve.

The trouble with being an old geezer is that you’ve (probably) seen it all before. The learning has curved round so far that it’s become a cycle. Ideas come into fashion; go out of fashion, then come back in again (even the really bad ones). Every so often a bright young thing comes bouncing up, announcing a wholly new way of doing things. You smile politely – DO NOT say, “That’s what we used to do 20 years ago. It was crap, but you’re too young to remember.” – and try to be as helpful as you can. Your reward is that every so often a bright young thing comes bouncing up, announcing a wholly new way of doing things – and it really is – and it’s great, and a delight work on!

I remember thinking that the shots on ‘Utopia’ (Channel 4, 2013) were the last time I saw anything genuinely original; they had a strangeness consistent with the surrealism of the whole piece. But “Shetland” still looks more like accident than originality.

And here is what the DoP on Shetland (the former one) had to say on ‘Facebook’ – where several people have been having a go at him. (In my case, before I realised that he was in that Facebook group – Oops!) A pretentious, self-indulgent reply from a Director with a double-barrelled name doesn’t surprise me too much. But this, from an alleged industry professional craftsman, is more worrying.

This is his response to comments about negative looking-room, and crossing-the-line.

“… Re negative: the director and I like compositions like that. Re: “the line”: all things being equal we will stick with conventional screen direction… however not if it significantly compromises the shot. I won’t shoot some boring shot with no depth and awful light just to keep on the right side of the 180 degree rule … Which to be honest would be better described as simply: don’t create edits that introduce unwanted confusion. This whole thing of “the line” strikes me in most situations as needlessly slavish and in many cases inaccurate anyway (where is “the line” for two characters in the front seats of a driving car?) We’re not dealing with audiences new to the concept of cinema. The only people I ever hear complain about this tend to be people in the industry who grew up obsessing about “the line” and it’s all they can see about a cut. The public just watch the story. The only situation in which I’ll almost always stay on the same side is shots with no visible edge of the other character… if it’s intercut clean CU in a two hander and both characters are looking the same way then that is probably where I’d say it’s confusing…”

One of the other ‘Facebook’ critics described the situation as a “…Director’s Wankfest…”. Crude, but pithily accurate.

Alec Bray

Roger Bunce quoted the director of “Shetland as saying”:

“…Where is “the line” for two characters in the front seats of a driving car?…”

Obviously he hasn’t got a clue. The line here is the same as two people walking towards camera and then away from the camera – here the 180 degree change is acceptable as the viewer can replicate the camera shot as the car passes them.

and :

“…I won’t shoot some boring shot with no depth and awful light just to keep on the right side of the 180 degree rule…”

‘scuse me – no portable lights, fillers, camera headlights, reflecting material held at an angle to reflect the sun? Oh my oh my. Quite happy to make the viewer jump as people switch sides of the screen for no reason!!

John Barlow quoted the director::

“…make the characters appear uncomfortable in their environment;…”

Funny, I though that directors like Hitchcock, Ridley Scott and countless others managed to do this and maintain looking room, headroom … and the line!

Barry Bonner

I find the wrong side of frame and the bottom of frame shots on “Shetland” really annoying let alone confusing. I can’t understand what the director is trying to convey, apart from maybe he’s trying to be “trendy” – whatever that means. Also the preponderance of shots containing a foreground object e.g. a potted plant, gatepost etc. in focus and actors in the background out of focus in many TV shows. My eyes don’t do that when I’m listening or watching people so why do it? I’ve often had doubts about actors that become directors, having worked with a few.

Lee Haven Jones, the current director of Shetland said this in an interview on the “Wales Online” site…

Q: You are also training to be a director. Do you think this will take over from acting?

A: My intention now is to combine both acting and directing – I want to have my cake and eat it!

Q: What made you decide that you wanted to direct as well as act?

A: I always intended to become a director. I just got lured into the acting profession after I caught the bug when I was at RADA. I decided to go there to learn about the process of acting because the main concern that actors have with some television directors is that they know very little about acting as a craft. I didn’t want to be one of those.

So now you know!!

Albert Barber

I’m not sure you are going the best way about this. There are a number of starting points, but to rubbish isn’t one. In my view there are two:

- Storytelling, and

- Forget your audience at your peril.

—————-

Roger Bunce

O.K. What Happened?

I’ve just seen the next episode of “Shetland”, I didn’t notice a single crossed eyeline, and the framing was all pretty reasonable. Has the fad passed that quickly?

Roy Bailey

Same Director, Roger?

Roger Bunce

Roy! You’ve made me search all the way through the credits – only to discovered that the Director’s credit was at the beginning – not the end. For a moment I thought he’d asked to have his name taken off!

But – Yes – it was a different Director.

I’m surprised they shoot it episode at a time.

Barry Bonner

Just caught up with Episode 4 of “Shetland”…properly directed by Rebecca Award. No silly miss-framing or blurred shots. I wonder if she’s related to the affable Jimmy Award?

Dave Plowman

I must admit to not really noticing anything odd before it was mentioned here, so watched tonight’s “Shetland” all agog.

Only thing I thought is they made a bit too much use of their drone camera. Understandable if you’d paid for a real helicopter.