From Chris Cory

In August 1960 I was assigned to the Television Recording Section at Lime Grove Television Studios as an operations and maintenance technician. I was only concerned with Telecine; the means of broadcasting film. The equipment was known by a numbering system starting at TK 1. We had fifteen machines at Lime Grove.

Please bear in mind that the TV standard was 405 lines and colour wasn’t generally available until 1967. Also broadcasting hours in 1960 were limited to 55 hours per week!

We had a control room with a desk holding four of the ubiquitous 2780 14” PYE monitors for previewing telecine machines and a 17” Cintel for monitoring our line out to CAR. Routing to CAR or individual studios was by video ‘MUSA’ patch leads and a standard Post Office audio jack field. An experimental system employing telephone ‘Uniselectors’ had been installed and used but wasn’t considered to be reliable enough on its own, so was always over-plugged. The control room space was half-filled with racks of distribution amplifiers – all valve of course.

Film transmission on TV was; and still is; in two formats; 35mm and 16mm. We didn’t have facilities to broadcast amateur film formats. Sound is typically carried as a photographic stripe squeezed between one side of the image and sprocket holes. Hence a slight misalignment of the sound head would produce a terrible buzz. This is known as ‘comopt’ and could be variable density or variable area. Sound is reproduced by focussing a very narrow line of bright light through the sound track, onto a photocell.

This representation of 35mm comopt film has a variable area sound track.

The upper frequency response was limited to around 6 kHz. Distortion and noise were pretty diabolical by today’s standards. When films were having their sound dubbed on, a system of ‘ground noise reduction’ was used; very similar to an early Dolby system. It suppressed noise when there was no intentional sound but did introduce some distortion. 35mm films were usually comopt, whereas 16mm could be comopt, commag or sepmag.

35mm film is packaged as 1k, 2k, or 3k spools and runs at 98 feet per minute. It was transported in metal tins, tightly wound on a 2” diameter plastic centre with a moulded keyway. Before transmission this had to be wound onto a heavy steel spool with cheeks and a centre diameter of around four inches. We used spools that separated into two halves and accepted the plastic transport centre. This protected the film whilst we wound it manually onto its playback spool.

Therefore it was normally shipped tail-out. At TVC we were supplied with the luxury of a horizontal bench that wound film by an electric motor. The large centre alleviated most of the torque variation as the film was run. Tension was maintained by a friction brake, so increased as the film unwound.

The sound was largely impervious to torque variations, as the mechanism had a heavy flywheel capstan drive buffered by a loop of slack film. Due to the feed spool friction braking, our machines could not be run in reverse.

35mm film gave approx. 10, 20 or 30 minutes running time. 16mm film would be supplied to us as 30 or 60 minute spools. Two mechanisms are therefore required to provide a continuous viewing of feature films. Changeover was achieved exactly the same as in the cinema, i.e. by watching for a cue dot in the top right hand corner of the picture. The 35mm machines took 8 seconds to achieve a stable running speed, so a length of leader film was always present, with numbers printed to indicate the correct start point. TK cues from the production suite would allow for this. When providing film inserts to a studio, we would ’park’ the TK at 10 on the film leader. In a cinema projector this would have given a 10 second run-up time but our machines were quicker.

Cinemas show film at 24 frames per second; TV displays pictures at 25 fps in the UK. To complicate matters, the TV picture is interlaced, that is, each frame is scanned twice at 50Hz with a half line offset. Each of these scans is called a field, one odd, one even. Interlaced scanning requires half the bandwidth of progressive and produces a less obvious flicker to the average human eye.

Cinema projectors use a bright light to project a complete image on a screen and each frame is presented whilst stationary in the gate – intermittent motion. A shutter obscures the light path whilst the film is pulled into position and persistence of vision in the human eye delivers what appears to be a picture without any interruption.

TV scanning presents a problem with film because the vertical scan flyback time (approx. 1mS) is much shorter than the time taken by a cinema projector mechanism to present the next image.

Therefore, in the majority of telecines, the film runs continuously and various methods were employed to arrest the captured image.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

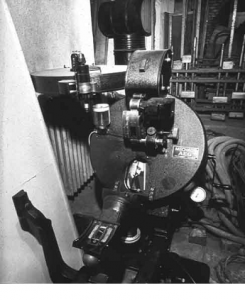

This was the German Mechau continuous motion film projector; pressed into service as the first telecine. My thanks to the Tech Ops website for the above picture.

