My Working Life

by John Summers

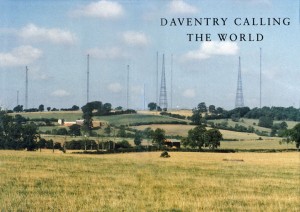

I was born on 25th October 1925. I lived in Carshalton, Surrey, with my Mum and Dad, who was a hotel manager, and elder brothers George and Ron. After infants and primary school education I went to the Alfred Sutton Central School in Reading from 1938 until 1942. I started this school at thirteen years and I left at sixteen and three quarters, having gained my School Certificate. After being turned down by the Post Office as an engineer, I got a job at the Pulsometer Engineering Co., along the Oxford Road. My pay was twenty-five shillings (£1 – 25p) a week for a forty-eight hour week. I started there in October 1942, just after my seventeenth birthday, and was employed as an office boy. Work would start at 8.30am and finish at 6pm, with an hour off for lunch. I would get the boss’s tea, morning and afternoon, open and check the morning mail, type some standard letters, and run messages! I had made an application for a job a year earlier to the BBC, asking for work in the Engineering Dept., but they wrote back saying that their were no vacancies at the time. My eldest brother George already worked for the BBC, and was at Daventry Transmitting Station. The Second World War had started and he was involved with a Radar system, known as Gee, which was a highly secret method of guiding our bomber planes to targets over Germany. Because he was doing this work, he was not called up for military duty. His BBC career had started in Television at Alexandra Palace, before the war.

I was born on 25th October 1925. I lived in Carshalton, Surrey, with my Mum and Dad, who was a hotel manager, and elder brothers George and Ron. After infants and primary school education I went to the Alfred Sutton Central School in Reading from 1938 until 1942. I started this school at thirteen years and I left at sixteen and three quarters, having gained my School Certificate. After being turned down by the Post Office as an engineer, I got a job at the Pulsometer Engineering Co., along the Oxford Road. My pay was twenty-five shillings (£1 – 25p) a week for a forty-eight hour week. I started there in October 1942, just after my seventeenth birthday, and was employed as an office boy. Work would start at 8.30am and finish at 6pm, with an hour off for lunch. I would get the boss’s tea, morning and afternoon, open and check the morning mail, type some standard letters, and run messages! I had made an application for a job a year earlier to the BBC, asking for work in the Engineering Dept., but they wrote back saying that their were no vacancies at the time. My eldest brother George already worked for the BBC, and was at Daventry Transmitting Station. The Second World War had started and he was involved with a Radar system, known as Gee, which was a highly secret method of guiding our bomber planes to targets over Germany. Because he was doing this work, he was not called up for military duty. His BBC career had started in Television at Alexandra Palace, before the war.

In April 1943 I received a letter from George, telling me that he had written a memo to the Engineering Establishment Officer, BBC, in London, telling him about his brother wanting a job. E.E.O. replied to George, suggesting that I re-apply. George’s letter to me enclosed the memo, and Geo gave me explicit advice (!) on how to apply. He didn’t want me to muck it up! My application was followed by an interview in Reading, and I was offered a job as Youth (Transmitters), at Reading, at a weekly wage of £1.19.0, plus 4/6d Cost of Living Bonus (a total of two pounds seventeen and halfpence less tax!).

So my career with the BBC started on the fourteenth of June 1943, at Reading “H” Group. It turned out that my station at Reading was a secret one. It had been realised that the German bomber planes used our big National Radio transmitter stations as “beacons” and could navigate by them, as they knew where the stations were. A counter-strategy was employed whereby the whole of the British Isles was covered by nearly a hundred small (100 watt) transmitters, all transmitting the same program (BBC Home Service). When the bombers came over, the main big transmitters went off the air, but the little 100w H Group Stations carried on, so listeners did not lose the program. The German bombers then would pick up very weak signals from scores of transmitters all over the place, and could not use them to navigate. Another use for the H Group Stations, which luckily was never needed, was to be a local area transmitter for military use, should the Germans invade us.

There is a strange history associated with Reading H Group. It was first located in the middle of Reading, above a wartime restaurant, known as “The Peoples Pantry”. Reading was very lucky during the war. Although we heard the German bombers going over us nearly every night, on their way to bomb London, we never had an air raid. Except once. One Wednesday afternoon, a lone German bomber dropped a bomb on Reading, and then proceeded to fire his machine guns along the Oxford Road. I heard this happening whilst working at “the Pulsometer.” Miraculously the bomb hit the H Group station, went straight through the EiC’s chair in his office (he wasn’t sitting in it at the time), but it exploded below in the restaurant that was crowded at the time, killing many. The engineers above – probably only two or three at the most – unbelievably were unharmed, but had to descend into a terrible scene of horror and carnage. The bomber could not have deliberately bombed the H Group; he was probably damaged, and wanted to get rid of his bomb to lighten the load. I believe that later our fighter planes shot it down.

All this happened before I joined. The H Group transmitter was re-located at 51, Christchurch Road, Reading, in the garden of Mr. Sutton, of Sutton’s Seeds (Reading). It was the life of Riley -our transmitter was a box about the size of an average radio of those days. We just had to switch it on in the morning, switch it off at night, and listen to it all day running the Home Service. So long as it worked nobody worried. We worked three shifts, day (9am – 5pm) evening (4pm – 10pm) and night (10pm – 9am) . We had a small kitchen where we prepared our food, and we could go out into Mr. Sutton’s garden, with his permission, to help ourselves to fresh fruit. On the night shift we brought our lilos (airbeds), and slept till about half past five in the morning. Sometimes we had to do tests. London would send us a series of tones (frequencies) at a set time, in the middle of the night, at a pre-determined level. We would have to measure the level of each of these tones, to determine the line loss, and enter the results in a logbook. This process was called “squeaking the line”, and not infrequently we would sleep through the test period, and have to make up figures in the morning for the log!

I suppose this lovely life couldn’t last forever, and in December ’43 I was sent on a three month Training Course. I was to have a general training at Maida Vale Studios, London, and lasting one month, then continue at Droitwich (Long Wave) for specialist training in Transmitters for a further two months. Failure to reach a pass mark in this training course would result in termination, so we all worked very hard! I completed, and passed the course, and in April ’44 I was transferred to Daventry, as a fully-fledged Technical Assistant (Class 2). This was a very convenient transfer, as my big brother George was also there. I worked on Senders (transmitters) four and five. These were very big, short wave transmitters, maybe fifteen yards long with water-cooled valves.

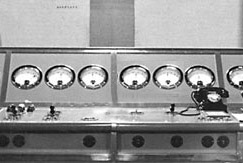

A lot of new work, and responsibilities were now mine. Again, this was to be shift work, with the same times as at Reading. The transmitters were in pairs, with an engineer on each. We had a chart telling us what times the transmitters came off the air, and what time, and the frequency that they were to come up on next. In twenty-four hours, I suppose each transmitter had about eight changes, so each shift had two or three. First, when doing a change you had to listen for the end of the program on your headphones. This was complicated by the fact that the program might be in Indian, or Egyptian, or any other  strange language! The clock was a good indication, as you knew when the transmitter was scheduled to come off the air. At the right moment the first thing was to take off the extra high tension voltage (10,000 volts), then the lower the other voltages, then take the valve filament voltages off, and then finally switch off all the motor generators, and take the power factor condenser out. When everything was switched off, it was safe to open the interlock, and go inside the transmitter. With a spanner, various alterations had to be made inside, so that the transmitter would work properly on the next frequency. Sometimes a motorized turntable would be operated, to change the internal circuitry of the transmitter.

strange language! The clock was a good indication, as you knew when the transmitter was scheduled to come off the air. At the right moment the first thing was to take off the extra high tension voltage (10,000 volts), then the lower the other voltages, then take the valve filament voltages off, and then finally switch off all the motor generators, and take the power factor condenser out. When everything was switched off, it was safe to open the interlock, and go inside the transmitter. With a spanner, various alterations had to be made inside, so that the transmitter would work properly on the next frequency. Sometimes a motorized turntable would be operated, to change the internal circuitry of the transmitter.

Everything that had to be done was written down on the crib card, and this was meticulously carried out. It was not unknown for this crib card to be temporarily mislaid, causing quite a bit of panic! Because of the high power involved, the output valves some five feet tall had water jackets to cool them. Sometimes there would only be fifteen minutes between wave changes, so you had to be quick and accurate, to get everything done. When this job was completed, the transmitter had to be powered up again, on the new wavelength (frequency). The meters all along the transmitter bay had to be inspected, as this was being done, to make sure all was well. If some part of the wave-change had been done incorrectly, then the meters would indicate trouble. This would involve taking off all the high voltages, nipping inside the transmitter, and making the necessary change. Some frequencies were trickier to set up than others were, but experience soon taught what was  necessary. With a bit of luck, your mate on the other transmitter wasn’t doing a wave-change at the same time, so could offer advice (!). The final operation was to apply the EHT voltage. This was done very carefully, watching the ammeters for troubles. It could be that sometimes a very slightly incorrect angle of a bar setting could cause spectacular trouble – a flashover! This was the effect of lightning, where the EHT voltages would cause a big, noisy spark that would only stop when you took the volts off. Sometimes it was caused through leaving the spanner in the transmitter; sometimes not fully tightening a nut would be the problem.

necessary. With a bit of luck, your mate on the other transmitter wasn’t doing a wave-change at the same time, so could offer advice (!). The final operation was to apply the EHT voltage. This was done very carefully, watching the ammeters for troubles. It could be that sometimes a very slightly incorrect angle of a bar setting could cause spectacular trouble – a flashover! This was the effect of lightning, where the EHT voltages would cause a big, noisy spark that would only stop when you took the volts off. Sometimes it was caused through leaving the spanner in the transmitter; sometimes not fully tightening a nut would be the problem.

It did not take too long before I learned all the likely problems and answers. Once the transmitter was up and running all that was needed was to listen to the program on headphones, and regularly check the various meters, until it was time to do the next change! Every so often, perhaps on a loud passage of music, a flashover would occur. It might be half past three in the morning, with eyes glazed, and almost dropping off to sleep, with Indian music wailing in your ears, you’d suddenly be brought back with an almighty noise and a great surge of flashing light coming from somewhere inside the transmitter. Before you knew what you were doing, you’d be on your feet leaping to yank the lever to take the EHT off, and then slowly creep it back on again. With a bit of luck the transmitter would only be off the air for 15secs, but if for any reason we were off for more than a minute, we had to tell the control room, so that an apology could be made from the Studio in London.

What a change all this was for me. In three months I had gone from helping look after a  nice quiet 100-watt transmitter, requiring no changes, to this hectic life, being in charge of a 30kw monster, requiring constant attention. I should add though, if ever any of us was in real trouble we had a Senior Maintenance Engineer who would take over. If we called on him, and the trouble was found to be an error on our part, he was unmerciful. But sometimes things just broke down, and that could be difficult for the SME. His responsibility was, with his assistant. to get it working again as soon as possible – seconds being counted! Furthermore he was responsible for all eight transmitters in the Daventry Main Hall! His was a real nail-biting job. My S.M.E. was a guy called Harry Masters (Mr.!). His assistant was a pleasant man, Mr. Sutton, (known by all as “Sutt.). Harry Masters would make a tour of the transmitters, at the beginning of a night shift, and ask each of us “engineers” how we wanted to spend our hour off duty. We were allowed this time for breaks, nominally to have a snack in the middle of the night, and breakfast in the morning. If we told him that we wanted our hour off for rest, we had to say when it would be taken, and he would check that we took no extra time, and that we didn’t go to the canteen at all during the night! What a life!

nice quiet 100-watt transmitter, requiring no changes, to this hectic life, being in charge of a 30kw monster, requiring constant attention. I should add though, if ever any of us was in real trouble we had a Senior Maintenance Engineer who would take over. If we called on him, and the trouble was found to be an error on our part, he was unmerciful. But sometimes things just broke down, and that could be difficult for the SME. His responsibility was, with his assistant. to get it working again as soon as possible – seconds being counted! Furthermore he was responsible for all eight transmitters in the Daventry Main Hall! His was a real nail-biting job. My S.M.E. was a guy called Harry Masters (Mr.!). His assistant was a pleasant man, Mr. Sutton, (known by all as “Sutt.). Harry Masters would make a tour of the transmitters, at the beginning of a night shift, and ask each of us “engineers” how we wanted to spend our hour off duty. We were allowed this time for breaks, nominally to have a snack in the middle of the night, and breakfast in the morning. If we told him that we wanted our hour off for rest, we had to say when it would be taken, and he would check that we took no extra time, and that we didn’t go to the canteen at all during the night! What a life!

My brother George was in digs in Daventry but I preferred to be with all the young rogues in the BBC Hostel at Welton Manor. A most aristocratic lady, named Mrs. (Paddy) Foy ran this. She was tall, and very elegant, and I suppose in her early forties, and to give you some idea of her character, I will tell you that nobody addressed her by any other form, than “Mrs. Foy”. I don’t think anybody used her Christian name. There would be about two dozen of us staying in the hostel, mainly young men, but a few young lady engineers. The dining room was very pleasant, and we ate from superb long oak tables (about four were there), with no tablecloths. We lads would all rush down stairs when the dinner gong sounded, in order to avoid sitting at Mrs. Foy’s table. She always ate with us, but she was such a lady, that only polite conversation was permitted at her table. She would always enter the dining room about three minutes after the gong had sounded, and she would sit in her usual place, at the same table, usually deserted, often with the other tables full. When I think back, our behaviour was absolutely awful, but she was a perfect brick. She never complained, or took it out on any of us. If anyone was ill, she always took the greatest care of him or her. She was really wonderful, and even now I feel shamed when I think of our behaviour. It was usually only the latecomers, who could find no other table free that joined her.

The house as a whole was very pleasant, being set in its own grounds, and well in the country. The dormitories all had double bunk beds, three or four to a room, and I always went for a top bunk. You had to enter the bedroom quietly during the day, as there would be others who had worked a night shift, trying to sleep! All days of the week were worked, and public and Bank holidays had to be worked as well (including Christmas Day), if it was your shift day. A day off in lieu (doil) was given for each public holiday actually worked. The shift pattern was arranged so that every other week you finished work on Friday after a night shift, had Saturday and Sunday off, and returned to work on Monday, for an evening shift. This gave a long weekend, and I could catch a train from Leamington Spa to Reading every so often. I used to bicycle from Daventry to Leamington, and leave the bike in the station.

I was nineteen by now, and just days before my twentieth birthday, I saw an advert on the notice board for an engineer based in Middlesborough. When I try to think back now, and understand why I applied for the job, I just can’t come up with a logical reason. It certainly wasn’t a good career move. I can only think that I saw it as an adventure, something different. Middlesborough was another H Group Station, and I found digs nearby. Within two weeks of arriving, I had written a memo to EEO, asking for a transfer to any southern station, and of course it was refused. It was a very industrialized area, with a permanent and persistent acrid smell coming from the ICI factory. I was amazed to see ragged children playing in the streets with no shoes on their feet because their parents were so poor. I don’t remember feeling particularly unhappy, but everything was so different to what I was used to. About the only thing I can recall about my digs is connected with food. One day, my landlady put my lunch on the table, and as it looked different, I asked her what it was. She smiled, and said to eat it up, and she would tell me afterwards. I thoroughly enjoyed the meal, but afterwards she told me it was…… cows udder! Ugh!

EEO must have looked on my application kindly – I might have remained there for years, but eight months later, in July ’45, I was transferred back to.. .Daventry! Surprise, Surprise!

So, back I went to Welton Manor, and Mrs. Foy. To complete the circle, I found myself back on the same two transmitters, Senders four and five, and yes, the same SME. So there I was back in the old routine, with all my mates again.