The light source was a very bright and finely-focussed CRT that scanned the film with an interlaced 4:3 raster. This is known as the flying spot system, as pioneered by Baird. All of the telecines were flying spot in the 1960s. The large drum assembly houses a disc comprised of many segments that were pivoted and tilted by cams as the disc rotated. After passing through the film, the modulated spot was now collimated onto a photo multiplier cell; see the photo below.

The effect was to arrest the motion of the film image as presented to the scanning CRT so that a full frame was illuminated by the flying spot. A still frame could be viewed but a separate flying spot slide scanner was provided to produce a far superior image when required. This was switched into the same electronics as used by the Mechau. We had three of these Mechaus at Lime Grove and they were used primarily to run opening titles for many programmes such as “This Is Your Life”. They were numbered TK7 ,8, and 9.

One machine was on permanent standby with a short ‘filler’ film: “Messing about in Boats” and “The Potter’s Wheel” for example. In those days programmes other than film were all live and had to start at the published time. A fourth machine was located at BBC Riverside studios, to run opening titles and filmed outdoor scenes for “Dixon of Dock Green”.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

A photomultiplier cell as used in all our TKs in the 1960s.

These were extremely sensitive devices, developed for nuclear research projects, where detection of single photons was desirable. A single photon; striking the photo-sensitive window on the right of the picture; would release an electron or two. The metal structure; visible inside the glass body; is a series of dynodes, all supplied with a positive voltage. This voltage was supplied from a ladder of resistors so that only tens of volts are on the dynode nearest the photocathode; whereas at the output end; there was 1kV. As each dynode attracts incoming electrons, secondary emission produces more, multiplying by several thousand in total.

The Mechaus were superseded by twin-lens systems built by EMI. Naturally we needed a minimum of two. They were numbered TK1 and 2.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

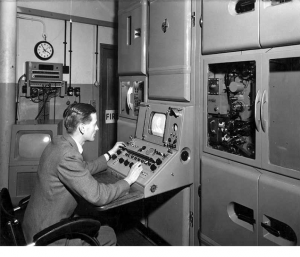

This is TK2 being operated by Bill Tucker who was shift one supervisor.

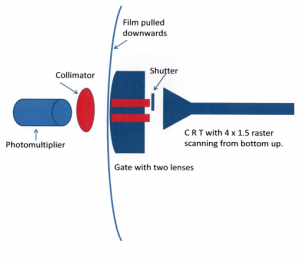

These also employed a very bright and finely-focussed CRT, but scanned from bottom to top at 4 x 1.5 aspect ratio whilst the film travelled past downwards. The film gate had a second lens, exposed to the CRT whilst the first was obscured by a shutter. The same frame of the film was thus scanned twice. Due to offset of the lenses, this meant that an interlaced TV picture resulted.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

You can see that these were massive machines but still only capable of running a maximum 20 minute reel. (35mm)The 35mm mechanism is to the right of the operator. The panel above his head was opened to access the scanning tube that was fitted face-down and had an operating voltage of 28kV. Beneath the scanning tube was a mirror that could be flipped over to direct the flying spot to a 16mm mechanism that can be seen to the operator’s left. The 16mm unit was used for “Match of the Day”. This film arrived fresh from being developed and of course, negative. Electronic alignment of the machine in preparation for this most important programme, took more than an hour, using a Cossor oscilloscope.

Rank Cintel (formerly Baird) developed a much improved version of the 35mm twin lens flying spot telecine.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

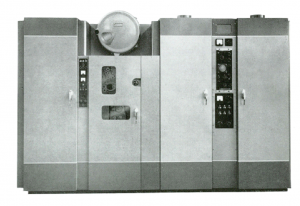

This is TK5. TKs 3 and 4 were identical.

At Lime Grove we had a pair; TK3 and TK4, plus TK5 as a spare. These were used every day and carried a large proportion of the programme output. All 35mm feature films and documentaries were transmitted from the two Cintel machines. If you recall Cliff Michelmore and the “Tonight” programme, all the inputs from Fyffe Robertson and Alan Whicker ran on these. In addition, filmed crime series like “Maigret”, plus BBC and imported film recordings such as “The Perry Como Show” kept them busy.

The twin lens machines couldn’t display a still frame, so we used a long loop of test card C film for machine alignment.

The 10 on the leader appeared something like this on the Studio monitors:

Streaking from highlights occurs in flying spot telecines due to afterglow of the scanning tube. Ideally the CRT should scan the film frame as a precise focussed spot. However, CRT phosphors don’t stop glowing immediately after the electron beam moves away. Hence a comet-tail streak appears to the right of any film highlight areas. Correction for this was part of our alignment procedure.