One thing that remains in my mind from this time, is that early one morning, towards the end of my night shift, half dozing, with my headphones over my ears, I heard the voice of General Eisenhower announcing D Day, the long awaited invasion of Europe!

I think that fate now took a firm hold of me, as it seemed I was quite incapable of doing the right thing by myself, and dragged me in the right direction. The EiC was, as I have said, Douglas Birkinshaw (Mr. Birkinshaw to me!), and he had been told to prepare for the re-opening of the Television Service, as it looked as though the end of the war in Europe was in sight. He had arranged for a number of ex television people to be transferred with him to Daventry, at the beginning of the war, George amongst them, and now he began asking them if they would like to return with him to Alexandra Palace, when the Television Service resumed. I applied for transfer to the London Television Service, on my twentieth birthday, and six months later, I received a memo transferring me to Alexandra Palace, as from the 6th May 1946, just under three years from joining the BBC at Reading.

I did not know it then, but television was to be my work for the next forty years, until my retirement. It seems that fate was determined to get me there, in spite of my own actions! Everything, looking back now seems to have conspired for this to happen, and I must own that the next forty odd years of my life were destined to be the most happy, exhilarating, demanding, exiting, and wonderful that can be imagined.

Because there was a good train service from Reading, I decided to move back home, and travel to work. I would usually stay at the “Queen’s”, walk to the Station, and catch the 7.15am train to Paddington. Then the Underground to Wood Green, then a bus up the hill to Alexandra Palace, where I would arrive by 9.00am, to start work. At the end of a working day, the reverse, bus, underground, catch the 11 02pm train from Paddington to Reading, walking back to the Hotel, and arriving at about half past twelve in the morning. This wasn’t as bad as it sounds, as I worked a shift of seven days a fortnight!

Our shift pattern, known as the AP shift was:

We started at 9.00am, and finished at 10.30pm, a thirteen and a half hour day. As you can see, if Thursday and Friday were worked together, one week, then Saturday and Sunday were off. The reverse happened the next week. Everyone thought it was a good shift pattern. There were two shifts, when one worked the other had that day off, and vice versa. This pattern worked well for me, but when I had to work two days on the trot, getting to bed at half past twelve in the morning, and getting up again at six was too much! Sometimes on these occasions I stayed overnight with two mates who had a flat in Muswell Hill, Kenny McCready and Bob Gray. As an alternative, I would kip down for the night in a dressing room, to be awakened at seven in the morning by the happy voices of the “cleaning ladies”!

We started at 9.00am, and finished at 10.30pm, a thirteen and a half hour day. As you can see, if Thursday and Friday were worked together, one week, then Saturday and Sunday were off. The reverse happened the next week. Everyone thought it was a good shift pattern. There were two shifts, when one worked the other had that day off, and vice versa. This pattern worked well for me, but when I had to work two days on the trot, getting to bed at half past twelve in the morning, and getting up again at six was too much! Sometimes on these occasions I stayed overnight with two mates who had a flat in Muswell Hill, Kenny McCready and Bob Gray. As an alternative, I would kip down for the night in a dressing room, to be awakened at seven in the morning by the happy voices of the “cleaning ladies”!

So, what was working in TV like? On my first day, 6th May 1946, I came out of Wood Green underground station, crossed the road, and caught the little single decker bus that goes up the hill through the Gardens, to Alexandra Palace. It was (and still is) a lovely setting with great views across London, and many landmarks could be picked out. Alexandra Palace was a Victorian building, that had suffered a severe fire, and although the shell of the structure had survived most of the interior was gutted, and abandoned. The most noticeable thing about the building was the high Television Transmitting Aerial, sitting on top of one of the towers. We had this tower, which housed the offices, and quite a stretch of the building that fronted the road. This is where the two Studios were, Studios A and B. Across the road was “The Dive”, a super pub where we could have a pleasant lubrication at lunchtime.

Leaving the bus, I walked up to the front entrance, mounted two or three steps, pushed open the heavy copper lined doors, and walked across to the reception desk. I asked to see Mr. Baker, A.E.i.C., and went up in the little lift to his office. After a brief interview and lecture, I was told to report to Mr. Henry Whiting, S.Tel.E. in charge of Studio A. Downstairs again, to the first floor, along the passage, and through the whitewashed door, with a little “porthole” to the Studio.

It was very hot, and very crowded, and a rehearsal was taking place, I reported to Mr. Whiting, who asked me what I wanted to do – sound or cameras. I thought a cameraman’s job sounded glamorous so I chose the latter. He just said, “There’s a boom – you’re on sound! I climbed up onto this rickety device on three wheels, put headphones on, and with no training whatsoever started to swing the microphone over the heads of the artists. It’s a wonder I didn’t hit any of them with it – but soon the Sound Supervisor was complaining he couldn’t hear anything. When I brought the mike closer the Director shouted, “Get that ****** microphone out of shot! So it went on like this for the rest of the day. The next morning Mr. Whiting came up to me and said “Summers – report to Mr. Ted Langley (Senior Cameraman) – you’re on cameras!

All technicians would wear headphones during rehearsals and transmission so that they could hear the director’s instructions, and also the vision mixer telling when a camera was on air. The sound supervisor could give instructions to his boom operators, and the “racks” engineers were able to communicate with the camera-men on technical problems.

All technicians would wear headphones during rehearsals and transmission so that they could hear the director’s instructions, and also the vision mixer telling when a camera was on air. The sound supervisor could give instructions to his boom operators, and the “racks” engineers were able to communicate with the camera-men on technical problems.

I became a camera assistant under Ted Langley (Crew 2), Senior Cameraman of Studio A, Cyril Wilkins being the Senior Camera-man in Studio B. A camera crew consisted of seven members, four to operate the cameras, and the other three to track the two mobile ones mounted on dollies, and to clear camera cables from tracking lines. There were a few girls on camera crews, Bimbi Harris for one, and they got their hands just as dirty as the lads, clearing the camera cables. If a camera hit a cable, it gave the shot quite a jolt! The sound crew, under the Sound Supervisor consisted of four technicians. Sound pick-up was normally via two sound booms. A “grams” operator also came under the Sound Supervisor, and was responsible for inputting any recorded sound, usually via a gramophone. The output from the cameras, and also the telecine machine, and any outside broadcasts were visible in the production control room. However, there was not the facility of a separate monitor for each source, as there would be later in television control rooms. Only two monitors were available, one for transmission, the other to pre-view any selected source. This was the job of the Vision Mixer, nearly always a girl, who would cut or mix between the different cameras, and immediately switch the next camera’s picture to preview, so that the director could check that the shot was set up correctly.

The four cameras each had two lenses, six-inch focal length, and maximum stop f/3. One  was to project an image onto the Emitron pick-up tube that converts the light into an electrical signal; the other was part of the cameraman’s viewfinder. This lens projected an inverted colour image of the scene onto a ground glass screen about four inches by three, enabling the camera-man to focus, and compose his picture. The depth of field was extremely short, as when taking a medium close up (MCU) at about five feet from a subject, the eyes would be in focus, but the tip of the nose would be blurred! Once a camera was switched on in the morning, it would give a continuous output. The electrical signal from the camera would be transferred to the technical area (racks) via a two inch diameter cable. Once in racks, the picture would go through a manual process called “tilt and bend”, in order to minimise the spuriously generated signals that degraded it.

was to project an image onto the Emitron pick-up tube that converts the light into an electrical signal; the other was part of the cameraman’s viewfinder. This lens projected an inverted colour image of the scene onto a ground glass screen about four inches by three, enabling the camera-man to focus, and compose his picture. The depth of field was extremely short, as when taking a medium close up (MCU) at about five feet from a subject, the eyes would be in focus, but the tip of the nose would be blurred! Once a camera was switched on in the morning, it would give a continuous output. The electrical signal from the camera would be transferred to the technical area (racks) via a two inch diameter cable. Once in racks, the picture would go through a manual process called “tilt and bend”, in order to minimise the spuriously generated signals that degraded it.