On the right of the opened-up machine above is a pair of spool carriers that could take reels of 35mm magnetic tape. It was the same mechanical spec. as film but was prohibitively expensive and I never saw it used. However ‘Sepmag’; as this would have been called, was almost universally supplied with 16mm film, when it had been produced in-house. It brought the advantage of better quality sound than was possible with 16mm optical. Separate tape players made by ‘Westrex’ were synchronised to the telecine at the start of a programme. Here again the standard was 16mm just like the film stock.

At the top can be seen a 2k spool onto which the film would be loaded for play out. Note the orange tint to the open door, shielding the optical sound system from the ambient light even though we operated in subdued light whilst on air.

The picture quality from these Cintel telecines was superior to most of the TV cameras of the day. Even in 1968, when I left for pastures new, camera pictures still lacked the crispness and low noise produced by the flying spot system. In fact, monitoring a Cintel 625 line colour machine in RGB, displayed pictures better than the so-called 720P HD of today. Although the “Perry Mason “series was broadcast in black and white, we could monitor the colour output from the machine locally. “The High Chaparral” was one of the first 35mm film series broadcast in colour and the pictures were outstanding. Colour was only broadcast from the new TVC facility.

The EMI and Mechau machines were not consigned to the scrap heap until 1966, but kept busy as programme requirements grew each year.

Alignment of these Lime Grove Cintels was a doddle, needing infrequent adjustment of streak correction and focus. The scanner tubes could be so well matched that a changeover from one machine to the other was not visible.

A further Cintel 35mm twin lens machine, TK6, was used for colour test transmissions employing the new 625 line PAL system. There was a colour slide scanner as well. We ran cartoon compilations and a series of Shell short features including one covering the building of the Kariba dam.

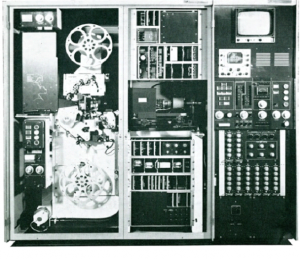

TVC was kitted-out with telecine machines that were basically the same as TK6, as shown below.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

The addition of colour required an extra two channels of video processing, and valve technology was still used throughout, making the equipment very bulky. By 1968 we were sourcing spare SP61 valves from the various government surplus stores still trading at the time. Alignment of these machines would take an hour prior to transmission. They could handle 3k film reels.

Just imagine the weight one had to lift onto the feed spool spindle just above head height!

A growing amount of TV programming arrived in 16mm format. Nearly all of the popular series like “The Lone Ranger”, plus many of the children’s animated films like “Magic Roundabout”. Also on 16mm were documentaries such as “Your life in Their Hands”, crime dramas like “Tim Fraser” and many other popular series produced by the BBC film unit.

We had four dedicated 16mm Cintel machines for these at Lime Grove: TK12, 13, 14 and 15.

Later, four were installed at TVC. None of them were twin lens.

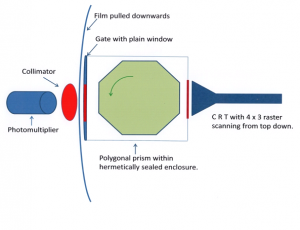

The original Mechau used a tilting mirror means of arresting the film frame whilst being scanned. It wasn’t perfect for the job by any means, producing noisy, flickering pictures.

Cintel therefore used a polygonal prism that rotated synchronously between the scanning tube and the film. These machines produced very acceptable pictures and were easy to use and maintain.

Each facet corresponds to one film frame and, with the motions of the polygon and film synchronised, the 4:3 interlaced image of the scanning raster follows the film exactly.

The only drawback was some loss of light and added flare to the image. Coupled with the fact that the image was a lot smaller than 35mm, pictures were noticeably poorer than the big 35mm machines. These machines, however, could display a still frame. Films made in-house usually had a separate magnetic (sepmag) sound track that was played on a Westrex machine synchronised to the TK. We could also play films with a magnetic track in place of the comopt. This was commag, though rarely encountered.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

Cintel went on to develop an improved machine for 16mm. This used a novel twin claw system that was capable of pulling the film into position ready for scanning, in the time taken by the flying spot flyback. Naturally it was called the rapid pull-down machine. These were being installed at Television Centre as I left in 1968. As the optical system was minimal, the pictures were much less noisy and had negligible flare.

(Click on the picture below to see larger version:

use your Browser’s BACK button to return to this page)

This picture is of such a machine that is not only rapid pull-down but 625 line colour and behold: not a valve in sight! The sepmag sound reproducer would have been in a separate rack to the left.

Photos of Cintel machines courtesy of Rank Cintel.

© 2015 C N Cory