The pictures were of course in monochrome, and as no method of recording had been developed, all programmes went out live. The cameras and camera cables were extremely unreliable, faults being the normal order of the day. It was not unknown for three of the four cameras to need attention during a transmission, with engineers with soldering irons, working on the equipment only a few feet away from performing artists. I can recall doing a variety programme in Studio A one evening, and although we started the live transmission with four cameras, half way through three of the cameras had developed faults, and were un-useable, and mine was the only camera still working. It meant that quite a bit of improvising was necessary! The worst fault was losing talkback – you could no longer hear the director or vision mixer, so you could never be sure when your camera would be used. A red light would come on in the viewfinder when the mixer put your camera on air, and you had to cover the action as best you could. If a camera cable needed to be changed things became even more tricky, as it was essential to be as quiet as possible whilst the programme continued. Fitting the cable end into the underside of the camera was a chancy affair – if not offered up correctly, connecting pins would be bent, causing even more problems. Time pressures and the need to get cameras back into operation as quickly as possible did not help these operations!

Before rehearsals could start at 10.30am it was necessary for each camera to go through a lengthy line-up procedure. Each camera in turn would be set up squarely on to a test card, so that focus, camera limits (size of picture) and camera controls could be checked. This was done between nine and ten o’clock, allowing a half an hour refreshment break.

Before live transmissions started we rehearsed the same play day after day with different Directors. The play was called “They Flew Through Sand” and by the end of a month we could all say the lines as well as the artistes! When this training period was finished we went on air with live productions – in black and white. There was no way to record and edit programmes yet. We started live transmissions in June 1946, and They Flew Through Sand was one of the first productions to be transmitted. “Google” tells me that Kenneth More played the part of an RAF officer.

My job was dolly operator. The cameraman would sit on the “dolly”, a three or four-wheeled truck to enable a camera to track closer or back from a scene. A T/V camera (emitron) was mounted at the front and I would watch the cameraman’s finger like a hawk – and push or pull the dolly in our out as he waggled his finger. I can remember, later, when live transmissions had started working on a Mantovani band show. We were on air and I was watching Ted’s finger very closely indeed, as he always insisted, whilst tracking in. Suddenly I heard a gasp, and looking up I saw Mr. Mantovani glaring at me – I had run over his foot – and he wasn’t best pleased!

I can’t relate all the events that happened to me over the next forty years here, but I’ll write down some of the early funny ones occurring at Alexandra Palace that stick in my memory. I can vouch that they are all true, although some sound unlikely to modern ears.

I joined the Television Service in 1946, and became a “dolly operator” on crew 2, under Senior Cameraman, Ted Langley. He was a really macho type, and did much to create the prestige of camera operation in TV. He demanded 101% concentration from his trackers, and big close ups and fast tracks were his hallmark. He was a scourge to incompetent directors, and would sometimes become very exasperated with them. Once in a while he would get so annoyed that he would throw off his cans (headphones), and rush up the stairs to the control room, to give a luckless director a piece of his mind. We lads on the floor would push our headphones a bit closer to our ears so that we didn’t miss a word!

We were in Studio A rehearsing a variety program. A knife-throwing act had just finished on camera and we were waiting for the next turn to arrive. Ted leaned forward from his camera, and asked the knife thrower if he would throw at him. He agreed, and Ted replaced the lovely girl in front of the target and had five knives thrown at him – all landing behind Ted jolly close to his body. Can you imagine this happening today in T/V, with Health and Safety? Well nothing untoward occurred, and afterwards Ted got back on his camera, and we carried on rehearsing. Of course we lads were all very impressed with Ted.

The next day we were rehearsing a play. The action was supposed to take place in a hospital with a blood donor, and Ted set up on a still shot of blood dripping into the bottle. Although the scene in the viewfinder was up side down – it was in full colour. After a while it proved to be too much for Ted – he fainted.

It was Sunday morning in Studio A. Apart from me it was deserted. I was operating camera 4 that day and was the last camera to be lined up; the rest of the crew was down in the restaurant having morning coffee before rehearsals started. My emitron camera was set up with Test Card “C” in front of it. I had used my headphone lead to measure the distance from camera to the test card, and made sure it was squared up. The focus check had been finalised, and racks had said that I could mark in the limits. I had to remove the viewfinder ground glass screen, apply liquid soap from the gents, and use Bronco (hard) loo paper to wipe off the old limits. Back to the Studio, mark in the new limits with pencil, after inserting the glass screen and focusing the viewfinder. Being an optical viewfinder, the picture was up-side-down. Having capped up – covered the emitron pickup tube – I was just leaving the studio for a quick coffee, when Dickie Meakin came limping over to me from racks. His face was ashen, and what seemed unbelievable – he had a 3ft long spike sticking out from both sides of his blood-soaked trouser leg.

“I’ve had a terrible accident, see if you can get Nurse to come up and help me” I heard him say. With out any hanging around I rushed along the corridor, down the back stairs to her surgery. Nurse was sitting comfortably, sipping her coffee and reading the newspaper. “Come quick Nurse – Dickie Meakin has had a terrible accident!” I blurted out. Nurse looked at me calmly, glanced at her watch, and said “Tell Dickie I’ll be up in a few minutes”. I could not believe what I was hearing, but I was far too young and inexperienced to argue – I just dashed back as fast as I could to see how Dickie was. The studio was deserted – no Dickie. I rushed into racks, and there he was, sitting on the high chair, smiling. He saw the look of total disbelief on my face, and slowly pulled his trouser leg up, above his shoe, to reveal the latticework of an artificial leg! Using some stag” blood, and some white powder from makeup, old trousers from wardrobe, and a spike from the stagehands he had completely fooled me! I learned later that Dickie had been a fighter pilot during the war, and had lost a leg in action.

I wonder if anybody remembers Henry Caldwell’s production of Cafe Continental? It went out live on Saturday nights during 1947 – 53, from Studio A at Ally Pally. It was the first light entertainment show of BBC television, and had many top stars performing in it.

As the program starts the viewer seems to be in a moving taxi. It stops and we see out of the window the “Café Continental”. A Major Domo in uniform comes forward, salutes and opens the taxi door. We step out, walk towards the entrance and look at the billboard on the right of the Café entrance and read the names of the stars. Pere August comes through the Café door, welcomes us and beckons us to follow him into the Café. The program then continues with the cabaret. The end sequence is the reverse of the beginning; we leave the Café, look at the billboard once more, move back and into the taxi. You can imagine all the things that could go wrong (and they did!) with this opening and closing sequence to the program, all-live and on one iron man (non-tracking) camera.

Before going on air the painted plywood cut out of the side of a taxi interior (mounted on castor wheels) would be put in front of the camera. On cue the camera and the cut out pushed by a scene hand, would move sideways and then both stop opposite the Café entrance, simulating the taxi stopping. We would see the Major Domo through the window and he would step forward and open the taxi door. The taxi cut out is in two halves, joined in the middle. As the camera moves forward to follow, the scene hands pull the two halves of the taxi apart, to allow the camera through. After that it is simple. Go in, pan right onto billboard. Pan down to read names. Cue Pere to come out. Pan left onto him and follow him in. Cut to mainstage cameras and start the Cabaret with compere Helene Cordet. The ending was shot in the same way – camera on Café door, Pere says “Au Revoir – hope you enjoyed the show!” Pan right onto billboard, pan down names, pull back to marks on floor, hope the scène hands have got the cut out in front of the camera and on its marks, pull back to second mark to reveal (hopefully) the taxi window. Cue major Domo to step forward, salute, smile and wink as he closes the taxi door. Now for the really tricky bit! A scene hand would be lying on the floor, in front of the camera, out of shot. He has a ladies long white evening glove over his hand and lower arm, and on cue he reaches upwards, grasps the tassel of the window blind, pulls it down to reveal “The End” tastefully written on it. We did this opening and closing sequence for every “Café Continental” and I can’t remember it ever going completely smoothly. You think what could go wrong attempting this routine, and I assure you that it happened at some point.

Perhaps the worst mistake occurred in the end sequence. The long white evening glove was necessary to hide the hairy, tattooed arm of a burly scene worker. On one occasion the arm came a shade too high…..I can still hear Henry Caldwell’s irate voice coming down my cans, using some very choice expletives!

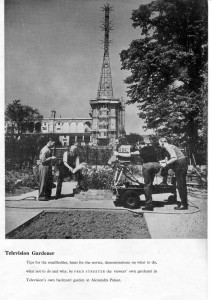

In the early days of AP we would sometimes do a “Local OB” from our garden in the grounds of Alexandra Palace. It was about 500 yards from the building, and we fed a camera cable from racks, through a duct under the road to the garden. We rigged one emitron camera, mounted on a tripod set on a three-wheeled wooden dolly, and we would take all morning to get rigged, tested and lined up. We would go “live” on air at three o’clock, without a rehearsal, but this was no problem because the programs were very simple, with just a presenter talking to camera, with demonstrations, and the director would talk us through the action.

In the early days of AP we would sometimes do a “Local OB” from our garden in the grounds of Alexandra Palace. It was about 500 yards from the building, and we fed a camera cable from racks, through a duct under the road to the garden. We rigged one emitron camera, mounted on a tripod set on a three-wheeled wooden dolly, and we would take all morning to get rigged, tested and lined up. We would go “live” on air at three o’clock, without a rehearsal, but this was no problem because the programs were very simple, with just a presenter talking to camera, with demonstrations, and the director would talk us through the action.

I was the cameraman on one occasion, and I lined up a head and shoulders shot of the presenter, who was standing in front of a demonstration table. The opening music faded, and I heard over my cans (headphones) the continuity announcer, Winifred Shotter introducing our program. “Cue Bill” said the director, and we were off. “This afternoon I’m going to show you how to hive wild bees” (just the sort of thing your average viewing gardener needs to know!). Bill Gamblin continued, “First of all you must put on fully protective clothing”. He then proceeded to put on protective coat, headgear, veil and gloves. Then he reached under the table, saying, “ I have here a skep of wild bees”. He promptly turned over the basket of bees onto the table. In an instant 10,000 bees were swarming round and about us. I could feel them crawling about on my focusing hand and bare arm. I pushed my face closer into the viewfinder visor to prevent any bees getting in there! I was only some six feet away from the angry swarm and felt somewhat uncomfortable. “First of all you must identify the queen bee,” said Bill. “I’ve marked her with a spot, and you can see her here”. “In you go,” said the director over my cans. In we went – close up of queen bee at limit of focus – about 18 inches away, my viewfinder showing a mass of bees, with a big bee with a yellow spot marked on its back in the middle. The noisy humming was now intense, and I could feel the wretched bees everywhere on my hands and arms and the back of my head. After some further talk from Bill I thought that we had seen enough of the queen, and I signalled to Ronnie Koplick, my tracker that day, to pull back. No response to my finger. Frantic movement of finger – but still we do not move. In desperation I pulled my head out of the viewfinder to see what the problem was. No Ronnie to be seen behind the dolly but there he was on the far side of the garden by the fence, with the floor manager and make-up girl, sheltering from the bees!

Well I guess we got through the program somehow, without anyone being stung. When we had finished and were packing up “Sutt” (Mr. Sutton – Stel.E), came down to see that all was OK. He hadn’t been in the garden for more than a minute, when a bee came zooming onto his forehead, and stung him – our only casualty!

Of course nothing like this could happen these days with “Health and Safety at Work”, but I can vouch for the truth of the above reminiscence, those many years ago.

One afternoon, at Ally Pally, we had just finished a cookery program, and as Studio B was on air next, we were standby. We set up a position in the Studio for Mary Malcolm, just in case there was a breakdown, and we would have to make an apology. Having set up the shot of Mary in my viewfinder, I locked the camera off and we both went across to the cookery demonstration area, where the rest of the crew were tucking into some delicious freshly baked cakes. All of a sudden the floor manager, who was the only one wearing headphones shouted “Standby Studio – Mary – you have to apologise for a break-down.” Mary, with a mouthful of cake rushed back to the announcer position, closely followed by me. By the time I got to my camera and put on my cans, she had started. Luckily the shot was ok – she got back to her marks, and when I looked in my viewfinder there she was nice and centred, and in focus! She had made that announcement without a blink – with her mouth full of cake.

This story is a bit naughty, but never mind. One day, we learned that someone who was to give a talk in Studio B was unable to go on air – so a replacement had to be found quickly to fill the afternoon slot. We had a gentleman of the name David Wolfe-Murray, who was employed taking important visitors round the studios. I think he also wrote articles in newspapers under the pseudonym of “Fishhawk”. As he was an ornithologist, he was asked if he would give a twenty-minute talk on birds. With no rehearsal, and very little time to think what he was going to say, he agreed to go on-air live. So at three that afternoon he was in a small set, and I was the only cameraman. I can remember his opening words very clearly after all this time. Looking straight at the camera, and with a straight face he said “Good afternoon viewers. I’m going to talk to you today about tits. First of all I’ll tell you something about great tits”. At these words I had to fight an uncontrollable desire to burst out laughing!

Quite often, we would finish an afternoon transmission at about four o’clock, and the scene shifters would have to take away the set we had just used, and erect another one for the evening show. This would give us cameramen spare time as we probably wouldn’t be needed for rehearsal before about six o’clock. One of our cameramen, Mark Levi, was Chess and Bridge champion of the BBC, and he went to the trouble of teaching three of us to play bridge, so that he could play during these breaks. I was told an interesting story about Mark by another cameraman. Apparently Mark was operating camera two, and during rehearsals was playing a game of chess with one of the extras in the show. The extra had the chess set, and Mark’s tracker (dolly operator) would go across to the extra and tell him Mark’s move. The tracker would then come back to Mark and tell him the move that had just been made. So this was how they managed to play a game of chess during rehearsal, with the tracker going to and fro with moves. From what I have said, you will gather that Mark couldn’t see the board – he was remembering every move, and visualising the layout in his mind, as well as working on the rehearsal. Almost unbelievably, at one point Mark told the tracker that his opponent couldn’t make that move, because a piece was already on that square. The tracker went back, and sure enough it was the extra who had made a mistaken move, in spite of having the chess board in front of him – and Mark had spotted it. What a memory!

We had a senior cameraman of the name Michael Bond. One day he came into the studio and  told us that he had to make a difficult decision. He was writing children’s stories in his spare time, but he was thinking of doing it full time. He wasn’t sure – it was a great risk to give up a good job. We encouraged him, and said in effect “Go for it”. Michael did just that, and resigned his job soon after. The result was the birth of Paddington Bear!

told us that he had to make a difficult decision. He was writing children’s stories in his spare time, but he was thinking of doing it full time. He wasn’t sure – it was a great risk to give up a good job. We encouraged him, and said in effect “Go for it”. Michael did just that, and resigned his job soon after. The result was the birth of Paddington Bear!

There was something very free and easy about certain aspects of television in those early days. In October 1964 I worked on the serialisation of Alexander Dumas’s story The Count of Monte Cristo, as Lighting Director, directed by Peter Hammond, and the lead actor was Alan Badel. Other well known actors in it were Natasha Parry, Philip Madoc, Michael Gough and Rosalie Crutchley. Alan did not think highly of the script dialogue sometimes, and he would re-write it, and offer his suggestions to Peter. As far as I know, his ideas were always accepted, and I can remember going to an outside rehearsal one day, at a Boys Club in London, and Peter would say to me “ I wonder what changes to the script Alan will make today”.

We had a scene-shifter who was known as Robbie. He always chose to be the caption operator. Usually at the end of a program, the credit captions would go out. Two cameras, side by side, would be set up on the credit easels, and Robbie would be in the middle, wearing cans and changing the credit cards as the vision mixer switched between the two cameras. But Robbie had a brilliant sideline. He would sit by the caption stands during rehearsals, making different sized giraffes, some about eight inches high, up to about a foot. He would take several lengths of wire, and make a skeletal shape of a giraffe. He would then wind some cotton wool round the wire using cotton, to fill out the shape. He would then bind this into the final shape, using brown sticky tape usually used for sticking parcels. He now had the shape of a giraffe, and after painting some spots, and eyes on it, he would place the finished article on top of the caption easel. Sure enough, after a while some of the artists on the show would come up to Robbie to buy his giraffes. A nice little earner.

When we put on an evening play it would last perhaps an hour and a half. It was felt that this was too long for our viewers at home to sit through, so usually, about half way through we would put out an Interlude Caption, so that they could make a cup of tea. This would last perhaps a quarter of an hour, and it was useful for us, if a set change, or make-up change was necessary. A caption stand would be set up in front of a camera with a card saying “Interlude” on it. Studios are very crowded with artists, technicians, make-up ladies, scene-shifters, electricians, carpenters, plus a floor manager, and from experience you knew if you didn’t put up a barricade of chairs and ropes between the easel and your camera, someone was sure to walk across and be televised! There was usually quite a mêlée in the studio during these breaks, and I have known people, not realising, to move the chairs, or duck under the ropes, in order to get to the other side of the studio in the shortest distance!

When transmissions were about to finish every evening, we would put out a shot of Big Ben. Now of course we didn’t have a camera pointing at the real Big Ben – we had a model in the standby studio. The floor manager would be told when we had two minutes before  the clock would go on air. Then he would ask the half dozen people in the studio – who had the right time? After various different answers he would decide – and set the clock accordingly – plus two minutes. This was necessary because “Big Ben” had no mechanism – time stood still for our clock! Apart from the fact that very often we didn’t have the right time in the first place, sometimes our “two minutes” stretched to considerably more – timings of programmes (all live) wasn’t rocket science. If the preceding programme was someone talking to the camera it wasn’t always easy to get him or her to stop! (particularly if it was a politician!) Big Ben sometimes did not show the right time.

the clock would go on air. Then he would ask the half dozen people in the studio – who had the right time? After various different answers he would decide – and set the clock accordingly – plus two minutes. This was necessary because “Big Ben” had no mechanism – time stood still for our clock! Apart from the fact that very often we didn’t have the right time in the first place, sometimes our “two minutes” stretched to considerably more – timings of programmes (all live) wasn’t rocket science. If the preceding programme was someone talking to the camera it wasn’t always easy to get him or her to stop! (particularly if it was a politician!) Big Ben sometimes did not show the right time.

We had an electrician – Charlie Calfe, who, whenever he laughed (which was quite often) he would finish off with by snorting several times. Well Norman Wisdom was in the studio for an audition. Yes – this was a long time ago. He must have heard Charlie laughing, and finishing up with his snorts – because Norman adopted that sound, and it became one of his trademarks!

Just a quick mention of the world’s first half hour sitcom, “Pinwright’s Progress”. There were ten episodes, and they were transmitted live from Studio A at Alexandra Palace fortnightly in 1946/47. It ran for 30min. and our shift was lucky enough to work on all of them. James Hayter was the lead, and he was the proprietor of “Macgillygally’s Stores”. The show was directed by John Glyn-Jones, and rehearsals were a hoot. It was really really funny we had some great laughs during camera rehearsal. Of course Jimmy responded to the laughter, and gave it all he had got. Even when we went on air we had to work hard not to burst out laughing.

November 5th was always a noisy evening at Alexandra Palace, as many locals brought their fireworks to let off outside our studios. We nearly always had a serious play to put on, and as soon as our transmission started at 8pm we would hear a great barrage of bangers and rockets. The sound-proofing of our studios was virtually non-existent, which made life very difficult for our artists. We didn’t fare much better ourselves, because when we were going home afterwards, we would have fireworks thrown at us as we came out of the front door.

A quick mention of animals in the studio. Quite often we would have “the zoo man” George Cansdale in Studio B with a collection creatures to show to the viewers. Frequently there would be big birds of prey, and often they would fly off their perches, and stay up among all the lights. It usually took quite a bit of persuasion to get them down. Of course the animals would occasionally defecate rather ostentatiously, to the embarrassment of the presenter.

One final story – then I must move on. Soon after we started transmitting in 1946, producers including Mary Adams, wanted to know whether it was safe to make programmes about hypnotism, and so one day they set up an experimental session in Studio B. I worked in Studio A, but as we weren’t busy at that time, I wandered into B to see what would happen. I was highly sceptical about hypnotism at the time – I thought it was a hoax – or con. They had one camera on the hypnotist, and all the usual floor staff – sound crew and floor manager, plus a number of interested spectators. Upstairs, in the gallery were producers, vision mixer and other technical staff. The hypnotist, Peter Casson, looked straight at the camera and talked in a soft, soothing voice about you feeling sleepy. Four people became hypnotised – the cameraman, the vision-mixer, and two others. The result of the test was to show that televising programmes using hypnotism was just too dangerous. It was feared that some viewers at home might become hypnotised and not be brought out of that state. Later he performed another experiment. It seems impossible, but I am pretty sure I remember a young female announcer, probably Gillian Webb, being hypnotised, and was made to stretch out, straight as a board, facing the ceiling, with her feet resting on one chair back, and another chair back supporting her under her neck – no support in the middle. She stayed like that for some seconds, and apparently with no ill-effects afterwards!

I can’t remember why, but our S.Tel.E. Mr Whiting decided that camera crew members would also help out as reliefs’ manning the PBX desk. Just above “A” racks area was a small room housing the local telephone exchange desk. It consisted of a number of cords that were used to connect two sources together. A caller would ask to be connected to another technical area, and the operator would use a cord to connect the two. When the call was finished, the cord would be disconnected. Bimbi Harris instructed me one day how to operate the equipment, and left me to it. Things went well for a while, but as time approached for the afternoon transmission, panic set in. More and more calls were coming in, and I was running out of connecting cords. I didn’t always have time to check if a particular call had finished – I needed a cord so I just pulled it out and used it for the next call! Utter chaos ensued, with many irate and frustrated users. Needless to say, Mr Whiting did not ask me to operate the desk again.

In October 1949 I applied for, and got the post of Cameraman on the Outside Broadcast Unit, based in Wembley. It was a very enjoyable time, but physically hard work. At first I worked on the unit that was equipped with EMI C.P.S. cameras – and they were very heavy. It took two of us to carry one camera in its cradle, and we usually rigged four. We did many OBs from Twickenham, covering rugger matches, and moving all that heavy equipment from ground level up to the top of the stands, where our cameras were to be positioned was very tiring.

On one occasion we had an O.B. from the Kursaal, a huge pleasure and amusement park, and fun fair at Southend, with Richard Dimbleby (what a gentleman!). After our transmission, Richard and the whole team had free rides on anything in the fair. A great night!

In 1950 (27 August) I was in Calais (France) sending the first television pictures across the Channel (Calais En Fete). It was a two-hour programme broadcast live from Calais to mark the centenary of the first message sent by submarine telegraph cable from England to France. Viewers were able to watch the town of Calais “en fete”, with a torchlight procession, dancing and a firework display all taking place in the Place de l’Hotel de Ville. Presenters Richard Dimbleby and Alan Adair gave commentaries on the festivities and interviewed local personalities in front of the cameras. What a time we had!

In 1950 (27 August) I was in Calais (France) sending the first television pictures across the Channel (Calais En Fete). It was a two-hour programme broadcast live from Calais to mark the centenary of the first message sent by submarine telegraph cable from England to France. Viewers were able to watch the town of Calais “en fete”, with a torchlight procession, dancing and a firework display all taking place in the Place de l’Hotel de Ville. Presenters Richard Dimbleby and Alan Adair gave commentaries on the festivities and interviewed local personalities in front of the cameras. What a time we had!

In March 1951 I was on the Thames in a launch covering The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race – and saw Oxford sinking in high winds and choppy water. It was re-run a couple of days later – and Cambridge won.

In May 1951 I was with the unit at “The Festival of Britain” for a week. It was held at the South Bank site near Waterloo Station, and again we had a fascinating time. There was The Dome of Discovery, the Royal Festival Hall, and many, many more things to see. I must mention one true story about covering The Festival of Britain. There was a very tall object called “The Skylon”. It looked l ike a huge cigar, its base suspended 40ft, from the ground, over 300ft high. I had a heavy cps camera on a 3ft. rostrum (with no safety rails around it), and my job was to start my shot on its base and pan right to the top. As the normal camera mounting wouldn’t permit panning up so steeply, I had a piece of equipment beneath the camera called a 45 degree up pan wedge, which allowed the camera, mounted on an “iron man”, to pan up a further 45 degrees. In this position the camera was pointing almost vertically. We were rehearsing just before transmission, and my shot was set up on the base of the Skylon, and I had to pan up to the very top. It started out well. But just as I was reaching the top, the clips holding the camera to the wedge gave way, due to the weight. The camera left its mounting, and as I was right behind it, it pushed me back – off the rostrum, on to the grass below. Unhurt, but a little surprised, I picked myself up climbed back on to the rostrum, and put my headphones back on. The camera was resting on the rostrum’s wooden base, and the first thing I heard on my cans was the director, telling me to pan up! Immediately afterwards my racks engineer asked me to check focus. Amazingly that camera had fallen some four feet, and was still giving a perfectly good picture. No-one would believe me when I told them what had happened.

ike a huge cigar, its base suspended 40ft, from the ground, over 300ft high. I had a heavy cps camera on a 3ft. rostrum (with no safety rails around it), and my job was to start my shot on its base and pan right to the top. As the normal camera mounting wouldn’t permit panning up so steeply, I had a piece of equipment beneath the camera called a 45 degree up pan wedge, which allowed the camera, mounted on an “iron man”, to pan up a further 45 degrees. In this position the camera was pointing almost vertically. We were rehearsing just before transmission, and my shot was set up on the base of the Skylon, and I had to pan up to the very top. It started out well. But just as I was reaching the top, the clips holding the camera to the wedge gave way, due to the weight. The camera left its mounting, and as I was right behind it, it pushed me back – off the rostrum, on to the grass below. Unhurt, but a little surprised, I picked myself up climbed back on to the rostrum, and put my headphones back on. The camera was resting on the rostrum’s wooden base, and the first thing I heard on my cans was the director, telling me to pan up! Immediately afterwards my racks engineer asked me to check focus. Amazingly that camera had fallen some four feet, and was still giving a perfectly good picture. No-one would believe me when I told them what had happened.

In December 1953 I applied for and obtained promotion to Senior Cameraman, and returned to London Television Studios. On returning I had to resume work at Lime Grove. I lived in Weybridge, Surrey and travelled to Shepherds Bush on an ordinary bicycle that had the rear wheel replaced with a “motorized wheel”, called a “Cyclemaster”. This would chug along at about twelve to fifteen miles an hour, but do about three hundred miles to the gallon! There was no protection from the cold on the bike, and in the winter of 1952 coming back from work, I was literally frozen stiff, after a journey of about fifteen miles.

In December 1953 – just after Christmas, I was promoted to Senior Cameraman in charge of Crew 6 then in February 1954 I was put on to a Lighting Trainee Course at Evesham, and by February 1955 I had passed a Selection Board for the post of Television Lighting Supervisor. By about 1960 I was earning enough to be able to afford a car – and we bought a Ford Popular – brand-new for £250.

I have written quite a lot about my experiences, working on cameras, and yet the vast majority of my Television life was devoted to the lighting element of productions. There was a big difference in the two jobs. As a cameraman, or even a senior cameraman I could always feel part of a team, and I was always told what was required by the Director. As a Lighting Director I was solely responsible for the look of a production, and it was my ideas and concept that the viewer would see. For this reason a Director was allowed to choose who he or she wanted to light their production. It was very necessary that they both worked closely so that the style of the pictures fitted the production. Lighting Directors tended to specialise in the type of production that suited them best – either Light Entertainment or Drama. Although I worked in many Light Entertainment shows – such as Vera Lynn and Top of the Pops, after a while I became better known with the Drama Directors. This tended to happen with Crews, and Sound Supervisors as well, and so quite often on big productions I would find myself working with the same people, which was a big advantage. Quite often, to get the most dynamic and interesting lighting, it requires close co-operation with Sound Supervisor and Cameramen. Unwanted shadows are constant problems that have to be dealt with, and working with a co-operative Sound Supervisor who could help out to avoid boom shadows, and Cameramen who could likewise avoid camera- shadows, when taking close-ups, was a great help. Of course sometimes actors shadow each other, but those experienced in film making would automatically know how to avoid these. Sometimes it would be necessary to have a tactful word with an artist, to help them deal with the problem.

When I first started Lighting I worked on many Children’s serials. After a few years I was working mainly on Drama Series, and finally, in the last years of my career, I worked on major one-off plays. For many television viewers watching a play their only concern is the story. It is very unlikely that they will have any inkling of the huge number of people involved for many weeks with the making of that drama. They can see the artists, but in fact they are just a small part of the army of workers who have contributed their skills to make it…..

A producer has his idea for a production accepted by the Head of Drama, and he or she commissions a writer to adapt the story for television. At the same time a Director is chosen to be responsible for the artistic interpretation of the work. Producer and Director then set about the task of casting artists for the various parts, auditioning if necessary. Next the Director will choose his production team – he or she will need Scenic Designer, Costume Designer, Make Up Supervisor, Sound Supervisor, Lighting Director, Technical Manager and a Camera Crew. Each of these Supervisors and Designers has a team of assistants to help with the various problems. It will be necessary to book a Television Studio, and the technical equipment that will be needed for the production. An Outside Rehearsal Room – probably a Church Hall or Boys Club will be booked. Outside rehearsals can then start, probably about six weeks before recording. Meanwhile scripts will be printed for all concerned, and the Scenic Workshop will start building the sets once the Designer has drawn the necessary plans. Costume Designer will be busy organising the making or hiring of the artists clothes, and Make Up will be dealing with wigs and any special make-up requirements . Special Effects Department will be involved if any explosions are needed, and the armourer if any fire-arms or weapons are required. Any unusual technical requirements will be discussed and dealt with by the Technical Manager.

So, how does one go about lighting a television production? Well. I will take as an example a typical play – say Michael Wearing’s production of “Stars of The Roller State Disco” with a running time of 90 minutes. This was one of the Play for Today series, and had a cast of fifty, all unknown, except Gillian Taylforth, who was taking quite a small part. She is probably better known as Kathy Mitchell of Eastenders. It was directed by Alan Clarke, a very demanding man I had never worked with before. We made the play in TC1, the biggest studio in Television Centre (32.5m x 30.5m x 13.7m high), being allocated five studio days to complete it. We used a technique called rehearse/record where we would rehearse a scene, and then immediately afterwards record it. The more usual method of working was to slowly work through the whole play, have a dress rehearsal and then record the whole drama. That way, it was better for the artists. These recordings weren’t necessarily in story order, but shooting a number of scenes in an area, or part of the set. These recordings would be later edited into story order. We were scheduled originally to make this production in the studio between 26th and 30th March 1984, but due to Industrial Action it was lost. We started the remount on Wednesday 30 May 1984, working each day from nine in the morning until ten o’clock at night, for five consecutive days. It was a somewhat surreal play, action taking place in a futuristic State run roller skating rink and adjoining rooms, provided to help teenage delinquents integrate into society. They live, sleep and eat in this environment, and exercise by roller-skating. We followed the lives of a number of the inmates, and I can best describe it as a squalid look at the existence of some of the most deprived youngsters, one of whom has become so institutionalised that he cannot bring himself to leave, in spite of being offered a very good job. At the end of the play he commits suicide.

I would have been allocated to this production about three months before it came into the studio, and would have received a script, and sometime later a floor plan of set layout, and elevation drawings of the sets. There would have been an initial meeting with Alan Clarke and the Set Designer David Hitchcock. Additionally at this meeting would be the Technical Manager Jeff Jeffery and Sound Supervisor Chick Anthony. Alan would outline to all of us how he wanted the production to look and sound. Basically it should be very real, and have the feeling of an institution, but the climax of the play – the Roller Disco, should be atmospheric and feel like a happy event, for the youngsters to enjoy. Technically as well as using the standard five cameras, we were to use an additional camera fitted with its own recorder, hand held. It would transmit its picture by wireless, and be picked up in the control room, so that we could all see the result. A lot of video games and television monitors were to be used. At one point in the play, one of the inmates has to squirt a hose at a picture monitor, and Jeff had to work out how this could be done safely.

The whole of the floor area of TC1 was to be used. The major part was taken up with an oval shaped roller skating rink, in the form of a ring. Inside the ring was the dormitory area, and this was where the hand held camera was to be used – the standard cameras could not get to this area because of the circling skaters. Off the rink were about a dozen small rooms, where the inmates were supposed to learn useful skills, and amuse themselves. The Technical Manager would make notes about technical requirements, and advise and help Alan on any problems. Any parts of the set design that I didn’t understand, or heights of some sets were discussed with David Hitchcock, Set Designer. I said that I would like to light some of the smaller sets with hanging practical lights, and asked him to provide some of those conical glass shades that were deep green on the outside that are seen in workshops. This would provide a harsh overhead lighting that would suit the drama. Finally I tell Alan I will need an allocation of money to hire disco equipment and additional light sources.

This concluded the initial planning meeting, although the director or the set designer may wish to discuss further points with me before the production comes into the studio. About a fortnight before this, I will go over to the Set Construction area in Scenic Services Workshop, to see how the sets are looking.

After this planning meeting, and before studio rehearsals I will be allocated two studio productions each week. They may be simple productions like Panorama or Sportsview requiring little planning. There may be however another big production in the pipeline requiring a script read, understanding floor plans and a planning meeting.

I will then re-read the Roller Disco script, going through it in detail, making notes of the different lighting conditions. The play begins with an early morning scene, with the youngsters waking up and getting out of bed. This should be dark and spooky, and the opening credits will run over this. One youngster is already skating around the ring. One by one the lights come on in different rooms, and the action begins. Some areas have to be brightly lit, and others quite dark and foreboding. I decided to make the outside world, seen through a door in the complex to appear very bright, to heighten the feeling of despair and gloom inside. Finally, I will have to alter the appearance of the skating area for the disco scene.

About three weeks before we are due in the studio (18th May), I will go along to a preliminary rehearsal. This was at the BBC’s North Acton Rehearsal Block in Wales Farm Road, and they would do a complete run for me. Quite a bit of the action and dialogue takes place whilst our artists are roller-skating, so this leads to difficulties, as there are no facilities to do this. Sets are marked out with tape on the rehearsal room floor, and by looking at the floor plan, I can see where any action is taking place. The rehearsal room is a lot smaller than the studio, so the outlines of the sets overlap. By using different coloured tape for overlapping sets it is possible to see them more clearly. Before I leave, I pick up a scale model of the set, made in card, so that I have a three-dimensional view of the set, showing the heights and the shape. In the next week, I will mull over a lighting plot. This will show the position and power of every lamp that I want to use. As there is to be a “disco” scene I will have to hire a number of the type of effects lights used on Top of the Pops. Basically I want to light the skating rink with spotlights straight down. The skating area is an oval ring about three metres wide, and the skaters go round and round, almost continuously. This will need forty-five spots, all hired. I realised early on that I had a power problem. To light the whole of the studio my plot showed that I would want more power than was available, and bring the power breakers out. In total I planned to use fourteen ten kilowatt lamps (140Kw), two hundred five kilowatt lamps (1000kw), fifty one kilowatt (50 kw), and in addition, a lot of practicals, and effects lights. This came to something in excess of 1220 kw. The maximum power rating of the studio was 750 kw., and I also had to consider whether the ventilation and cooling system could cope with such a huge load. This meant minimising the number of lights in use at any one time. Studio lighting is controlled by a lighting console, and memories can be set up by my assistant, to provide the lights required for a particular scene. The dimmer level of every light source can also be memorised. I will also be thinking of the various colour gels to be used in certain lights, for effects. For instance, for the opening scene before lights come up, I want the rooms round the rink to be dimly seen with red light. For the disco scene I want a number of bright colours around the rink.

Four days before we are scheduled to be in the studio (24 May) we have the Technical Run. This rehearsal at North Acton is attended by Jeff and myself, and is our last chance to ask questions, and clarify exactly what we intend to do.

After this I have to finalise my lighting plot and patching sheet (giving numbers to every light source to be used). The studio has 256 motorised lighting hoists overhead, each one having a Berkey dual source lantern on it. My plot will show which of these are to be used, and in what mode, and the direction in which the light is to point. Additional lights will be rigged on these bars to my requirements. After this I make seven photo-copies of the plot – two for electricians, one showing coloured gels, one for me, one for my assistant, and one to go in to my in-tray for emergencies! In addition I make a list of memories, prepare a plot showing which lamps have coloured gels, and order hired equipment. These tasks will take me through the afternoon and most of the next day. By six o’clock on Friday (25th) the Foreman Electrician will expect my completed plot, as he has an electrician crew coming on duty at 11pm that night to rig my plot. The studio floor will be empty, and they will drop all the motorised hoists to ground level, and rig and adjust the required lanterns. Afterwards all the hoists will be taken up to approximately 25ft., leaving the floor area free. The next morning (26th) the Scenic Services crew will come in and build the sets, finishing hopefully by evening. I am allocated Sunday 27th as a Fine Light day. I start at nine in the morning and by five I am finished. Whilst this is going on Workshop Electricians will be wiring up the many practicals to be used, and also making the video games work. The Set Designer will be “dressing” the sets, and putting finishing touches to each one. We all have to beware areas that have floor paint still wet – it’s very slippery!

I will be in the next morning (28th) at nine o’clock to brief my two assistants, Chris Townsend, Vision Supervisor, and Chris Watts, Vision Operator. My Vision Supervisor will look after the operation of the Lighting Console, and largely oversee the light balance, to achieve the most interesting pictures. He is a top-notch operator – the best! The vision operator will look after the exposure, black level and the brightness of all cameras, a very important job. I will also get the channel numbers of all the practicals from my charge-hand electrician, so that we have total control.

Today (Wednesday) is the first day of rehearsal, and the technical staff (cameras and sound) will be busy at this time rigging technical equipment. Make-up and wardrobe, design assistants, floor manager, electricians, carpenters and many more will be busy preparing for the start of rehearsals.

At eleven o’clock precisely, the floor manager calls for silence – stop all work – and rehearsals start. My two Chris’s and I are up in our Control Room, looking at the first pictures. We have two hours of rehearsal, and then at one o’clock break for lunch. From two ‘til two thirty the cameras are lined up, and rehearse/record commences at two thirty, and stopping at six o’clock. We break for an hour’s meal, line up cameras again for half an hour, then rehearse/record from half past seven until ten o’clock – when we can all go home!

We carry on this routine for the next four days, and hopefully by ten o’clock Sunday night we have got everything in the can! I will have been kept busy making any minor adjustments to the lights, and guiding my two assistants as to how I want the pictures to look.

When we have got the last bit recorded, there is a tremendous feeling of euphoria. We have worked as a team for the production for the last five days, and we all feel that we have successfully overcome problems together. It takes quite a lot of co-operation, a lot of give and take between us all. But every-one connected with the production, whether artist, technician, production staff, designer, make-up, wardrobe, scene hand or electrician has played a part in making the play a success. It is at moments like this I realise that I have the best job in the world!